The German occupation of France during World War II was a period marked by profound social, political, and moral upheaval.

Following the swift defeat of French forces in 1940, France found itself divided under a harsh military occupation in the north and an ostensibly autonomous regime in the south, led by Marshal Philippe Pétain from Vichy.

This division set the stage for a complex and often conflicting relationship between the French people, the German occupiers, and the Vichy administration.

Across these four years, the occupation would reshape not only the lives of millions of French citizens but also the trajectory of France's post-war identity and political landscape.

...a repressive surveillance state...

Understanding occupied France requires an exploration of its internal contradictions: the daily survival under occupation, the moral choices between resistance and collaboration, and the cultural and ideological divisions that left lasting scars on French society.

Ordinary life under occupation was marred by scarcity, propaganda, and a repressive surveillance state, yet many aspects of culture and social life adapted in subtle and unexpected ways.

The French resistance, both celebrated and fragmented, emerged as a powerful but perilous force, challenging the German presence while facing challenges of organization and support.

...exposed the darker sides of French society...

At the same time, collaboration with German authorities, whether voluntary or coerced, exposed the darker sides of French society, as some individuals and institutions chose or felt forced to align with the occupiers.

This article delves into the multifaceted experience of occupied France, examining the realities of daily life, the resistance and collaboration dynamics, and the complex moral landscape that defined this era.

By looking closely at these themes, we can better understand the enduring impact of the occupation on France's national memory and the ways in which this period has shaped modern French identity.

The Fall of France and the Establishment of the Vichy Regime

The German invasion of France in 1940 shocked Europe and reshaped the trajectory of the Second World War.

The rapidity of France’s collapse led to a drastic reconfiguration of French governance and territory, forcing the nation into a period of division, with occupied and unoccupied zones.

This section explores the German military strategy that led to France’s fall, the terms of the armistice that followed, the establishment and ideology of the Vichy regime, and the complex impact of this territorial division on the French population and political identity.

...encircling and overwhelming French and British troops...

The invasion of France by Nazi Germany began in May 1940 as part of the larger “Blitzkrieg” strategy that had already proven devastating in Poland. The Germans launched their offensive through the Ardennes—a route thought to be impassable for a large army and therefore poorly defended by the French.

This manoeuvre bypassed the heavily fortified Maginot Line, a string of defensive fortifications built along the French-German border. Within weeks, German forces had swiftly advanced, encircling and overwhelming French and British troops and capturing Paris by June 14.

The rapid defeat stunned not only France but the entire world, which had considered France one of Europe’s major military powers.

...internal fractures within French society...

France’s surrender was not solely the result of German tactical superiority; it was also influenced by internal fractures within French society, including political instability, class tensions, and trauma from the First World War.

These divisions contributed to a swift demoralization among both the French military and civilians.

Faced with the complete collapse of defenses and with the British army evacuated from Dunkirk, French leaders sought an armistice, hoping to preserve what little remained of French autonomy.

...nominally autonomous under strict German oversight...

Signed on the 22nd June 1940, in the Compiègne Forest, the Franco-German armistice formalized France's surrender and set stringent terms that would define the coming years of occupation.

Under the armistice, Germany retained control over northern France, including Paris, while southern France was left under the jurisdiction of an unoccupied "Free Zone" governed from the town of Vichy.

The Vichy administration, however, remained nominally autonomous under strict German oversight and influence.

...a subordinate power within Nazi Germany’s European empire...

The armistice terms required France to disband large portions of its military, greatly reduce its sovereignty, and bear the financial burden of German occupation, effectively making it a subordinate power within Nazi Germany’s European empire.

Additionally, the French government was expected to assist Germany in the war effort indirectly, refraining from actions that could benefit the Allies and providing material resources and economic support to the occupying forces.

The division into the Occupied Zone in the north and the Free Zone in the south would create a physically and psychologically fragmented nation, complicating communication, transportation, and social unity.

...eroded by the political turmoil and moral decline...

With the armistice, France’s government moved to Vichy, where Marshal Philippe Pétain, a revered First World War hero, took control as the head of state.

Pétain’s administration promoted a vision of “Révolution Nationale” (National Revolution), seeking to restore conservative French values that, in its view, had been eroded by the political turmoil and moral decline of the interwar years.

The Vichy regime emphasized traditional values such as family, work, and religious piety, positioning itself as a moral and cultural counterpoint to the secular, left-leaning politics of pre-war France.

Slogans such as “Travail, Famille, Patrie” (Work, Family, Fatherland) embodied the ideological pivot of Vichy, which aimed to reject the ideals of the French Revolution in favor of a highly nationalist, authoritarian state.

...eroded by the political turmoil and moral decline...

The Vichy government wielded considerable control over the Free Zone and administered policies independently, albeit with a watchful eye from the Germans.

Vichy France was complicit in numerous Nazi policies, particularly those targeting Jews, communists, and resistance groups.

The regime introduced its own anti-Semitic laws and policies, even surpassing some of the requirements set by German authorities.

Pétain and other Vichy officials framed these actions as necessary for preserving the national order and preventing total German control, though many scholars argue that Vichy was driven by ideological alignment with certain aspects of Nazi beliefs rather than pure pragmatism.

...systematically exploited to support the German war effort...

Marshall Pétain, A hero of the first world war, he would sully his name in the second when, in 1940, he headed the Vichy government.

After the war, Pétain was tried and convicted for treason, and sentenced to death, but the new president, De Gaulle, commuted the sentence to life imprisonment.

France’s division into occupied and unoccupied zones had far-reaching implications for daily life, governance, and the economy.

The Occupied Zone encompassed Paris and much of the industrial heartland of northern France, where the German presence was most direct and restrictive.

Here, citizens faced intense scrutiny, rationing, and German military surveillance. Economic resources from this area were systematically exploited to support the German war effort, creating widespread scarcity and suffering.

The Occupied Zone became a space of daily fear and repression, with Germans monitoring all communications and transport, curtailing civil liberties, and implementing strict curfews.

Street signs advertise locations of German facilities in Paris, with their French names written in smaller text beneath. During the occupation of Paris, German forces established extensive infrastructure to control and monitor the city. They commandeered buildings for military headquarters, established checkpoints, and implemented communication and transportation networks to support surveillance and troop movements, consolidating their control.

https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/color-photos-of-occupied-paris-zucca/

André Zucca / Bibliothèque historique de la ville de Paris / Wikimedia Commons / TopFoto / Captions from Daily Mail UK)

...undermining the notion of true independence...

In contrast, the Free Zone initially retained a degree of autonomy, allowing Vichy to exercise authority and attempt to preserve a semblance of national sovereignty.

However, the autonomy of the Free Zone was superficial; Vichy collaborated extensively with German authorities, especially in areas of policing and economic policy, thus undermining the notion of true independence.

The demarcation line dividing the zones was heavily guarded, restricting movement and isolating families and communities. This separation reinforced a sense of national fragmentation, eroding unity and adding to the challenges of mounting any coherent resistance movement.

...undermining the notion of true independence...

The separation between the zones persisted until November 1942, when the German military moved to occupy the Free Zone following the Allied landings in North Africa. This move marked the end of even nominal French autonomy, as Vichy became a puppet regime under complete German control.

The occupation of both zones intensified repression and left few safe havens for those opposing Nazi rule, transforming France into a thoroughly controlled territory within Hitler’s European order.

Through this division, Vichy’s policies, and the enduring trauma of defeat, the fall of France left a nation in turmoil, its unity fractured and its citizens subjected to a daily reality shaped by fear, scarcity, and moral ambiguity.

The repercussions of this division and the Vichy government’s collaboration would reverberate through French society long after the end of the occupation.

