Walk down a British high street today and you might see them: red crosses fluttering from lampposts, draped from balconies, or fixed proudly to car bonnets.

For some, the St George’s Cross is nothing more than the England flag, a symbol of sporting pride or local identity.

For others, it sparks unease, recalling decades in which far-right groups marched beneath it, shouting exclusionary slogans about who does and does not belong in Britain.

This tension over flags is not new. History is filled with symbols that were once benign but later became political battlegrounds.

Few examples are more striking than the swastika — an ancient emblem of good fortune used for centuries across Asia and Europe, until the Nazis transformed it into one of the most hated and feared symbols in human history.

Today, as grassroots campaigns such as Operation Raise the Colours call on people across England to fly the St George’s Cross, Britain faces a question with deep historical resonance: when does patriotism tip into nationalism?

And what lessons can be drawn from Nazi Germany about how symbols can unite or divide?

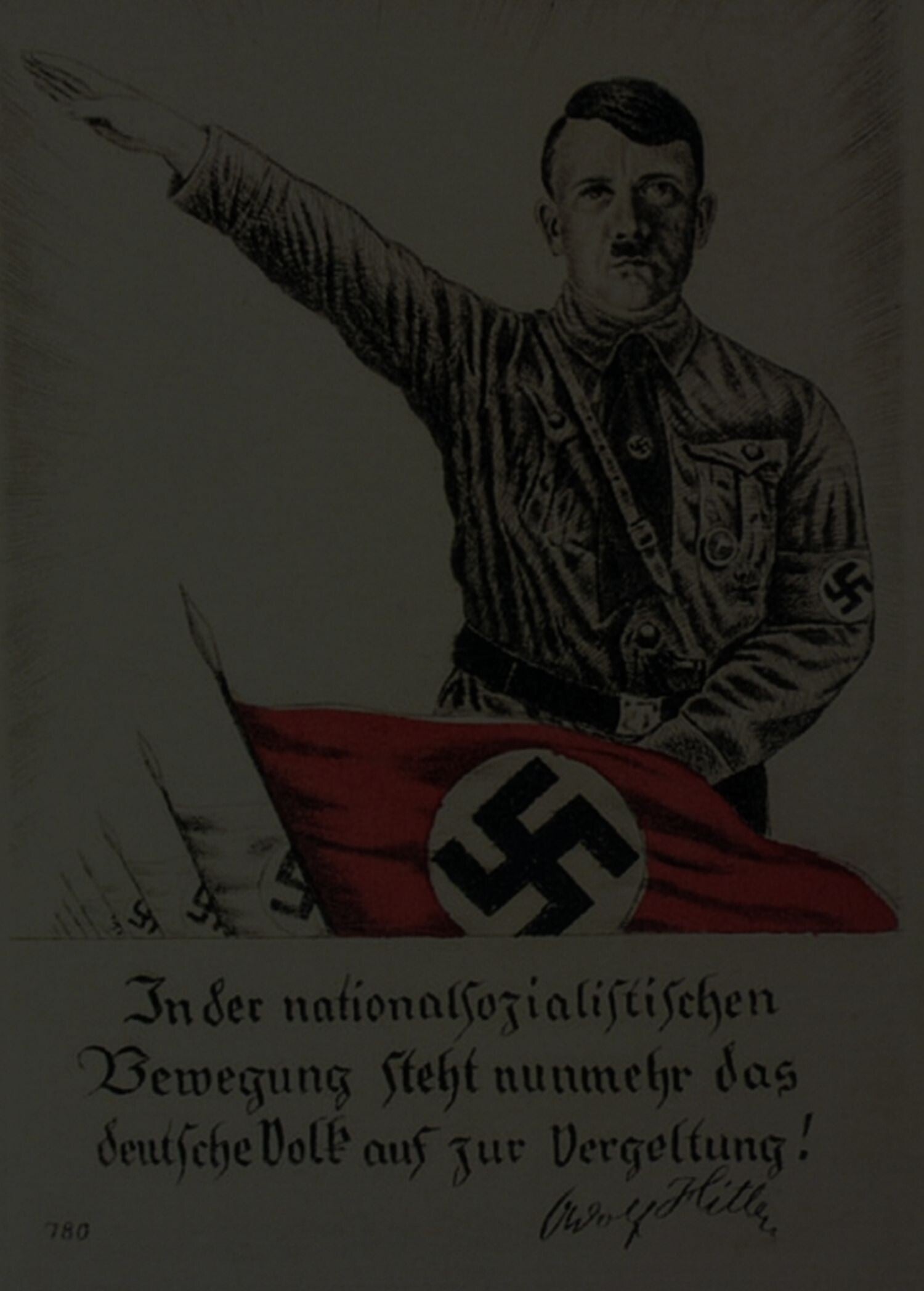

The Swastika: From Good Luck Charm to Weapon of Terror

Long before Adolf Hitler scrawled his ideas about race and power in Mein Kampf, the swastika was a symbol found on pottery, coins, and temples from India to Scandinavia.

In Hinduism and Buddhism, it remains a sacred sign of prosperity and good fortune.

Early 20th-century Europe even adopted it casually: swastikas adorned postcards, uniforms, and even the logo of the Finnish Air Force.

But in the early 1920s, the newly formed National Socialist German Workers’ Party (the Nazis) adopted the swastika as their official emblem.

Hitler himself wrote that the design was chosen to represent the “victory of the Aryan man” and to project racial identity as a unifying, militant force.

By 1935, when Hitler consolidated his dictatorship, the swastika was not just the party emblem — it was the German national flag. Other flags were outlawed.

The swastika fluttered from every government building, every school, every street corner.

It became impossible to walk through a German town without being enveloped by its message: loyalty to the Führer, exclusion of Jews and minorities, and a vision of racial destiny.

What had once been a symbol of cultural exchange was now a weapon of terror.

Its omnipresence was not an accident: the Nazis understood the psychological power of symbols to normalise ideology, erase dissent, and blur the line between personal pride and political obedience.

