A call for help

By May 1940, the Germans had seized control of Europe as their ground forces breached Allied defences with lightning-fast "Blitzkrieg" manoeuvres that inflicted devastation and mayhem. As the strategic situation shifted, Allied soldiers dispersed, routes were clogged with scared refugees, and the Allied command struggled to keep up.

Despite valiant efforts to stem the flow, the British and French armies were pushed further back, until the majority of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and a sizable number of French soldiers were besieged at Dunkirk.

The Royal Navy was tasked with organizing the evacuation, which was known as Operation Dynamo. The navy had a limited number of ships available for the operation, and it quickly became clear that additional vessels would be needed. The call went out to civilian boat owners, who were asked to volunteer their boats for the evacuation.

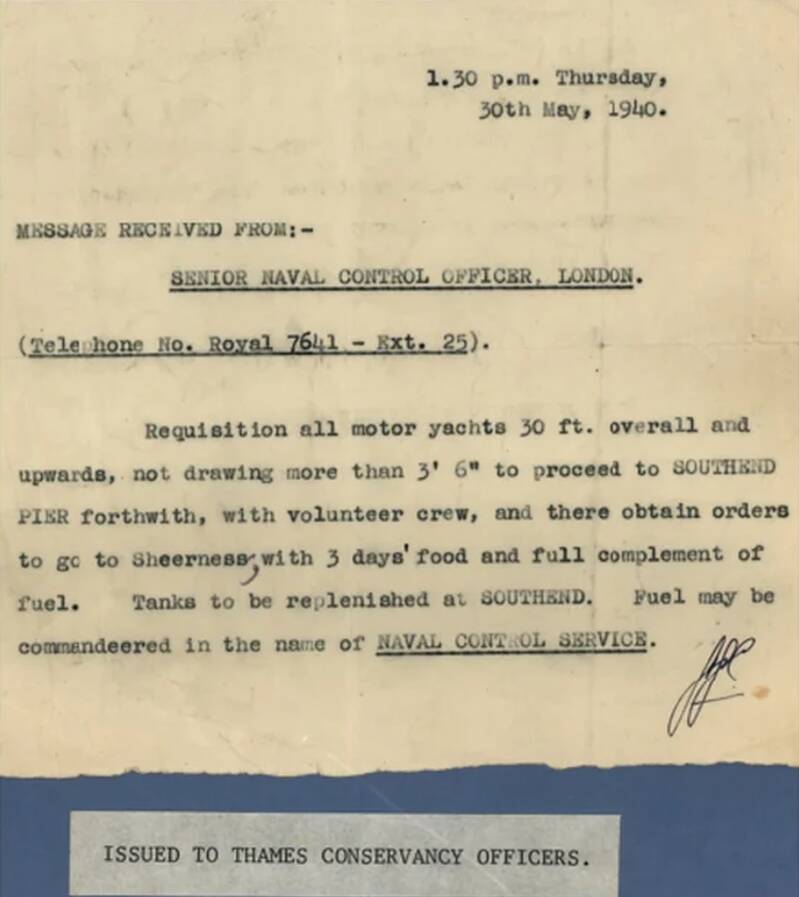

The naval order which started it all: The requisition of 'all motor yachts 30 ft overall and upwards'....

DUNKIRK 1940 | The Association of Dunkirk Little Ships (adls.org.uk)

British Expeditionary Forces queue up on the beach at Dunkirk to await evacuation.

The Miracle of Dunkirk in rare pictures, 1940 - Rare Historical Photos

...They were manned by officers, ratings, and seasoned volunteers from the Royal Navy....