German soldiers march down one of Paris’s broad boulevards. The presence of German soldiers in Paris drastically altered daily life, creating an atmosphere of fear and surveillance. Parisians faced restrictions, curfews, and rationing while soldiers occupied public spaces, commandeered resources, and imposed strict controls, impacting social, economic, and cultural activities.

https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/color-photos-of-occupied-paris-zucca/

André Zucca / Bibliothèque historique de la ville de Paris / Wikimedia Commons / TopFoto / Captions from Daily Mail UK)

The Occupying Forces

The German occupation of France during World War II was a critical phase in the Nazi regime's military strategy and its attempt to control Western Europe.

Following the swift defeat of French forces in May and June 1940, France was divided into occupied and unoccupied zones, with the German forces maintaining direct control over the northern part, including Paris, and the coastal regions.

This occupation was overseen by a series of high-ranking German commanders and supported by various military units and administrative structures designed to enforce Nazi policies and maintain order.

...stringent control measures...

Initially, the occupation was governed by General Otto von Stülpnagel, who served as the military governor from 1940 until 1942.

His leadership established a repressive regime characterized by stringent control measures, including curfews, censorship of the press, and rigorous surveillance of the population.

Von Stülpnagel aimed to maintain stability while extracting resources from France to support the German war effort.

He was replaced by General Carl-Heinrich von Stülpnagel, who continued the harsh policies amid growing resistance activities.

...countering potential Allied incursions...

The German military presence in occupied France was substantial. The Wehrmacht deployed several divisions, including infantry, armored units, and specialized forces like the SS (Schutzstaffel), which conducted operations against resistance groups.

Army Group D, commanded by Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, was one of the principal formations responsible for the defense of occupied France and for countering potential Allied incursions.

The German forces utilized a variety of military resources, including tanks, artillery, and aircraft, establishing strong points and fortifications along the Atlantic coastline as part of the extensive Atlantic Wall defensive system.

...coerced into supplying war materials...

One of the primary strategies employed by the Germans in France was the systematic exploitation of the country’s economic resources.

The German authorities requisitioned food, fuel, and raw materials, diverting them to support their military campaigns elsewhere in Europe.

French industries were coerced into supplying war materials, and forced labor became a central policy, with thousands of French men and women conscripted into labor camps or sent to work in German factories, often under harsh conditions.

This exploitation not only strained the French economy but also bred resentment among the population.

...widespread arrests and deportations...

In terms of governance, the German occupation administration implemented harsh policies aimed at suppressing any form of dissent.

The Gestapo, the secret police, and the Sicherheitsdienst (SD, or Security Service) operated extensively throughout occupied France, arresting suspected resistance members, political opponents, and Jews.

The Nazi regime enforced anti-Semitic laws that restricted the rights of Jewish citizens, leading to widespread arrests and deportations to concentration camps.

The establishment of internment camps and the implementation of the Final Solution further exacerbated the suffering of Jews and other targeted groups in France.

...violence against civilians...

The behaviour of German forces in occupied France ranged from oppressive to brutal.

While some soldiers treated the French populace with a degree of civility, many others enforced the regime's harsh policies with brutality.

Acts of violence against civilians were not uncommon, especially in response to resistance actions.

For example, in retaliation for resistance activities, entire towns could face collective punishment, including executions and destruction.

...catalyzed a growing resistance...

Despite the severe repression, the German occupation catalyzed a growing resistance movement in France.

Various groups formed to sabotage German operations, assist Allied forces, and support the persecuted, particularly the Jewish community.

These resistance efforts eventually gained momentum, leading to increased coordination and effectiveness, especially as the war progressed.

...a complex interplay of military strategies...

The German occupation of France was marked by a complex interplay of military strategies, brutal policies, and administrative control aimed at exploiting the country while suppressing dissent.

The occupation left a profound impact on the French people, shaping their experiences of war and resistance, and ultimately setting the stage for the country’s liberation in 1944.

The legacy of this period continues to resonate in France’s historical memory and collective identity.

Daily Life Under Occupation

The German occupation of France during the Second World War brought dramatic changes to the daily lives of French citizens, shaping their experiences through pervasive restrictions, economic hardships, and social adjustments.

Although the daily reality varied depending on location and social status, French citizens across both the Occupied and Free Zones grappled with resource scarcity, government propaganda, and shifts in family and social roles.

Understanding the material and psychological conditions of life under occupation provides essential insight into how the French endured this period and adapted to its challenges.

Guard posts stand outside a building the sign of which advertises it as an important spot for the occupying German army. During the occupation of France, the German Army established strict control, enforcing harsh policies that suppressed resistance and exploited resources. Stationed across the country, they collaborated with the Vichy regime, seizing French goods, industries, and infrastructure for Nazi Germany's war efforts.

https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/color-photos-of-occupied-paris-zucca/

André Zucca / Bibliothèque historique de la ville de Paris / Wikimedia Commons / TopFoto / Captions from Daily Mail UK)

...significantly limited social interaction and mobility...

The German presence in France was both an obvious and subtle force. Throughout the Occupied Zone, the Germans imposed a series of restrictions that extended into nearly every aspect of daily life, from movement and work to communication and social gatherings.

The military curfews, for instance, significantly limited social interaction and mobility, while travel restrictions across the demarcation line dividing the Occupied and Free Zones isolated families and disrupted commerce.

Surveillance by the German military police, known as the Feldgendarmerie, further ensured compliance, instilling a sense of unease and caution among citizens.

Giant Swastikas line the streets of the French capital, Paris. The swastika flags flown across Paris symbolized German dominance and deeply affected French morale. Their presence on iconic sites like the Eiffel Tower underscored the nation's subjugation, evoking fear, anger, and a painful reminder of lost sovereignty under occupation.

https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/color-photos-of-occupied-paris-zucca/

André Zucca / Bibliothèque historique de la ville de Paris / Wikimedia Commons / TopFoto / Captions from Daily Mail UK)

...sought to influence public opinion...

Propaganda was another powerful tool employed by the Germans to control civilian sentiment.

Through German-controlled media outlets, newspapers, and cinema, the occupation authorities sought to influence public opinion by presenting the Nazis as France’s protectors against perceived internal and external threats, especially the Allies.

This propaganda also aimed to discredit the French Resistance and marginalize political groups opposing the occupation.

Messages promoting cooperation and mutual benefit between France and Germany were frequent, designed to cultivate a sense of normalization despite the occupation’s oppressive nature.

The propaganda was often met with quiet resistance, though it influenced some segments of society.

Parisians fishing in the Seine. during the occupation. Despite hardships, Parisians adapted to occupation, with daily routines, cafes open, and cultural life persisting subtly, under constant German surveillance.

https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/color-photos-of-occupied-paris-zucca/

André Zucca / Bibliothèque historique de la ville de Paris / Wikimedia Commons / TopFoto / Captions from Daily Mail UK)

...food shortages led to widespread malnutrition...

Economic hardship defined daily life for most French citizens under the occupation, as the Germans prioritized their own needs, redirecting French resources to support the German war effort. Food, fuel, and other essential goods became scarce, with shortages exacerbated by German requisitions and resource redirection to the Eastern Front.

Rationing became a defining aspect of life, as French citizens received food coupons for basic supplies like bread, meat, sugar, and coffee. The black market quickly grew in response, providing an alternative for those who could afford it, while the working and lower classes were often left to manage with limited resources.

The nutritional deficiencies caused by food shortages led to widespread malnutrition and a decline in public health, with especially severe effects on children and the elderly.