Patriotism or Nationalism? Drawing the Line

The Nazis’ use of the swastika offers a sharp lesson in how patriotism can morph into nationalism. Patriotism, at its best, is love of one’s country, pride in its culture, and a desire to see it flourish.

It can be warm, inclusive, and celebratory — think of cheering on the England football team or celebrating the NHS as a source of national pride.

Nationalism, however, twists pride into exclusivity. It is not just about loving one’s own country, but about defining who counts as part of it — and who does not.

Nationalism often depends on an enemy, an “other” to exclude, blame, or attack. When a symbol of patriotism becomes a weapon to distinguish insiders from outsiders, it moves into nationalist territory.

That was the fate of the swastika in Nazi Germany. And that is the risk some see today in the contested politics of the St George’s Cross.

The St George’s Cross: A Flag with a Fractured Legacy

The St George’s Cross — a simple red cross on a white field — has been England’s flag for centuries, originally flown by crusaders in the Middle Ages.

It has been associated with monarchy, with empire, and with the English nation itself. Yet its meaning has rarely been stable.

In the late 20th century, particularly in the 1970s and 1980s, the flag became closely tied to football hooliganism and far-right movements such as the National Front and later the British National Party (BNP).

Marches in London and elsewhere saw extremists wrapping themselves in the St George’s Cross while chanting racist slogans, turning the flag into a symbol of exclusion for many minority communities.

Even today, groups such as Britain First and figures like Tommy Robinson have used the flag in their campaigns, presenting themselves as defenders of “Englishness” against immigration and multiculturalism.

For many Britons of colour or immigrant heritage, the St George’s Cross has too often been the backdrop to intimidation and hostility.

At the same time, millions of ordinary people see it differently. For them, flying the St George’s Cross is no more sinister than flying the Saltire in Scotland or the Welsh Dragon in Cardiff.

During international football tournaments, high streets and pubs are decked out with flags in a spirit of celebration and unity.

This tension — between pride and intimidation, unity and exclusion — lies at the heart of the current campaign to put St George’s Crosses on lampposts and roundabouts across the country.

Operation Raise the Colours: Grassroots Pride or Political Battleground?

