A reluctant participant

For much the First World War, Greece was neutral, more concerned with its own issues. In the early part of the century, it had seen much expansion so that by 1913, it was almost double its original size. However, this led to tensions with Bulgaria and the still powerful Ottoman Empire. Additionally, the country itself was split into two opposing factions regarding whether Greece should enter the First World War. Such was the split that Greece had two governments: A royalist pro-Central Powers one in Athens and a Venizelist pro-Allied powers one in Thessaloniki (named after the prominent statesman and leader of the Greek Liberation Movement, Eleftherios Venizelos.)

However, the two governments were eventually united in 1917, when Greece officially entered the war on the side of the Allied powers.

Eleftherios Venizelos (1864 - 1936), Greek statesman and leader of the Greek national liberation movement.

Genocide and upheaval

In the aftermath of the First World War, Greece continued to attempt to expand into areas of Asia which had large amounts of native Greeks. This resulted in the Greco-Turkish war of 1919-1922 in which Greece found itself on the losing side. This defeat resulted in large numbers of ethnic Greeks in the region of Anatolia (which was partially under Turkish control) being forced to flee. This was linked to ongoing Greek genocide which had been occurring since 1914 and in which large numbers of ethnic Greeks living in Anatolia (along with Assyrians and Armenians) found themselves being persecuted (with several hundred thousand being killed) and forced to escape the area. This exodus was permanent and expanded upon with further population movements as part of the Treaty of Lausanne which ended the war.

The next few years saw Greece trying to cope with this sudden influx of 1.5 million ethnic Greeks into its borders (Greece is a relatively small country covering 130,199 km2), many of whom could not speak the language or were simply unfamiliar with Greek culture and traditions.

Newspaper headlines reporting on the genocide.

The Second Hellenic Republic

Due to the catastrophic events of the genocide, the monarchy was abolished after a referendum on 25th March 1924 which saw 69.9% in favour of a republic and 30.1% in favour of the monarchy, and so the Second Hellenic Republic thus was formed. The new republic was fragile though and within the first year of its existence, there was a coup led by General Theodoros Pangalos, who surprisingly received a vote of confidence from parliament (he received 185 out of a possible 208 votes) and was soon sworn in as Prime Minister.

Shortly afterwards in 1925, a border dispute with Bulgaria (the ‘War of the Dog’) led to Pangalos ordering an invasion of Bulgaria which led to a brief, but violent war, and which ultimately ended with Greece being held responsible by the League of Nations and ordered to pay the equivalent of £2.7 million in compensation. Pangalos continued to impose his rule and increasingly persecuted opponents, suppressing, and exiling large number of communists.

General Theodoros Pangalos

The fall of Pangalos

However, many were critical of Pangalos. He was accused of conceding too many rights to Yugoslavs regarding trade and allowing Greece to be dragged into the unnecessary border conflict with Bulgaria was also a mistake, given how it damaged Greece’s international relations. Some of his other decisions were controversial too. On 30 November 1925 he passed a law which dictated the length of women’s skirts (they had to be no more than 30cm above the ground when out in public)!

Many of his former allies started to plot against him and on 29 August 1926, another coup occurred and the brief dictatorial reign of Pangalos came to an end, with him being sentenced to two years in prison.

Policeman checking skirt lengths during Pangalos's time in power.

End of the republic

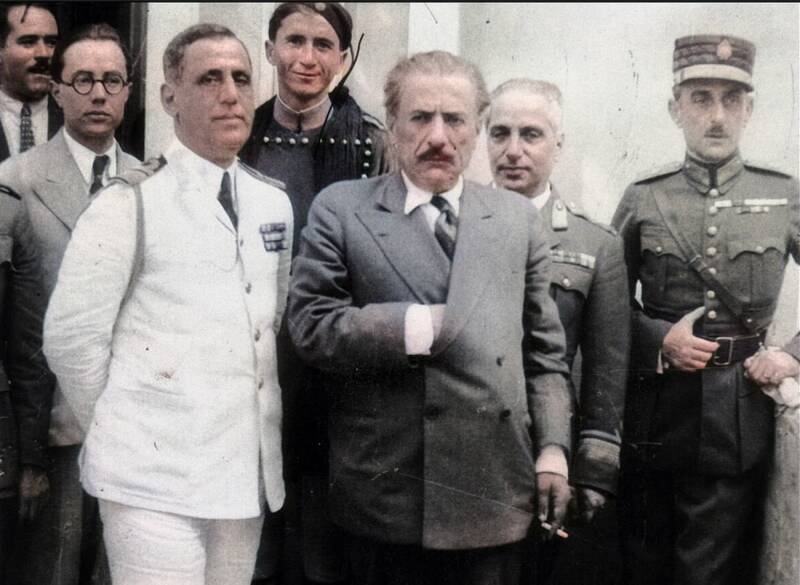

From 1928 until 1933, the Second Hellenic Republic initially saw a period of relative calm and stability which was unfortunately interrupted by the Great Depression, the effects of which were being felt across Europe. Political instability became increasingly problematic and the prospect of returning Greece to a monarchy became attractive to more and more people. Matters came to a head in March 1935 when, after a series of upheavals and power shifts, General Georgios Kondylis declared himself regent, forced President Zaimis to resign and abolished the republic.

To further support his claims, a heavily rigged plebiscite was held in which an implausible 98% of the population supported the return of the monarchy, which took place when King George II returned to Athens, the capital of Greece, on 23 November 1935, with Kondylis serving as his Prime Minister.