In Paris, this citizen owns a car equipped to run on natural gas. During the occupation, fuel shortages forced Parisians to modify cars to run on alternative sources like wood gas, produced by burning wood or charcoal in gas generators. This made transportation challenging, as conventional fuel was prioritized for German military needs.

https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/color-photos-of-occupied-paris-zucca/

André Zucca / Bibliothèque historique de la ville de Paris / Wikimedia Commons / TopFoto / Captions from Daily Mail UK)

...forced labor participation created complex moral and social dilemmas...

The economy also suffered from the introduction of German-imposed forced labor policies. Under the Service du Travail Obligatoire (STO) instituted in 1942, many French men were required to work in Germany to support its industries.

The STO was deeply resented, leading some French workers to evade conscription by joining the French Resistance or fleeing to rural areas.

Despite its coercive nature, forced labor participation created complex moral and social dilemmas, as families struggled with the consequences of compliance versus resistance to the policy.

As more men left for Germany, their absence also placed additional burdens on those who remained, especially women, who increasingly took on roles outside the home.

Fashionable young women relax in the French capital during the German occupation. Fashion in occupied Paris adapted to wartime shortages, with materials like silk and leather rationed. Parisians embraced creativity, repurposing old clothes and using substitute fabrics like rayon. Despite constraints, French designers continued innovating, symbolizing resilience and defiance through style.

https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/color-photos-of-occupied-paris-zucca/

André Zucca / Bibliothèque historique de la ville de Paris / Wikimedia Commons / TopFoto / Captions from Daily Mail UK)

...embedding veiled criticisms of the occupation...

In adapting to the occupation, French citizens demonstrated remarkable resilience, finding ways to preserve cultural identity, maintain morale, and support one another.

Despite German censorship, French culture persisted, though often in subtle or coded forms.

Artists, writers, and filmmakers continued to create, sometimes embedding veiled criticisms of the occupation in their work.

Music and theater, for instance, became forms of subtle resistance, where symbolic references could rally French pride or comment on the oppression experienced by the populace.

Parisians cycle past a poster for Nazi-sponsored Europe Against Bolshevism exhibition. Under Nazi occupation, the French faced relentless propaganda aimed at promoting German ideals and Vichy collaboration. Many ignored or subtly defied these messages, seeking news from underground Resistance publications and BBC broadcasts, maintaining a sense of resilience and cultural identity.

https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/color-photos-of-occupied-paris-zucca/

André Zucca / Bibliothèque historique de la ville de Paris / Wikimedia Commons / TopFoto / Captions from Daily Mail UK)

...both spiritual and material assistance...

Social cohesion became essential as families, neighborhoods, and informal groups relied on one another to cope with the shortages, fear, and disruptions of daily life.

The communal sharing of resources, skills, and support networks helped individuals manage the psychological strain and fostered a sense of solidarity.

Religious gatherings also played a role in supporting communities, as churches offered both spiritual and material assistance to those struggling under the hardships of the occupation.

These communal efforts allowed citizens to maintain a semblance of normalcy, even as they confronted the realities of oppression.

Life goes on: Parisians go about their business, walking down into a subway. During the German occupation, public transport in Paris was tightly controlled, with many routes reduced and vehicles repurposed for German use. Fuel shortages led to overcrowded trams and buses, while curfews restricted travel, challenging Parisians' daily commutes and routines.

https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/color-photos-of-occupied-paris-zucca/

André Zucca / Bibliothèque historique de la ville de Paris / Wikimedia Commons / TopFoto / Captions from Daily Mail UK)

...women took on additional responsibilities...

The occupation period also marked significant shifts in family dynamics and gender roles, as the absence of men and the demands of survival reshaped traditional expectations.

With many men conscripted for forced labor or involved in resistance activities, women took on additional responsibilities, both within their families and in the workplace.

Women increasingly managed family finances, navigated rationing systems, and often took on labor-intensive jobs previously dominated by men.

These roles, while initially born out of necessity, led to shifts in public perception regarding women’s capabilities and contributions to society.

A wealthy-looking man and woman ride in a cart pulled by two slim Parisians on a tandem bicycle. During the occupation, French women took on diverse roles, filling jobs in factories, farms, and public services due to male conscription. Some engaged in resistance efforts, working as couriers or spreading information, while others managed households under difficult rationing conditions.

https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/color-photos-of-occupied-paris-zucca/

André Zucca / Bibliothèque historique de la ville de Paris / Wikimedia Commons / TopFoto / Captions from Daily Mail UK)

...challenged the traditional gender norms...

This change extended into the realm of resistance as well. Many women participated actively, often serving as couriers, intelligence gatherers, or even armed fighters within resistance groups.

Though their contributions were frequently overlooked in the immediate post-war period, the experiences of female resistance fighters challenged the traditional gender norms and highlighted the critical role women played in the struggle against occupation forces.

Their involvement in the resistance was a notable departure from pre-war expectations, and it helped catalyze later changes in women’s rights and societal roles in post-war France.

...differing stances on the occupation created moral and ethical rifts...

For families, the constant threats posed by the occupation brought both unity and strain. Parents struggled to shield their children from the trauma of daily life under German rule, while the scarcity of resources added new stress to family relationships.

The occupation reinforced the importance of familial bonds for many, as families relied on each other emotionally and materially, despite the pervasive uncertainties.

However, collaboration or resistance choices within families sometimes led to divisions, as differing stances on the occupation created moral and ethical rifts.

...challenges imposed by a harsh and unyielding regime...

The pressures of occupation thus profoundly affected French society’s structure, from resource allocation and employment patterns to shifts in family life and gender roles.

These daily adjustments to survive under German rule reflected the broader complexities of life in occupied France, as individuals and communities grappled with maintaining their identity, dignity, and sense of solidarity amid the challenges imposed by a harsh and unyielding regime.

Understanding these social and economic adaptations reveals the resilience and resourcefulness that defined life under occupation, as well as the nuanced survival strategies that allowed French society to endure and, ultimately, to contribute to the liberation of France.

The French Resistance

The French Resistance emerged as a response to the German occupation and the collaborationist policies of the Vichy regime.

It represented a diverse and fragmented yet determined effort to disrupt Nazi control in France, fueled by the desire to restore French sovereignty and protect national identity.

Though initially limited in scope, resistance grew over time, drawing individuals from various political, social, and economic backgrounds.

This section examines the origins and motivations of the Resistance, the main groups and leaders involved, the diverse tactics they employed, and the critical contributions of women, whose roles in the Resistance were often overlooked yet essential.

French Resistance poster, 1944.

https://www.reddit.com/r/PropagandaPosters/comments/8wuwey/french_resistance_poster_1944/

...left many citizens demoralized...

The French Resistance began with small acts of defiance, as isolated individuals and groups protested the German occupation and the Vichy government’s compliance with Nazi policies. In the early years of occupation, resistance was sporadic and loosely organized.

The quick and unexpected fall of France in 1940 left many citizens demoralized and in shock, while the Vichy regime’s collaboration with the Germans led to confusion and frustration among those who had once trusted the government.

Initially, only a small number of people, often with connections to the military, communists, or Gaullists, took action against the occupation.

Members of French Resistance in Boulogne. The men and women of the French Resistance showed remarkable bravery, risking their lives to defy Nazi occupiers and the Vichy regime. They gathered intelligence, distributed anti-German propaganda, sabotaged military operations, and aided Allied forces. United by a commitment to freedom, these individuals faced torture, imprisonment, and death, symbolizing France’s indomitable spirit.

https://www.reddit.com/r/Colorization/comments/f1rb9f/members_of_french_resistance_in_boulognemer/

...actively hunted suspected resistors...

General Charles de Gaulle’s broadcast from London on the 18th June 1940, calling on the French to continue fighting, became a rallying cry and a source of inspiration for early resistance.