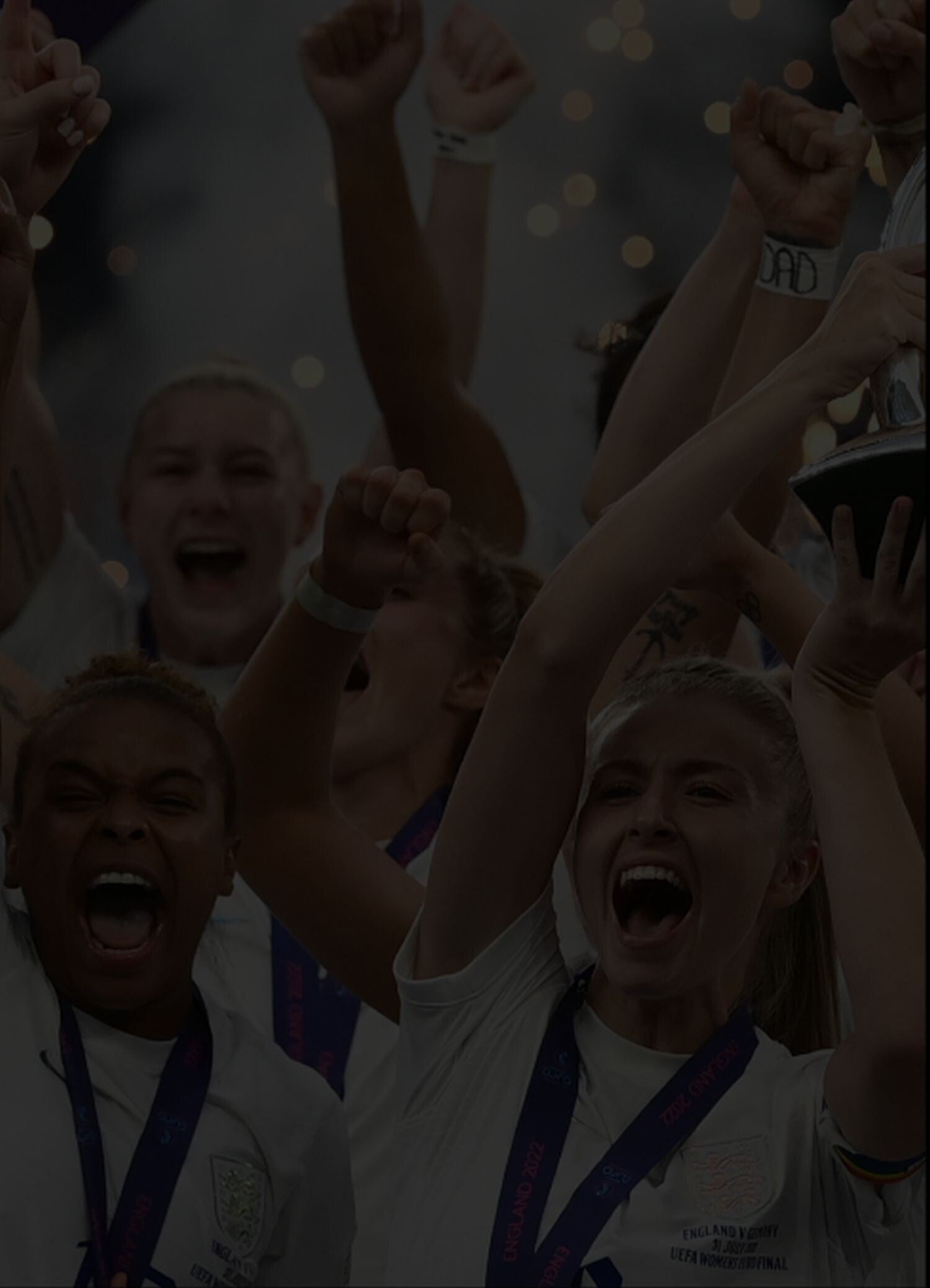

In summer 2025, a grassroots movement known as Operation Raise the Colours encouraged communities to festoon their towns with national flags, especially the St George’s Cross.

Organisers presented it as a non-partisan expression of pride in England’s identity, particularly during the Women’s Euro 2025 football tournament.

Supporters argue it’s about reclaiming the flag from extremists — making it a symbol of belonging for everyone in England, not just the far right.