Prime Minister Georgios Kondylis (centre), flanked by the heads of the Greek armed forces, one day after the overthrow of the civilian government and the abolition of the Second Hellenic Republic, Oct 1935.

The rise of Metaxas

Kondylis himself did not last long as Prime Minister. He had become increasingly fascist in his outlook – admiring Mussolini’s Italy, and was increasingly arguing with the King (who had never forgotten Konylis’s hand in his earlier exile) – which led to Kondylis resigning and dying shortly afterwards of a heart attack on 1st February 1936.

He was succeeded by Konstantinos Demertzis who lasted only a few months as Prime Minister before he too – died of a heart attack.

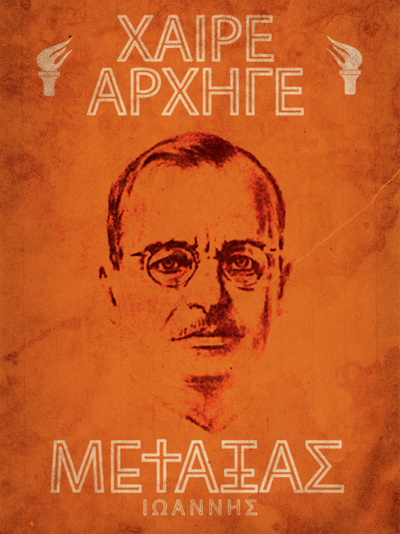

Next in line - the third Prime Minister in the same year - was Ioannis Metaxas – a former military officer who was favoured by the King as a dedicated monarchist. He bceame leader of Greece in 13 April 1936

However, Metaxas was not universally popular, and his appointment caused a wave of strikes across Greece with a general strike being called countrywide on 9th May. In response, Metaxas used this as an excuse to declare a state of emergency of 4th August 1936 – putting them blame of a general communist threat – and dissolved parliament permanently and suspended or restricted various civil liberties. This new coup became known as the “4th of August Regime” with Metaxas now an authoritarian ruler. State propaganda portrayed Metaxas as a "Saviour of the Nation", bringing unity to a divided country.

A different type of dictator?

Although a ‘far-right’ leader, Metaxas demonstrated notable differences from other ‘far-right’ leaders in Europe. He was generally pro-Jewish and tolerant of religious minorities, he lacked an inherent, ingrained and dedicated political base of movement (unlike Hitler and the Nazi’s or Mussolini’s Blackshirts) and he refrained from the usual far-right penchant for commissioning architecture or monuments to glorify his rule. Some consider it closer in ideology to Franco’s Spain, than Nazi Germany or Fascist Italy. Furthermore, despite it’s far-right learnings, Greece remained on good terms with Great Britain and ultimately did not join the Axis powers.

Greek Soldiers celebrating orthodox Easter in 1930.

The Metaxas regime sought to comprehensively change Greece, and therefore instituted controls on Greek society, politics, language, and the economy. It censored the media, banned political parties, and prohibited strikes. It also had its own version of the Gestapo (Nazi Germanies secret police), the Asfaleia – it’s main aim to maintain public order. The chief of the Asfaleia, Maniadakis, even forged close links with the head of the Gestapo, Henrich Himmler.

Greece in the 1920's and 1930's

Repression and persecution

The regime even went as far as to ban certain types of music and even instruments – Greek stringed instruments the baglamas and bouzouki were forbidden due to the ‘eastern’ style of musical sound they produced. Instead, a huge promotion of traditional Greek music took place instead. Additionally, certain traditions that had been introduced by outside cultures – such as Hashish dens - were also targeted and banned.

The regime – as per usual with far-right governments – turned its attention to the communists and leftists who soon found themselves being arrested and jailed or even exiled for their political beliefs – about 15,000 in total. The Greek Communist Party (KKE) was outlawed and forced to go underground although it managed to maintain its existence throughout the duration of the Metaxas regime.

However, despite its harsh measures, the Metaxas regime rarely resorted to murdering its opponents, instead preferring to exile those not in favour to one of the multitudes of tiny, Greek islands that dotted the Adriatic Sea. There is certainly no evidence to suggest any incidents of mass murder which frequently occurred in other totalitarian regimes. And although strongly Nationalist, the regime was tolerant of Greek Jews and revoked many of the antisemitic laws set in place by previous administrations.

Propaganda posters from during the Metaxas regime. Nothing at all sinister about the top left one.....

The end of the regime

Despite the efforts of the Metaxas regime, events outside Greece’s borders were to lead to its eventual downfall. Although Metaxas was pro-German, Greece had traditionally relied on Great Britain to support it in the event of conflict – mainly due to its naval power in the Mediterranean Sea. Greece was also facing pressure from Mussolini’s Italy, who’s own territorial ambitions clashed with Greece’s. Metaxas attempted to keep Greece neutral, but increasing pressure from Italy led to an ultimatum, which in turn led to the Greco-Italian War.

Sources:

Wikipedia

https://pappaspost.com/pontic-greeks-genocide-remembrance/

https://www.flickr.com/photos/128098853@N04/

https://greekcitytimes.com/2020/11/30/1925-pangalos-law-womens-skirts/

(8) Greek Soldiers celebrating orthodox easter in 1930 colorized. : europe (reddit.com)

Christos Kaplanis

http://in2greece.com/english/historymyth/history/general/modern.htm