Though relatively few responded at first, de Gaulle’s message encouraged those opposed to the occupation to see themselves as part of a broader fight for French independence.

Despite the motivation, resistance efforts faced formidable challenges: the Gestapo and the French police actively hunted suspected resistors, and the pervasive surveillance by German and Vichy authorities made organizing difficult.

Early resisters risked imprisonment, torture, and execution, creating an atmosphere of fear that inhibited organized dissent.

General Charles de Gaulle. De Gaulle was a central figure in the French Resistance, leading the Free French forces from exile in London. Through broadcasts on the BBC, he encouraged resistance within occupied France, organized French forces abroad, and worked with the Allies to coordinate liberation efforts, ultimately becoming a symbol of French resilience.

https://www.deviantart.com/henriquemart/art/Charles-de-Gaulle-903087843

Identity document of French Resistance fighter Lucien Pélissou. The French Resistance used fake IDs to avoid Nazi detection and navigate strict checkpoints. Forged identification allowed them to move freely, deliver crucial information, transport supplies, and support escape routes for targeted individuals, including Jews and other members of the Resistance.

...became known for its aggressive tactics...

In Occupied France during the war, reproductions of De Gaulles 18th June appeal were distributed through underground means as pamphlets and plastered on walls as posters by supporters of the Résistance. This could be a dangerous activity.

As resistance efforts grew, various groups emerged, each with its ideological foundation, leadership, and methods. Among the most influential were the Francs-Tireurs et Partisans (FTP), the Mouvement Combat, and groups linked to de Gaulle’s Free French Forces.

The FTP, originally founded by French communists, became known for its aggressive tactics, including sabotage, bombings, and attacks on German soldiers.

The communist ideology of the FTP sometimes created tension with other resistance groups, particularly those aligned with de Gaulle or the conservative elements of French society.

However, despite political differences, the FTP proved to be one of the most resilient and widespread resistance organizations.

Paratroopers and FTP members during the Battle of Normandy, summer 1944. The Francs-Tireurs et Partisans (FTP) was a major French Resistance group during WWII, known for its communist ties and guerrilla warfare tactics. It conducted sabotage operations, assassinations of German officials, and helped rally fighters across France to resist Nazi occupation and collaborationist forces.

...helping to bridge ideological divides...

Another major group was the Mouvement Combat, founded by Henri Frenay and influenced by French nationalism.

This organization coordinated with the Forces Françaises de l'Intérieur (FFI) and eventually aligned with de Gaulle’s Free French Forces.

Movements like Combat sought to unify the Resistance, helping to bridge ideological divides and strengthen coordination among the different factions.

They focused on gathering intelligence for the Allies, publishing underground newspapers to counter German propaganda, and conducting acts of sabotage.

...creating an organized network for effective collaboration...

General de Gaulle’s leadership from London fostered the consolidation of these resistance groups into a more unified force, especially after 1942, when he created the Conseil National de la Résistance (CNR) under the leadership of Jean Moulin.

Moulin, a former civil servant, was instrumental in unifying the diverse factions under de Gaulle’s authority.

The CNR provided the Resistance with a clearer political and military structure, aligning local groups with the Allies and creating an organized network for effective collaboration in preparation for the Allied invasion.

...acts of sabotage were risky...

The French Resistance employed various tactics to disrupt German operations and gather intelligence for the Allied forces.

Sabotage was a primary method; resistance members targeted railways, bridges, and supply depots to delay German troop movements and supplies, particularly as the Allies prepared for the D-Day landings in 1944.

These acts of sabotage were risky and required a high level of skill and coordination, as Germans often responded with severe reprisals, executing or imprisoning anyone suspected of involvement.

French resistance manning a barricade, Paris, 1944. The French Resistance played a crucial role in the liberation of Paris by organizing uprisings, gathering intelligence for Allied forces, and disrupting German supply lines. Their efforts weakened German control, paving the way for Allied troops to enter and reclaim the capital.

...an essential role in intelligence efforts...

Intelligence gathering was another vital role of the Resistance. Resisters infiltrated German military offices and communicated with local officials to obtain crucial information on troop movements, fortifications, and military strategies.

This intelligence was relayed to the Allies, helping them plan their operations and assess German strengths and weaknesses. La Résistance, an underground newspaper network, also played an essential role in intelligence efforts by distributing information and raising morale among the French populace.

These publications, such as Combat and Libération, defied German censorship, keeping citizens informed and helping to counteract Nazi propaganda.

...efforts became increasingly significant...

The Resistance also engaged in guerrilla warfare, using hit-and-run tactics to weaken German forces.

Small, mobile units, known as maquisards, took refuge in rural and mountainous regions where they could evade detection more easily.

The maquis fighters ambushed German convoys, attacked Vichy collaborators, and even freed prisoners from German custody.

The maquis represented a critical force in rural areas, and their efforts became increasingly significant as the war progressed, especially in the months leading up to the Liberation, when the Resistance played an active role in assisting the Allied invasion.

...carrying intelligence across checkpoints...

Women played indispensable roles in the Resistance, though their contributions were often overlooked in official narratives.

Many women worked as couriers, delivering messages and supplies between resistance cells and carrying intelligence across checkpoints.

Their ability to move more freely than men—since they were less likely to be suspected of resistance activity—made them ideal for such roles, though they faced considerable risk if discovered.

...subverting them through subtle persuasion...

Some women, such as Lucie Aubrac and Geneviève de Gaulle-Anthonioz, held leadership positions and became symbols of resilience and bravery.

Lucie Aubrac famously organized daring rescues for imprisoned Resistance members, while Geneviève, niece of Charles de Gaulle, actively participated in underground operations.

Women also contributed to the psychological warfare aspect of resistance, gathering information from German soldiers and Vichy officials or subverting them through subtle persuasion and strategic alliances.

...demonstrated courage and adaptability...

Despite these vital roles, women in the Resistance often faced additional challenges, including societal biases that undervalued their contributions.

Post-war narratives frequently marginalized female resistors, with some recognition delayed for decades.

Nonetheless, their impact was significant: women’s efforts in supporting and organizing resistance activities demonstrated courage and adaptability, expanding traditional gender roles and marking a shift in French society’s perception of women’s capabilities.

...a testament to resilience and patriotism...

The diverse, determined, and often dangerous efforts of the Resistance contributed immensely to the eventual liberation of France, weakening German control and providing crucial support to the Allies.

Through acts of sabotage, intelligence gathering, guerrilla warfare, and the contributions of women, the French Resistance became a testament to resilience and patriotism.

Their efforts not only undermined the occupation but also left a profound legacy on French national identity, celebrated in France’s post-war culture and collective memory.

Collaboration with the German Forces

Collaboration during the German occupation of France was a complex and multifaceted phenomenon. It spanned from direct cooperation with Nazi authorities by French officials to more passive forms of complicity by individuals and businesses.

While some engaged in collaboration out of ideological alignment with Nazi principles, others were motivated by self-preservation, economic gain, or a sense of pragmatism.

Understanding the nature of collaboration illuminates the moral ambiguities faced by individuals and institutions under occupation, as well as the enduring scars these choices left on French society.

This section examines the motivations for collaboration, the role of the Milice and French police, prominent collaborators, and the moral complexities that blurred the lines between coercion and complicity.

...resonated with the authoritarian and nationalist ideals...

A mystery young French girl dressed in her presumably German boyfriends uniform.

Collaboration was not a monolithic choice but rather a spectrum of behaviors influenced by various factors. Some French citizens were ideologically aligned with fascist and anti-Semitic doctrines.

For them, collaboration with the Nazis represented a chance to realize a new order in France, one that resonated with the authoritarian and nationalist ideals that Marshal Philippe Pétain’s Vichy government promoted through its “Révolution Nationale.”