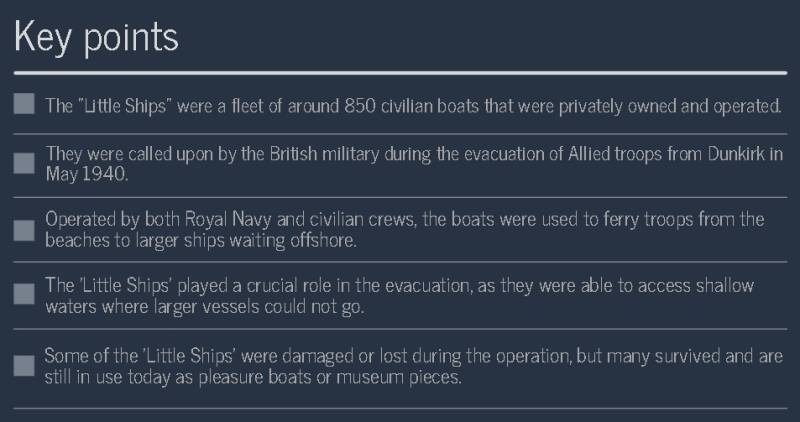

The response was overwhelming. Boat owners from all over the south and east coasts of England offered their boats, ranging from pleasure yachts to fishing boats. The Royal Navy began to requisition these boats, which became known as the 'Little Ships', and assign them to various tasks in the operation.

The boats were transported to Ramsgate for fuelling, seaworthiness testing, and departure for Dunkirk. They were manned by officers, ratings, and seasoned volunteers from the Royal Navy. Apart from fishermen and one or two other owners, very few people skippered their own boats.

The organization of the 'Little Ships' was a complex task, as they were owned by private individuals and had varying capabilities and capacities. The Royal Navy assigned them to different areas of the beaches and designated specific tasks for each boat. Some were used to ferry soldiers from the shore to larger ships waiting offshore, while others were used to transport troops to the beaches or to supply them with food and water.

Some of the civilian vessels - the 'Little Ships' - being gathered on the Thames before departing to Dunkirk,

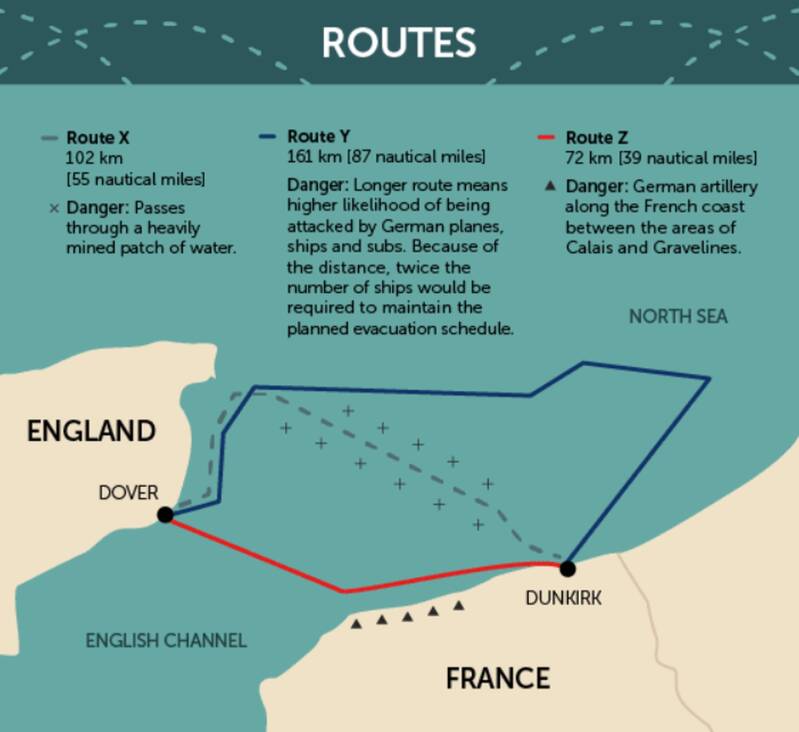

The 'Little Ships' had three different routes to the Dunkirk perimeter in France: X , Y and Z - Each route had its own pros' and cons'.

