Targeting the Convoys

The first attempts to crush Britain

The Kanalkampf (Channel Fight) was the German term for the Luftwaffe's air operations over the English Channel against the British Royal Air Force (RAF) in July 1940.

During the Second World War, air operations over the Channel launched the Battle of Britain.

The Allies had been defeated in Western Europe and Scandinavia by the 25th of June.

Adolf Hitler issued Directive 16 to the Wehrmacht (German armed forces) on July 16, ordering preparations for an invasion of Britain under the codename Unternehmen Seelöwe (Operation Sea Lion).

A landing exercise wWith the "Führerweisung" No. 16 of 16. In July 1940, the Wehrmacht began intensive preparations for the company "Sea lion". On the sandy beaches of Sylt or the French Channel Coast (picture), German soldiers rehearsed the invasion of England. In this case, a landing raft consisting of several boats served as a floating transport for the field hit. On 16 July 1940, Hitler issued Directive 16, formally authorising preparations for Operation Seelöwe, the planned German invasion of Britain. The directive outlined a cross-Channel assault designed to secure a decisive victory, contingent upon achieving air and naval superiority. Responsibility fell upon the Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe to neutralise the Royal Navy and cripple Fighter Command. While meticulous in its ambition, the directive underestimated Britain’s resilience and the logistical complexities of an amphibious invasion, leaving Seelöwe fatally compromised from inception.

...Hitler stood at a crossroads....

Prelude

In the days following the French surrender in June 1940, Adolf Hitler stood at a crossroads.

With mainland Europe under his control, Britain remained defiant.

On 2 July, he concluded that the island could not be invaded until the Luftwaffe had secured air superiority.

The Kriegsmarine was too weak to challenge the Royal Navy alone, so the skies would have to be cleared of the RAF before Operation Sea Lion—the planned invasion of Britain—could proceed.

By 12 July, Hitler clarified his thinking: German air power would be the shield and sword of the invasion.

A directive followed on 16 July, outlining clear objectives for the Luftwaffe—defend the invasion fleet from air attacks, destroy British coastal defences, and crush any resistance by the British Army.

But a full-scale assault on the RAF was still weeks away.

German 'Fuhrer' Adolf Hitler. After France’s fall in June 1940, Hitler planned Britain’s invasion, requiring Luftwaffe air superiority to counter the Royal Navy. By mid-July, he ordered German air power to shield, strike, and weaken British defences.

https://www.reddit.com/r/HistoryPorn/comments/19vu7r/a_rare_color_photo_of_adolf_hitler_which_shows/

By mid-1940, Nazi Germany dominated Western and Central Europe. France had fallen in June, joining a long list of occupied nations including Poland, Norway, Denmark, Belgium, and the Netherlands. German troops and administrators enforced control, exploiting resources and suppressing resistance. In Vichy France, a collaborationist regime emerged, while occupied territories endured rationing, propaganda, and political repression. Across the continent, Britain now stood alone in defiance, its survival dependent on resisting Germany’s next move—the coming air assault.

...infrastructure across France and Belgium had been devastated...

Prior to the Battle of Britain, Germany invaded France and the Low Countries. Drawing of the invasion of the Netherlands by L.J. Jordaan, 1945.

https://www.annefrank.org/en/anne-frank/go-in-depth/german-invasion-netherlands/

Collection: Geheugen van Nederland / Atlas Van Stolk, Rotterdam/ artist: L.J. Jordaan.

In the meantime, the Luftwaffe undertook its third major redeployment in just two months.

After first surging into the Low Countries and then southern France, German Air Fleets now moved into northern France and Belgium, positioning themselves along the English Channel.

This expansion was not smooth.

The infrastructure across France and Belgium had been devastated by the recent fighting.

Railways, roads, bridges, and airfields were in disrepair.

The German Army was tasked with rebuilding bridges to supply forward bases, while the Luftwaffe took over abandoned Allied airfields, many of which lacked even the basics—electricity, running water, or suitable runways.