These collaborators saw Germany as a defender of Europe against the perceived threats of communism, liberalism, and Anglo-American dominance.

Far-right French groups like La Cagoule and individual supporters of Pétain and the Vichy state championed such views, advocating for a society built on “traditional” values of family, faith, and order.

...supplied vehicles and machinery to the German army...

Economic motivations also played a significant role in encouraging collaboration. Many French business owners and industrialists saw an opportunity to profit by cooperating with the German occupiers.

The German military needed resources, manufactured goods, and labor to support their war effort, and businesses that catered to these demands could reap financial rewards.

Corporations like Renault supplied vehicles and machinery to the German army, while other companies provided raw materials and logistics support.

Farmers, factory owners, and even ordinary merchants found economic benefits in collaborating, especially under the pressures of rationing and scarcity.

However, the pursuit of financial stability often entailed difficult ethical compromises, as companies and workers alike were forced to balance survival with collaborationist policies.

...blurred the lines between survival and moral compromise...

Pragmatic motivations also influenced collaboration. For some individuals and officials, working with the occupiers was a matter of survival, driven by the belief that compliance might mitigate the worst excesses of German rule.

Certain French officials and bureaucrats hoped that by working with the Nazis, they could retain a measure of control over their own communities and prevent harsher repercussions.

This approach sometimes allowed French authorities to mediate local policies or alleviate certain pressures on the civilian population.

However, pragmatism also blurred the lines between survival and moral compromise, as the acts that were initially framed as necessary concessions often led to deeper entanglements with Nazi demands.

...often using torture and extrajudicial executions...

Among the most visible and reviled agents of collaboration were the Milice and the French police, both of which played central roles in maintaining order and enforcing German policies.

The Milice, created in 1943 under the leadership of Joseph Darnand, was a paramilitary force that supported Vichy’s collaborationist agenda, targeting members of the Resistance, Jews, communists, and other perceived enemies of the state.

While initially focused on countering the Resistance, the Milice grew notorious for its brutal tactics, often using torture and extrajudicial executions to intimidate opponents and demonstrate loyalty to the German occupiers.

Many Milice members were fervent ideologues who believed in Vichy’s vision for France, while others were motivated by personal grievances or the material rewards that collaboration could bring.

...enacted its own series of anti-Jewish laws...

The French police, too, were complicit in enforcing German policies, particularly in anti-Semitic actions.

Vichy enacted its own series of anti-Jewish laws, but French police forces went further, assisting German authorities in the notorious Rafle du Vel' d'Hiv in July 1942, when they rounded up over 13,000 Jewish men, women, and children in Paris, who were then sent to internment camps and ultimately to Auschwitz.

The complicity of the French police in such operations highlighted the extent to which Vichy’s collaboration was not just passive but active, with state resources mobilized to support Nazi policies.

For many in France, this collaboration remains one of the darkest stains on the Vichy regime’s record.

...authorizing the forced labor of French workers...

Throughout the occupation, certain individuals emerged as emblematic figures of collaboration. Pierre Laval, a prominent politician who served as Pétain’s head of government, was one of the most infamous.

Laval actively worked to align Vichy’s policies with Nazi goals, advocating for closer collaboration and authorizing the forced labor of French workers in Germany under the Service du Travail Obligatoire (STO).

He publicly espoused a policy of “productive cooperation” with Germany, viewing collaboration as necessary for preserving some degree of French autonomy.

Laval’s policies were deeply unpopular, and he was later tried and executed for treason after the war.

...endorsed anti-Semitic rhetoric...

Another prominent figure was **Jacques Doriot**, a former communist who became a vocal proponent of fascism and leader of the French Popular Party (PPF), a far-right group that supported Nazi ideology.

Doriot and the PPF endorsed anti-Semitic rhetoric, glorified the Nazis, and even volunteered soldiers for the Legion of French Volunteers Against Bolshevism, which fought alongside German troops on the Eastern Front.

Doriot’s trajectory from left-wing activist to Nazi collaborator illustrated the complex personal and ideological factors that could drive individuals toward collaboration.

...compelled to comply with German demands...

For many French people, the lines between collaboration, coercion, and survival were not always clear. Some individuals were coerced into cooperation, whether through threats, blackmail, or the fear of reprisals against family members.

For example, business owners might have been compelled to comply with German demands or risk losing their livelihood, facing imprisonment, or even execution.

Likewise, some public officials and police officers, while outwardly compliant, felt they had little choice but to follow Vichy’s orders to avoid severe punishment or protect their families.

This sense of coercion led to the “gray zone” of moral ambiguity, where collaboration could be seen as a forced response rather than a voluntary betrayal.

...moral choices made under occupation...

The complexities of collaboration created deep and lasting rifts within French society.

Those who resisted the occupation often regarded collaborators with disdain, and post-war justice sought to punish those seen as traitors.

However, not all collaborators faced equal repercussions, as the nuances of each individual’s actions, motivations, and degree of choice were challenging to assess.

The legacies of collaboration led to enduring debates in French society about responsibility, accountability, and the moral choices made under occupation.

...others embraced Nazi ideals for personal or ideological gain...

The phenomenon of collaboration in occupied France underscores the difficult moral terrain navigated by individuals and institutions under authoritarian rule.

While some saw collaboration as a means of protecting themselves or preserving France, others embraced Nazi ideals for personal or ideological gain.

The varied responses to occupation—from forced compliance to active support—revealed the challenges of living under a regime that tested loyalty, identity, and survival, leaving an indelible mark on French memory and society.

A German soldier with his French girlfriend.

Propaganda and Cultural Manipulation

During the occupation of France from 1940 to 1944, propaganda and cultural manipulation were crucial tools used by both the German authorities and the Vichy government to maintain control and foster cooperation.

Through radio broadcasts, press censorship, cinema, educational policies, and targeted propaganda campaigns, the occupiers sought to reshape French attitudes and perceptions, creating a pro-German narrative that masked the harsher realities of occupation.

This section examines the role of media under occupation, the impact on art and literature, the influence on education and youth, and the ways in which propaganda tried to manipulate the French public.

This antisemitic map - published in occupied France during the 1940's - showing alleged spheres of influence and global dominance by 'World Jewry'. Such blatant propaganda attempted to stir up suspicion and animosity amongst the French population. During the 1940s, French attitudes toward Jews were deeply divided. While some collaborated with Nazi policies, supporting deportations, others, including members of the Resistance, risked their lives to protect Jewish citizens.

https://www.theholocaustexplained.org/life-in-nazi-occupied-europe/occupation-case-studies/france/

...aiming to replace the independent French press...

Under occupation, the German authorities imposed strict controls over French media, seeing it as a primary means to influence public opinion and suppress dissent.

Newspapers, radio, and cinema—all widely accessible forms of media—were carefully monitored and censored to align with German and Vichy messaging.

German propaganda administrators, notably the Propaganda-Abteilung, managed and regulated news outlets, aiming to replace the independent French press with pro-German publications that reframed the occupation in a positive light.

...the moral decay of the previous government...

Many newspapers, including Le Matin and La Gerbe became collaborators, willingly publishing articles supportive of the German perspective.

They painted Germany as a protector against “Bolshevism” and depicted the Anglo-American allies as dangerous imperialists.

Additionally, they promoted the Vichy regime’s ideology of “Travail, Famille, Patrie” (Work, Family, Fatherland), framing Marshal Pétain as the savior of France from the moral decay of the previous government and glorifying traditionalist, rural values as antidotes to the perceived “corruption” of urban, liberal society.

Independent papers that resisted this narrative were shut down or forced to operate clandestinely, with some joining the French Resistance to publish underground journals like Combat and Libération that spread anti-German and anti-Vichy messages.