In order to ensure the safety of the boats and their crews, the navy established a convoy system for the 'little ships'. Groups of boats were assigned to travel together, with larger naval vessels acting as escorts and providing protection from enemy fire.

...some of the crews had no experience of operating in a war zone...

The convoys had to navigate through a dangerous minefield, and the boats had to be careful to avoid enemy fire from the air and sea.

The lead-up to the use of the 'little ships' was chaotic and confusing. The boat owners were not given clear instructions on what was expected of them, and there was a lack of communication between the navy and the civilian volunteers. Many of the boats were not properly equipped for the task, and some of the crews had no experience of operating in a war zone.

The evacuation at Dunkirk -and the role of the 'Little Ships' - was reported extensively in the media, as the drama played out over the course of a few days.

The evacuation

The 'little ships' played a notable role during Operation Dynamo and their contribution is still remembered with great admiration.

The 'little ships' were civilian boats, ranging from pleasure yachts to fishing boats, which were commandeered by the British navy for the purpose of evacuating soldiers from the beaches of Dunkirk.

They were called 'little ships' because they were small compared to the large naval vessels that were also involved in the operation.

At the time, there were over 700 boats of various sizes that were requisitioned by the British navy. These boats were able to get close to the beaches and take on board soldiers who were stranded there.

Troops wade through the sea toward a rescue boat.

Royston Leonard/mediadrumworld

The 'little ships' were particularly effective in rescuing soldiers from shallow waters where larger ships could not venture.

They were also able to get closer to the beaches due to their smaller size, and thus were able to load and unload soldiers more quickly.

Some of the 'little ships' were also equipped with machine guns and were able to provide cover fire for the soldiers on the beaches.

The 'Little Ships'

They represented a cross-section of civilian marine vessels in the United Kingdom: Fishing trawlers, cockle boats, yachts, lifeboats, paddle ferries, leisure cruisers, a fire tender, garbage barges, and ships operated by the Pickfords moving company were among them, representing the entire spectrum of nautical activity in the country.

Lord Collingwood and Lord St. Vincent served with Yorkshire Lass, Count Dracula, and Dumpling, all of whom had unusual and colourful nicknames.

British Expeditionary Forces wade out to one of the “little ships” aiding the evacuation.

The Miracle of Dunkirk in rare pictures, 1940 - Rare Historical Photos

...Despite being hit by enemy fire during her third trip to Dunkirk, she made it back to England safely...