Many ordinary residents enthusiastically joined in, raising money to buy flags and celebrate their communities.

But controversy quickly followed.

Some organisers had links to far-right figures, and extremist groups openly endorsed the campaign.

Councils in places like Birmingham removed flags put up without permission, citing safety concerns, but critics argued that councils acted more swiftly against English flags than against foreign ones — a charge that inflamed feelings of resentment.

National newspapers and broadcasters seized on the row. Was this a patriotic revival, or the creeping advance of exclusionary nationalism?

Lessons from the Swastika’s Transformation

Here, the lessons of Nazi Germany’s swastika are instructive. The danger is not that the St George’s Cross is inherently racist — it is not. The danger lies in who is allowed to control its meaning.

In 1920s Germany, many citizens might have dismissed the swastika as just another symbol among many.

But as the Nazis gained power, they monopolised it, using it to exclude Jews and suppress dissent until it became synonymous with terror.

The lesson is clear: when extremists seize a national symbol, those who reject their ideology face a choice.

Either they cede the symbol entirely, allowing it to be defined by hate, or they reclaim it loudly and insistently for everyone.

This is the dilemma facing Britain today with the St George’s Cross.

Reclaiming the Flag: Can It Be Done?

There are precedents for reclaiming contested symbols. In the 1990s and 2000s, campaigns sought to rehabilitate the St George’s Cross by encouraging its display during football tournaments, unlinked from extremist politics.

The 1996 song Three Lions — “It’s coming home” — became an anthem of harmless sporting patriotism, helping shift associations away from violence and exclusion.

Similarly, in the United States, the rainbow flag of the LGBTQ+ movement was once mocked or derided, but is now widely recognised as a positive symbol of pride and inclusion. Symbols change when communities actively reshape their meaning.

But reclamation is not easy. Extremist groups thrive on symbols precisely because they know their power. If the St George’s Cross becomes dominated by exclusionary voices, it risks repeating the swastika’s fate: transformed from a benign emblem into a divisive weapon.

The Role of Leaders and Institutions

One critical factor in shaping symbols is leadership. In Nazi Germany, Hitler personally dictated the swastika’s adoption as a state flag. His control over its meaning was absolute.

In Britain today, leaders have taken a different tack.

Keir Starmer, Labour leader, has explicitly encouraged people to fly the St George’s Cross, warning that abandoning it to the far right would be a mistake.

Figures in the Conservative Party and Reform UK have likewise framed flag-flying as a positive expression of patriotism.

Yet leaders also have a responsibility to set boundaries.

Endorsing flag displays is one thing; turning a blind eye to intimidation carried out under that flag is another.

The challenge is to celebrate patriotism without fuelling nationalism.

Patriotism That Includes vs Nationalism That Excludes

So what would an inclusive patriotism look like? Perhaps it means flying the St George’s Cross alongside the Union Jack, the Welsh Dragon, or the Saltire — recognising the diversity within the UK. Perhaps it means ensuring that community flag campaigns are paired with outreach to minority groups, to make clear that the flag belongs to them too.

Nationalism, by contrast, thrives on drawing lines: “real” English people versus “outsiders,” “patriots” versus “traitors.” It uses symbols to intimidate rather than unite.

The swastika was the most extreme example, but it is not unique.

The challenge of the 21st century is to prevent symbols like the St George’s Cross from being bent to similar ends.

Conclusion: The Choice Is Ours

Flags are powerful. They are shorthand for identity, history, and belonging.

But they are not fixed in meaning.

The swastika shows how quickly a symbol can be transformed from a good-luck charm into a global emblem of hate.

The St George’s Cross shows how national symbols can be caught between pride and prejudice, celebration and exclusion.

The question is not whether the St George’s Cross should be flown — it is whether Britain allows it to be monopolised by extremists, or whether it can be reclaimed as a shared symbol of inclusive pride.

Patriotism is not the same as nationalism.

One unites; the other divides.

One celebrates diversity within a nation; the other demands conformity.

If the history of the swastika teaches anything, it is that we must guard carefully the meanings we allow our symbols to carry.

And that decision, ultimately, is ours.

Add comment

Comments