...a critical lifeline for those seeking unfiltered news...

Radio broadcasts, one of the most influential media forms of the time, were also harnessed to spread German propaganda.

The German-controlled Radio-Paris broadcast speeches, music, and news with pro-German commentary, discouraging resistance and urging the French to accept German friendship.

In response, the BBC’s French broadcasts from London became a critical lifeline for those seeking unfiltered news and messages from Charles de Gaulle.

Listening to the BBC was banned under penalty of arrest, but many continued to tune in clandestinely, drawn to its counter-narrative and its broadcasts of hope and resilience against Nazi rule.

A sign advertises Europe Against Bolshevism exhibition, held under the auspices of Nazi front organization the anti-Bolshevik Action Committee in Paris in 1942.

https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/color-photos-of-occupied-paris-zucca/

André Zucca / Bibliothèque historique de la ville de Paris / Wikimedia Commons / TopFoto / Captions from Daily Mail UK)

...sought ways to incorporate subtle criticism into their works...

Cinema, as both entertainment and ideological tool, was similarly regulated. French cinemas were required to show German films, particularly propaganda movies such as Le Juif Süss, an anti-Semitic film intended to reinforce Nazi ideology.

German and Vichy films frequently depicted German soldiers as noble and benevolent protectors and glorified the Vichy state. While escapist films—romances, comedies, and musicals—were also permitted, any references to democracy, resistance, or French nationalism were strictly forbidden.

French directors and artists who refused to comply with censorship often went underground or sought ways to incorporate subtle criticism into their works.

...those that contained liberal or subversive ideas were suppressed...

French art and literature, as artists and writers were forced to navigate the limitations imposed by German and Vichy authorities.

Official censorship aimed to suppress dissenting voices and promote themes aligned with Vichy’s nationalistic, conservative ideology.

As a result, works that celebrated traditional values, rural life, and family loyalty were encouraged, while those that contained liberal or subversive ideas were suppressed.

Books, plays, and exhibitions that could promote “undesirable” messages were either banned or altered to meet censorship requirements.

...a platform to challenge Vichy propaganda...

Many French authors responded to these constraints with silence or subtle subversion.

Writers like Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus used allegory and abstraction to discuss themes of resistance and existentialism in works such as Sartre’s Les Mouches (The Flies) and Camus’s L’Étranger (The Stranger).

These works, while not overtly political, resonated with the French public by addressing the moral ambiguities and choices faced by individuals under occupation.

Camus also worked clandestinely on Combat, the underground resistance newspaper, using it as a platform to challenge Vichy propaganda and call for solidarity against occupation forces.

...a form of silent rebellion...

The fine arts, particularly painting, were also impacted by the restrictions and cultural propaganda of the time.

Some artists, like Pablo Picasso, remained in France despite the challenges, refusing to display their works under Vichy and German regulations.

Others joined the Resistance or created works in private that subtly critiqued the occupiers.

Surrealism, a movement rooted in freedom of expression, became a form of silent rebellion against the rigidity imposed by Vichy, as artists turned to symbolism and dreamlike imagery to express themes of repression and resilience.

...risked dismissal or arrest...

Education under Vichy France was reoriented to fit the regime’s vision of a morally conservative, authoritarian society.

The school curricula were revised to emphasize the virtues of obedience, rural life, and the ideal of a unified, Christian France, while demonizing the previous French Republic as corrupt and weak.

History lessons glorified Pétain’s leadership and cast him as a heroic, paternal figure guiding France through its difficulties.

Teachers who showed resistance to these changes risked dismissal or arrest, and students were encouraged to embrace Vichy’s principles, such as loyalty to family, nation, and the rejection of democratic values.

...and harbor distrust toward liberal or leftist ideas...

The Vichy government also established youth organizations similar to Germany’s Hitler Youth. The Chantiers de la Jeunesse, for instance, was a youth labor program that instilled Vichy-approved values and discipline in young men.

Through these programs, the government aimed to mold the next generation of French citizens into obedient, patriotic subjects who would support Vichy ideals and harbor distrust toward liberal or leftist ideas.

These indoctrination efforts created divisions among French youth, as some rejected the teachings and joined the Resistance, while others absorbed and internalized the Vichy perspective.

...found ways to communicate subversive messages...

Despite the extensive propaganda efforts, resistance to cultural manipulation remained strong.

The underground press became a powerful tool for countering German and Vichy narratives, with newspapers like Combat, Franc-Tireur, and Libération providing factual information and promoting solidarity against occupation.

Artists, musicians, and writers found ways to communicate subversive messages, employing coded language, symbolism, and irony to express dissent without directly challenging the authorities.

Jazz, for example, was popular among the youth as a subtle form of rebellion, as it represented American culture, which was officially condemned by the Vichy regime.

Underground art exhibitions, poetry readings, and clandestine performances became forums for the French to express a sense of defiance and retain their cultural identity.

...a means of coping and a subtle resistance...

In summary, the Nazi and Vichy regimes exerted control over nearly every cultural avenue in occupied France, but these efforts were met with resilience and quiet defiance.

Despite censorship, French culture adapted and found subversive ways to survive, becoming both a means of coping and a subtle resistance to occupation.

Through creativity, symbolism, and underground networks, the French demonstrated their refusal to be fully subdued by propaganda, retaining the cultural identity that would later shape post-war France.

The Jewish Experience and Anti-Semitic Policies

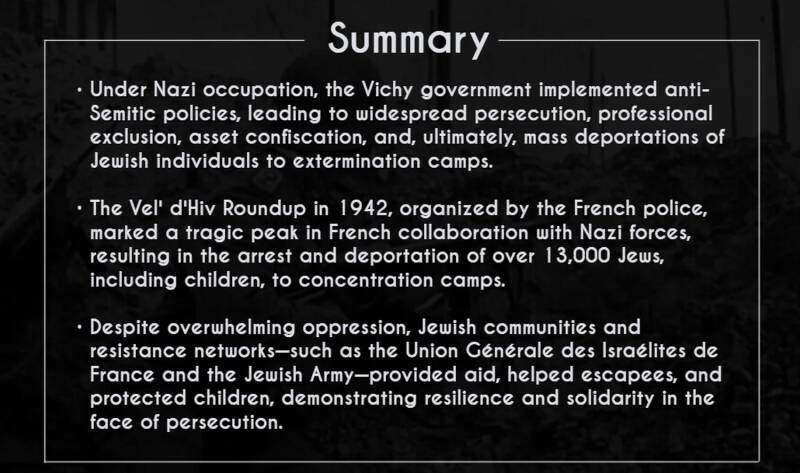

The Jewish experience in occupied France was marked by persecution, exclusion, and the horrors of deportation under both German and Vichy anti-Semitic policies.

From the early days of occupation, Jews in France were targeted with restrictive legislation, discriminatory actions, and, ultimately, mass deportations to extermination camps.

The Vichy government played an active role in the persecution, going beyond German demands to implement harsh anti-Semitic laws and oversee the arrest and deportation of Jews.

This section examines the evolution of anti-Semitic policies, key events such as the Vel’ d’Hiv Roundup, the collaboration between Vichy and Nazi forces in the Final Solution, and the acts of resilience and resistance by Jewish communities.

...marking a disturbing shift toward an official state policy...

A postcard depicting a crudely, stereotyped Jew enacting its global domination. This type of persistent antisemitic propaganda aimed at dehumanising the Jewish population in the eyes of the French population.

https://www.theholocaustexplained.org/life-in-nazi-occupied-europe/occupation-case-studies/france/

Soon after France’s defeat, the Vichy regime began implementing anti-Semitic measures. Marshal Philippe Pétain and his government, aiming to restore “traditional” French values, believed in the ideological alignment of France with Nazi anti-Semitic views, portraying Jews as foreign and detrimental to the purity of French society.