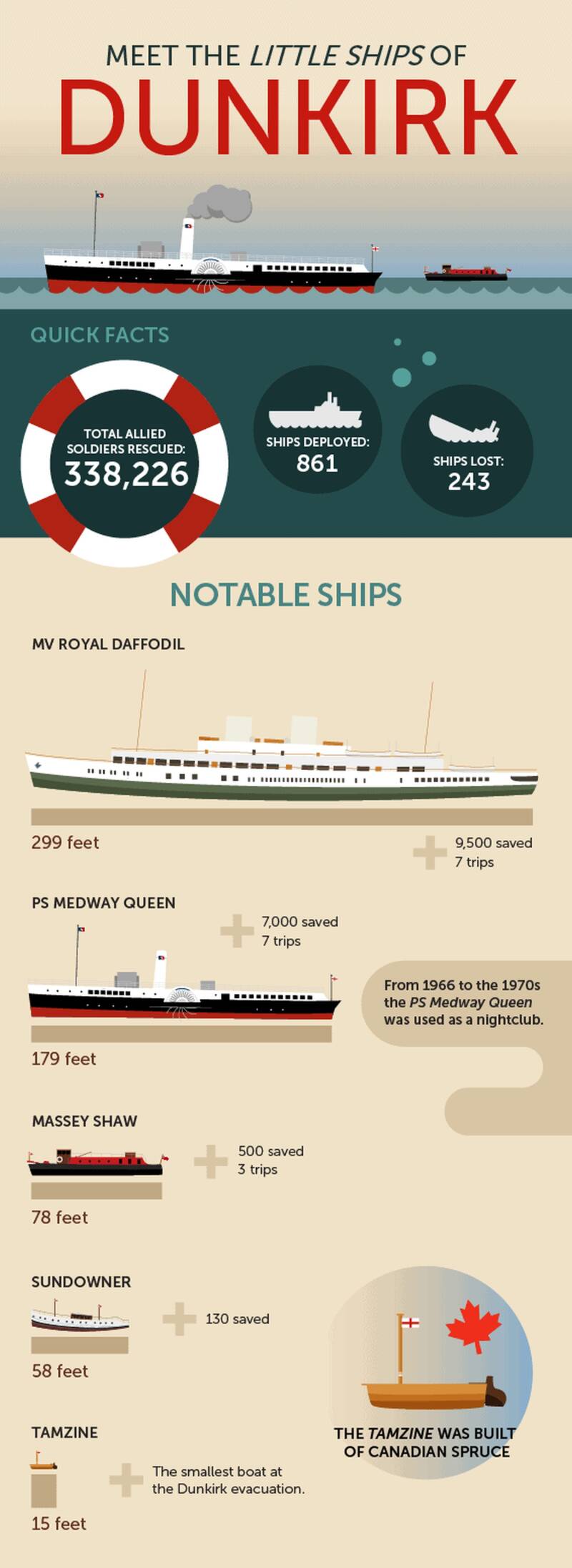

One of the most famous 'little ships' was the Thames paddle steamer, the Medway Queen. She made three trips to Dunkirk, evacuating over 7000 soldiers in total. The Medway Queen was built in 1924 and was used primarily as a pleasure boat. During the Second World War, she was requisitioned by the navy and fitted with guns to defend against enemy aircraft.

Despite being hit by enemy fire during her third trip to Dunkirk, she made it back to England safely with all her passengers earning herself the nickname "Heroine of Dunkirk". Restored and rededicated in 2013, she can now be visited at the Gillingham Pier in Kent.

Another notable 'little ship' was the 'Sundowner', a 50-foot motor cruiser owned by a private individual, Tom Sopwith. Sopwith was a famous aviator and aircraft designer, and he used his boat to rescue soldiers from the beaches of Dunkirk. The 'Sundowner' made several trips to Dunkirk, and Sopwith himself piloted the boat on one occasion. The 'Sundowner' managed to rescue 130 soldiers, despite coming under heavy fire from enemy aircraft.

The Sundowner (which celebrated its 100th birthday in 2012) is a motor yacht formerly owned by Charles Lightoller, the second officer of RMS Titanic and the most senior officer to survive her sinking in 1912. She participated in the Dunkirk evacuation as one of the "little ships" as well ..

The Bluebird of Chelsea was a luxury pleasure boat owned by Lord Wakefield, a prominent British businessman. The boat had a top speed of 15 knots and was used to ferry soldiers from the beaches to larger ships waiting offshore. Bluebird of Chelsea made two trips to Dunkirk and rescued a total of 130 soldiers although not without facing some challenges: after first refilling the fuel tanks with water, then fouling her screws on debris, she returned under tow.

The MV Royal Daffodil was requisitioned by the General Steam Navigation Company of London and eventually evacuated 7,461 service members from Dunkirk in five journeys between the 28th of May and the 2nd of June, including the French historian Marc Bloch, who served as a French army captain throughout the conflict.

This was the most people evacuated by a single passenger ship during the operation. Six German planes attacked her on the 2nd of June. One of them dropped a bomb through two of her decks and blew a hole below the water line, but despite taking a battering, she managed to limp back to port.

The Mary Jane was a fishing boat owned by John Lewis, a fisherman from Dover. The boat had a top speed of 7 knots and was used to ferry soldiers from the beaches to larger ships waiting offshore. Mary Jane made six trips to Dunkirk and rescued a total of 600 soldiers.