The first Statut des Juifs (Jewish Statute) was issued on October 3, 1940, without any demand from the German occupiers, marking a disturbing shift toward an official state policy of exclusion.

This statute stripped Jews of French citizenship if they were naturalized after 1927, barred them from certain professions (such as education, journalism, and civil service), and imposed restrictions on their participation in the economy.

Vichy enacted a second statute in June 1941 that further limited Jewish involvement in both public and private life.

In German occupied Paris, an elderly woman walks along the street wearing the yellow star that Nazis forced Jews to wear.

https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/color-photos-of-occupied-paris-zucca/

André Zucca / Bibliothèque historique de la ville de Paris / Wikimedia Commons / TopFoto / Captions from Daily Mail UK)

...aligning Vichy’s ideology with the Nazi regime...

In addition to professional exclusion, Jewish citizens faced social isolation and harassment. Businesses owned by Jews were identified, confiscated, or transferred to non-Jewish management, a process known as “Aryanization,” which was enforced by Vichy authorities.

Jews were also required to register their assets, making it easier for the state to seize their property. These laws did not come solely from Nazi mandates; rather, they were enacted with the explicit intention of appeasing the German occupiers and aligning Vichy’s ideology with the Nazi regime.

However, this compliance evolved into active participation, as Vichy administrators carried out these measures with zeal and often extended them beyond what German authorities required.

Front page of the newspaper Le Matin, dated 19th October 1940 announcing anti-semitic laws.

...overcrowded, unsanitary conditions...

One of the darkest chapters in French history is the Rafle du Vel’ d’Hiv (Vel’ d’Hiv Roundup), which took place on July 16–17, 1942.

In an unprecedented operation organized by French police in cooperation with German forces, over 13,000 Jewish men, women, and children in Paris were arrested and detained at the Vélodrome d’Hiver, a sports stadium in Paris.

Held in overcrowded, unsanitary conditions, these detainees were then deported to internment camps such as Drancy, Pithiviers, and Beaune-la-Rolande before being transported to Auschwitz and other extermination camps in the east.

...endure brutal conditions...

The Vel’ d’Hiv Roundup marked the first large-scale deportation of Jewish families, and it was notable for the extent of French complicity.

The French police, under orders from René Bousquet, head of the Vichy police, played a central role in organizing and carrying out the arrests.

While Nazi authorities initially focused on deporting foreign Jews, Vichy’s willingness to deport French-born Jews reflected the state’s commitment to a policy of anti-Semitic “purification.”

Families were torn apart, as children were separated from their parents and many were left to endure brutal conditions alone before being sent to their deaths.

By the end of the occupation, an estimated 76,000 Jews had been deported from France, of whom only around 2,500 survived the Holocaust.

This notice, issued by the local government in the Dordogne region of southern France on the 29th June 1942, required all Jews who had entered France since the 1st January 1936, to register with the local Police. This was designed to make it easier for the authorities to arrest foreign Jews.

https://www.theholocaustexplained.org/life-in-nazi-occupied-europe/occupation-case-studies/france/

An order by Wilhelm Keitel, Chief of the German Armed Forces High Command, ordering the seizure of Jewish property in occupied France. In occupied France, the Vichy regime, collaborating with Nazi authorities, implemented Aryanization laws to seize Jewish property. Businesses, homes, and assets were confiscated, often transferred to non-Jewish owners. This state-sanctioned plundering left many Jewish families destitute, further enabling their persecution and deportation.

https://www.theholocaustexplained.org/life-in-nazi-occupied-europe/occupation-case-studies/france/

...the active measures they took in arresting and deporting Jews...

The Vichy government’s collaboration in the Nazi Final Solution has remained one of the most contentious aspects of its legacy.

While some Vichy officials claimed their actions were meant to prevent worse consequences from direct German control, this argument does not account for the active measures they took in arresting and deporting Jews.

The French police and administrators at all levels facilitated the identification, registration, and transfer of Jewish people to internment camps, many of which were controlled by French authorities until deportations to the east.

...agreed to deport any Jews requested by the Nazis...

The collaboration in the Holocaust represented an intersection of ideological anti-Semitism and a pragmatic willingness to work within Nazi frameworks to maintain a semblance of autonomy.

Vichy leaders, particularly Pierre Laval and Louis Darquier de Pellepoix, who headed the General Commission for Jewish Affairs, rationalized the mass arrests and deportations by arguing that it was preferable to target foreign Jews to spare French-born Jews.

However, by 1943, this distinction became meaningless, as Vichy agreed to deport any Jews requested by the Nazis, further entrenching their involvement in the Final Solution.

...also provided material aid, helped children escape...

Despite the overwhelming oppression, many Jews in France resisted and found ways to survive.

Jewish organizations like the Union Générale des Israélites de France (UGIF) were initially created under Vichy orders to manage Jewish affairs, but they also provided material aid, helped children escape, and communicated with underground resistance networks.

As the danger increased, Jewish resistance groups emerged, many of them formed by young people who saw survival as a form of defiance.

The Jewish Army (Armée Juive) was one such organization, established to help Jews flee to unoccupied zones and protect families from deportation.

...learned to live in silence to avoid detection...

The Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants (OSE) was another critical group that helped smuggle Jewish children to safety.

OSE volunteers and other resistance workers transported children to Switzerland or to rural areas in southern France, where they were hidden by sympathetic French families, Catholic convents, and Protestant communities in regions such as Le Chambon-sur-Lignon.

These hidden children often assumed false identities and learned to live in silence to avoid detection.

Many communities risked their lives to shelter Jews, a testament to the solidarity that existed among parts of the French population despite the pervasive dangers of collaboration.

...clandestine networks for escape...

Individual acts of bravery by Jews and non-Jews alike became a lifeline for many families.

The Mouvement des Jeunes Sionistes (Zionist Youth Movement) in southern France organized clandestine networks for escape, while other Jewish resisters joined broader networks like the Franc-Tireurs et Partisans – Main-d’Oeuvre Immigrée (FTP-MOI), which carried out armed resistance against German forces.

The resilience shown by Jewish communities and their allies represented a powerful statement of survival and courage in the face of systemic persecution.

...unspeakable suffering for Jewish families...

The Jewish experience in occupied France underscores the extremes of human cruelty and bravery under oppression.

The collaboration of the Vichy government with Nazi policies led to unspeakable suffering for Jewish families, revealing a harrowing legacy that France has grappled with for decades.

Yet the acts of resilience, defiance, and solidarity within Jewish communities and their supporters offer a powerful reminder of the strength of humanity under even the most dire circumstances.

Liberation of France and the Aftermath

The liberation of France marked the culmination of four brutal years of occupation and collaboration, ushering in a period of jubilation, justice, and rebuilding that would shape the country’s post-war identity.

From the Allied invasion of Normandy in June 1944 to the liberation of Paris and other cities in August, the road to freedom was paved with both triumph and complex challenges.

The immediate aftermath of liberation brought about widespread reprisals against collaborators, efforts to rebuild national unity, and the difficult work of addressing the scars left by occupation.

This section examines the liberation efforts, the purge of collaborators, the process of reintegration and reconstruction, and the struggle for national memory and reconciliation.

...months of meticulous preparation...

The liberation of France began with the Allied invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944, known as D-Day.

Under the command of General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Allied forces launched a massive amphibious assault on the Normandy beaches, deploying over 150,000 troops.

This assault marked the beginning of Operation Overlord, a carefully planned campaign to break through German defences and liberate Western Europe.