Elvin was a Thames barge that had been converted for use as a troop carrier. The boat had a capacity of 100 soldiers and was used to transport troops from the beaches to larger ships waiting offshore. Elvin made six trips to Dunkirk and rescued a total of 500 soldiers.

Three of the armada of 'little ships' which brought the men of the BEF from the shores in and around Dunkirk, to the safety of British warships and other vessels.

Imperial War Museum

...Endeavour made four trips to Dunkirk and rescued a total of 380 soldiers...

The Endeavour was a motor yacht owned by Thomas and Evelyn Penrose. The boat had a top speed of 12 knots and was used to ferry soldiers from the beaches to larger ships waiting offshore. Endeavour made four trips to Dunkirk and rescued a total of 380 soldiers.

The fishing boat Lady Gay was owned by Alfred Jenkins, a fisherman from Ramsgate. The boat had a top speed of 8 knots and was used to ferry soldiers from the beaches to larger ships waiting offshore. Lady Gay made two trips to Dunkirk and rescued a total of 120 soldiers.

Massey Shaw was a London-based fireboat which initially went to Dunkirk to help fight fires. It ended up making three trips across the channel rescuing over 500 troops, including 30 from the Emil de Champ, which had hit a mine.

At 14.7 feet (4.5 m) in length, the Tamzine was the smallest vessel to take part in the evacuation and now preserved by the Imperial War Museum.

Along with the flotilla of other Dunkirk 'Little Ships', The fireboat Massey Shaw is credited with saving over 500 troops from the beaches. Due to the relatively flat hull of Massey Shaw, she was able to get closer to the shore so that soldiers could wade out and climb aboard, to be ferried to the larger ships. Unfortunately, the Massey Shaw did not have a lot of space to accommodate people, however she was able to bring back over 100 troops directly to the UK during the evacuation.

The Lifeboats

During Operation Dynamo, boats from the Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI) also assisted with the evacuation.

Given their robust seaworthiness and ability to work in extreme conditions, they were a natural choice to take part in a large-scale evacuation.

Only the Ramsgate and Margate lifeboats were crewed by RNLI lifeboat crew. The other 17 lifeboats were used by the Navy but played an important part in the evacuation.

The following lifeboats saw action at Dunkirk during Operation Dynamo.

- On 30 May 1940, the Abdy Beauclerk and the Lucy Lavers, which served Aldeburgh in Sufflolk's No: 2 Station, were commandeered by the Royal Navy to assist in the Dunkirk evacuation. They remained there until 4 June 1940.

- Cecil and Lilian Philpott, a Watson-class lifeboat from Newhaven, Sussex evacuated 51 soldiers but was left high and dry on the beach for 4 hours until the next day when she resumed the evacuation.

- Charles Cooper Henderson, a Beach-class lifeboat from Dungeness, Kent was taken to Dunkirk with a crew of naval ratings. She got back to Dungeness but had sustained some damage.

Margate Coxswain Edward Parker with his sons James (left) and Edward. All three took part in the evacuation of Dunkirk in May 1940.

A C Robinson

...and also survived three enemy air attacks off Gravelines...

- Charles Dibdin, a Beach-class lifeboat from Walmer, Kent and Cyril and Lilian Bishop, a Self-righting-class lifeboat from Hastings, East Sussex also made the hazardous trip to Dunkirk.

- Edward Dresden, a Watson-class lifeboat from Clacton-on-Sea. Worked in Dunkirk harbour and was one of only a few lifeboats taken to Dunkirk by her own crew. M.E.D, a Watson-class lifeboat from Walton and Frinton station worked alongside her and also survived three enemy air attacks off Gravelines.

- Greater London, a Ramsgate-class lifeboat from Southend-on-Sea.

- Guide of Dunkirk, a new and unnamed Watson-class lifeboat at the time of the evacuation.

- Herbert Sturmey, a Self-righting-class lifeboat from Cadgwith, Cornwall.

- Jane Holland, a Self-righting-class lifeboat from Eastbourne, East Sussex. She was holed when a Motor Torpedo Boat rammed her and her engine failed after being machine-gunned by an aircraft. She was abandoned but later found adrift, towed back to Dover and repaired. She returned to service on the 5th of April 1941.

Ramsgate Coxswain Howard Knight who, along with his volunteer crew, helped evacuate soldiers from Dunkirk in May 1940.

...she evacuated over 500 men to the destroyer HMS Icarus...

- Louise Stephens, a Watson-class lifeboat from Gorleston and Great Yarmouth. She was taken to Dunkirk by a naval crew. She returned to England having suffered damage from German attacks.

- Lord Southborough, a Watson-class lifeboat from Margate, Kent. After arriving on the beaches for a second time, she evacuated over 500 men to the destroyer HMS Icarus.

- Mary Scott, a Norfolk and Suffolk-class lifeboat from Southwold. She was towed to Dunkirk by the paddle steamer Emperor of India together with two other small boats. Between them they took 160 men to their mother ship, then 50 to another transport vessel before her engine failed and could not be restarted. She was beached and abandoned at La Panne, east of Dunkirk. She eventually was refloated and returned to Southwold.

- Michael Stephens, a 46' Watson-class lifeboat from Lowestoft. She worked inside the harbour in Dunkirk and was rammed twice by German MTBs (motor torpedo boats), but she returned to Dover under her own power.

The Ramsgate class lifeboat, Prudential, which - crewed by RNLI volunteers, took part in Operation Dynamo.

...made three trips between Dover and Dunkirk....

- Prudential, a prototype Ramsgate-class lifeboat from Ramsgate, Kent. One of only a few boats taken to Dunkirk by her own crew, who collected 2,800 men from the beaches.

- Rosa Woodd and Phyliss Lunn, a Watson-class lifeboat from Shoreham Harbour. She made three trips between Dover and Dunkirk.

- Thomas Kirk Wright, a Surf-class lifeboat from Poole.

- Viscountess Wakefield, a Beach-class lifeboat from Hythe, Kent. She ran aground on the sands of La Panne, the only lifeboat to be sunk during the operation.

A morale booster

The 'little ships' also played a significant role in boosting morale both in Dunkirk and back in Britain. The sight of these small boats making their way across the English Channel to rescue soldiers captured the public imagination and was seen as a symbol of British determination in the face of adversity.

The boats themselves became famous, with some even being named after their owners or the towns they came from. The 'little ships' were also used in propaganda films, which showed the boats sailing across the Channel to the strains of patriotic music.

One of the 'little ships' returns to Britain laden with French troops. Operation Dynamo saw 338,000 troops rescued from the beaches of northern France between the 27th of May 27 and the 4th of June 1940.

Operating in shallow waters

In addition to their impact on morale, the 'little ships' were also instrumental in saving lives. Without them, many more soldiers would have been left stranded on the beaches of Dunkirk, where they would have been vulnerable to enemy attack.

The 'little ships' allowed the evacuation to continue around the clock, despite the fact that larger ships could not operate in the shallow waters close to the beaches. This meant that soldiers were being rescued constantly, and the number of lives saved was truly remarkable.

How much of impact did they actually make?

The contribution of the 'Little Ships' in Operation Dynamo, the evacuation of allied troops from Dunkirk in 1940, has been widely celebrated and praised as a heroic effort by civilian boat owners who came to the aid of their country.

However, some historians have argued that the impact of the 'Little Ships' in this operation has been overstated,

Some of the 'Little Ships' on the River Thames shortly before departing to take part in the evacuation of Allied troops at Dunkirk.

DUNKIRK 1940 | The Association of Dunkirk Little Ships (adls.org.uk)

The majority of troops were evacuated by larger vessels, including destroyers, minesweepers, and other naval vessels. These larger ships were able to evacuate thousands of troops at a time, while the 'little ships' could only take a few hundred each.