The success of the Normandy landings hinged on months of meticulous preparation, intelligence gathering, and resistance activities that sabotaged German supply lines and disrupted communications.

One of the most iconic photographs of the Second World War: American soldiers wade ashore on Omaha Beach, the first step in the eventual liberation of France from Nazi rule.

Marina Amaral

...engaging in guerrilla warfare...

After securing a foothold in Normandy, Allied forces pushed inland, encountering fierce German resistance in cities like Caen and Saint-Lô.

The French Resistance played a crucial role by providing intelligence on German troop movements, sabotaging infrastructure, and engaging in guerrilla warfare to weaken the occupiers’ defences.

The momentum of the Allied advance eventually led to the liberation of Paris on the 25th August, 1944.

General Charles de Gaulle and the Free French Forces entered the city amidst celebrations and parades, while the remnants of German forces retreated.

The liberation of Paris was a symbolic victory, marking the end of occupation in France and setting the stage for the final Allied push into Germany.

Magazines scattered among the rubble of the heavily bombed town of Saint-Lô, Normandy, France, summer 1944.

https://www.life.com/history/before-and-after-d-day-color-photos-from-england-and-france/

Frank Scherschel; Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Crowds of French patriots line the Champs Elysees to view Free French tanks and half tracks of General Leclerc's 2nd Armored Division passes through the Arc du Triomphe, after Paris was liberated on the 25th August 1944. Among the crowd can be seen banners in support of Charles de Gaulle.

...punished in various ways...

A French soldier of the Leclerc Division riding a tank is greeted by Parisians on the 25th August 1944 in front of the city hall.

AFP PHOTO (French Press Agency)

With liberation came a wave of reprisals against those who had collaborated with the German occupiers and the Vichy regime.

Known as the Épuration légale (Legal Purge), this period saw tens of thousands of individuals, known as collaborateurs, arrested, tried, and often punished in various ways.

The desire for justice was strong, as the years of oppression had left the public eager to hold accountable those who had betrayed the nation, contributed to the Holocaust, or persecuted members of the Resistance.

However, this purge was also marked by inconsistencies and excesses, reflecting the intense emotions and complex moral landscape of post-liberation France.

A woman being shaved by civilians to publicly mark her as a collaborator, 1944. After liberation, French women accused of collaborating with Germans faced public shaming, including the symbolic tonte des femmes (head-shaving). Paraded through towns, they were often humiliated as "horizontal collaborators" amid intense post-war reprisals.

https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/french-female-collaborator-punished-head-shaved-publicly-mark-1944/

In addition to formal trials, a parallel, extrajudicial purge known as the Épuration sauvage (Wild Purge) took place immediately after liberation.

This wave of revenge often involved summary executions, public shaming, and violent reprisals against suspected collaborators, especially in areas where Nazi occupation had been particularly harsh.

Some collaborators were paraded through the streets, humiliated, and subjected to brutal “punishments.”

Women accused of collaborating with German soldiers were subjected to tonte des femmes (head-shaving) in public, a form of public humiliation intended to shame them as “horizontal collaborators.”

...was tried for treason and sentenced to death...

As the initial fervor subsided, formal judicial processes replaced these spontaneous acts of revenge.

Between 1944 and 1951, tens of thousands of individuals were prosecuted in official courts, including high-profile figures such as Philippe Pétain, the leader of the Vichy government. Pétain was tried for treason and sentenced to death, although de Gaulle later commuted his sentence to life imprisonment.

Pierre Laval, Pétain’s head of government, was also convicted of treason and executed. Many collaborators received prison sentences, while some were stripped of civil rights and barred from holding public office.

The purge was complex and controversial, as not all collaborators faced equal treatment, and decisions about punishment often reflected the ambiguities and compromises made during occupation.

...left infrastructure, housing, and industry in dire need of repair...

With the liberation of France, the country faced the monumental task of rebuilding its war-torn economy, restoring political stability, and addressing the social divides left by the occupation.

The physical destruction caused by bombing raids, battles, and the economic strain of German exploitation left infrastructure, housing, and industry in dire need of repair.

The French government, led by de Gaulle’s provisional government, implemented initiatives to revitalize the economy, nationalize key industries, and provide employment opportunities to veterans and former resisters.

...communities had often been divided by the occupation...

The social reintegration of France was complicated by lingering divisions over collaboration and resistance.

Families, neighborhoods, and communities had often been divided by the occupation, with some members collaborating and others joining the Resistance.

Rebuilding a sense of national unity required not only legal reconciliation but also the fostering of mutual understanding and forgiveness among citizens.

Many resisters returned to their pre-war lives, while collaborators attempted to reintegrate into a society that remained wary of their actions during the occupation.

For some, returning to normalcy was nearly impossible, as the occupation left psychological scars and memories of betrayal that would endure for generations.

...distance itself from the authoritarian policies of Vichy...

Politically, the liberation marked the beginning of a new era in French governance. De Gaulle’s provisional government laid the foundation for the Fourth Republic, which was formally established in 1946.

Reforms included a renewed commitment to democratic values and social programs aimed at improving conditions for the working class.

The new government sought to distance itself from the authoritarian policies of Vichy, promoting a more egalitarian and inclusive France.

The state also invested in social security systems, education, and industrialization, laying the groundwork for post-war economic prosperity and modernization.

...largely ignored the reality of widespread collaboration...

The aftermath of liberation left France grappling with complex questions of memory, identity, and accountability.

The narrative of the Resistance became a central element of post-war French identity, symbolizing resilience, patriotism, and moral courage.

Charles de Gaulle and his government encouraged this “resistance myth,” presenting the majority of the French people as supportive of the Resistance and opposed to Nazi rule.

This narrative, while uplifting, largely ignored the reality of widespread collaboration and the difficult moral choices faced by ordinary citizens under occupation.

...exploring the moral ambiguities...

In the decades following liberation, France gradually confronted these more challenging aspects of its wartime history.

Historians, writers, and filmmakers began exploring the moral ambiguities and varied responses of French citizens, revealing that collaboration was more prevalent and the Resistance less universal than initially portrayed.

Works like Robert Paxton’s *Vichy France: Old Guard and New Order* challenged the official narrative, prompting public debate and encouraging a more nuanced understanding of France’s wartime experience.

Additionally, the efforts of Jewish survivors and their descendants ensured that the memory of the Holocaust and Vichy’s complicity in anti-Semitic policies became integral to France’s collective memory.

...fostering a sense of shared memory...

The struggle for historical reconciliation has continued into the present day. Official apologies from the French government, such as President Jacques Chirac’s 1995 acknowledgment of France’s role in the Holocaust, have sought to address past injustices and promote healing.

Memorials, museums, and annual commemorations now serve as reminders of the occupation’s impact, fostering a sense of shared memory that includes both the heroism of the Resistance and the complexities of collaboration.

The liberation and its aftermath set France on a path of renewal, though one fraught with difficult questions of justice, unity, and identity. The experiences of liberation, purge, reconstruction, and reconciliation illustrate the depth of France’s struggle to come to terms with its wartime past and to build a society rooted in the values of democracy, resilience, and remembrance.

Conclusion

The occupation of France during The Second World War remains a profound chapter in both French history and the broader narrative of the conflict.

Lasting from 1940 to 1944, this period was characterized by a complex interplay of oppression, collaboration, and resistance.

The swift fall of France to German forces and the establishment of the Vichy regime illustrated the vulnerabilities of the nation and the moral ambiguities faced by its leaders and citizens.

While some collaborated with the occupiers for various reasons, including political ideology or personal gain, many others actively resisted the Nazi regime, displaying immense courage in the face of adversity.

...this tumultuous time fueled a national reckoning...

The legacy of this occupation profoundly impacted French society and its post-war identity.