While the 'little ships' were useful for evacuating soldiers from shallow waters and getting close to the beaches, they were not as critical to the operation as the larger ships.

Additionally, the 'little ships' were not as numerous as many people believe. While over 700 boats were involved in the evacuation, only around 100 of these were actual 'Little Ships', with the majority being larger vessels.

The 'Little Ships' were also not all civilian-owned, as some were requisitioned by the government or owned by the navy.

The contribution of the 'little ships' to the overall number of troops evacuated was relatively small.

The Massey Shaw fireboat, with its London Fire Brigade volunteer crew, returning to its moorings at Lambeth HQ after assisting in the evacuation of the Allied forces from the beaches of Dunkirk during late May and the first days of June 1940.

While it is difficult to determine the exact number of soldiers rescued by the 'Little ships', estimates range from around 15,000 to 20,000. This is a small proportion of the total number of troops evacuated, which was over 338,000.

The role of the 'little ships' in Operation Dynamo has been romanticized and exaggerated over time. While their involvement was undoubtedly important and deserves recognition, some accounts have portrayed them as the saviours of the operation, while downplaying the efforts of the larger vessels and the bravery of the soldiers themselves.

The 'little ships' were only one part of a massive and complex operation that involved the coordinated efforts of the navy, air force, and ground troops.

One of the casualties: A ship sunk during the evacuation.

In conclusion, while the 'little ships' played a role in the evacuation of allied troops from Dunkirk, their impact has been overstated in some accounts. While their involvement was undoubtedly important and deserves recognition, they were only one part of a larger operation and their contribution to the overall success of the evacuation was relatively small.

It is important to recognize the bravery and sacrifices of all those involved in the operation, from the soldiers on the beaches to the crews of the larger naval vessels and the civilian boat owners who came to their aid.

Legacy

Regardless of the actual measurable impact the ‘Little ships’ had on Operation Dynamo; their impact can still be felt today. Many of the boats that took part in Operation Dynamo have been carefully preserved and are still in use. Some have even been lovingly restored to their former glory and are used for pleasure cruising. The 'little ships' also inspired a new generation of boat owners, who saw the bravery and determination of their crews.

July 1940, a month after the evacuation the 'Little Ships' are honoured by a review on the Thames.

However, even if much of their overall value is symbolic rather than literal, it is important to recognise the impact of their actions and the bravery of their crews. Churchill's "mosquito armada," did play its own, significant part in Operation Dynamo.

Many soldiers would not have returned home without them, and they paid a heavy price for doing so by enduring constant Luftwaffe attacks, needing to navigate minefields, swift tides, dense fog, and waters strewn with ever-more wrecks.

Over 100 people were lost crewing the ‘Little Ships’, many of whom were unidentified. The ‘Little Ships’ have a rightful place in history.

Some of the original 'Little Ships' which took part in the 75th anniversary of Operation Dynamo celebrations in 2015.

Dunkirk Little Ships anniversary celebrations - London's Royal Docks (londonsroyaldocks.com)

Further reading

Sources:

https://www.vintag.es/2017/08/pictures-of-dunkirk-little-ships-and.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Little_Ships_of_Dunkirk

https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/miracle-dunkirk-pictures-1940/

https://rnli.org/about-us/our-history/timeline/1940-dunkirk-little-ships

https://www.adls.org.uk/?_sm_au_=iVVtMj1ttJFF2nZk

http://londonsroyaldocks.com/dunkirk-little-ships-anniversary-celebrations/

https://masseyshaw.org/about/history/#wwii-blitz

Hugh Sebag-Montefiore, "Dunkirk: Fight to the Last Man" (2007)

Alistair Horne, "To Lose a Battle: France 1940" (2007)

Walter Lord, "The Miracle of Dunkirk: The True Story of Operation Dynamo" (2017)

Sean Longden, “Dunkirk: The Men They Left Behind.” (2009)