A German soldier looks over a destroyed French city during the Battle for France in 1940. The German invasion of France in 1940 left vast swathes of the nation’s infrastructure shattered. Retreating French forces and advancing Germans alike destroyed bridges, rail lines, and key transport hubs to hinder movement. Cities and towns along the front suffered heavy bombing, damaging roads, ports, and factories. Railways were torn up or rendered unusable, while airfields lay cratered and abandoned. This widespread destruction crippled France’s logistics, complicating both civilian recovery and the German military’s own post-conquest redeployment.

https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/the-battle-of-france-furor-teutonicus-gallic-debacle/

...shortages plagued frontline units...

Logistics became a nightmare. The Luftwaffe’s supply lines, already strained, began to buckle.

On the 8th July, only 20 of 84 railway tankers carrying aviation fuel reached the critical supply depot at Le Mans.

Fuel shortages plagued frontline units, and the Transportgruppen—tasked with keeping the Luftwaffe running—could barely supply their own squadrons.

Replacements and reinforcements were trickling in through Ergänzungsverbände (supplemental formations), but not quickly enough to restore full operational strength.

Messerschmitt Bf 109E1 1./Jagdgeschwader 51 'White 9' force landed France 1940. During the Battle of France (May–June 1940), the Luftwaffe secured air superiority but suffered significant attrition. German records indicate around 1,300 aircraft lost, including bombers, fighters, and reconnaissance planes, while hundreds more were damaged. Many veteran crews were killed or captured, weakening Germany’s long-term operational strength. Though the Luftwaffe supported the rapid Blitzkrieg effectively, these losses—especially among trained pilots—would strain resources and contribute to mounting difficulties during the subsequent Battle of Britain.

...momentum of conquest was slowed by complacency...

And while ground crews and junior officers struggled to prepare for the next phase, many of the senior Luftwaffe staff were enjoying the luxuries of victory.

Paris had fallen, and with it came celebration, promotions, and parades.

Hermann Göring, elevated to Reichsmarschall, basked in glory while vital preparations stagnated.

The momentum of conquest was slowed by complacency.

Nevertheless, the Luftwaffe slowly gathered its strength. As preparations limped forward, German aircraft began probing British defences across the Channel.

Reichsmarschall of the Luftwaffe, Hermann Göring.

Luftwaffe personal checking an Messerschmitt 109 fighter. Preparing for Kanalkampf placed enormous strain on Luftwaffe maintenance crews. Aircraft operating from hastily adapted French and Belgian airfields faced salt corrosion from Channel air, heavy dust from summer conditions, and constant wear from high sortie rates. Spare parts were often in short supply, forcing cannibalisation of damaged machines to keep others flying. Mechanics worked around the clock under pressure, yet maintaining serviceability across bombers and fighters proved a constant challenge, limiting operational strength during sustained convoy attacks.

...a bloody and costly prelude...

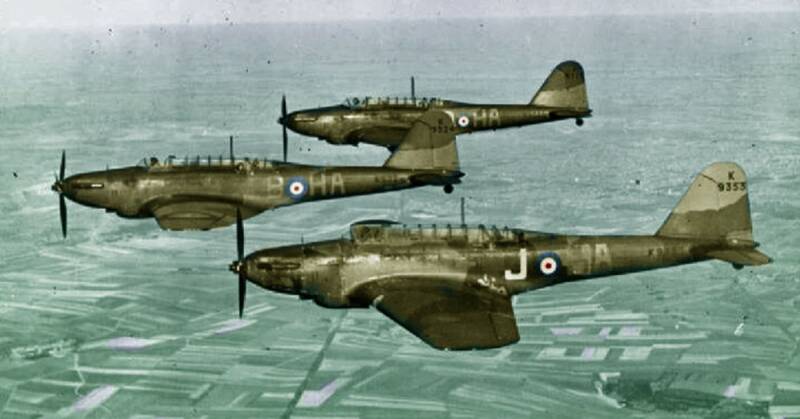

This phase, known as the Kanalkampf (Channel Battle), involved repeated attacks on merchant convoys and occasional dogfights with RAF fighters.

These skirmishes were intended to lure the RAF into combat, weaken their forces, and test Britain's resolve.

It was a bloody and costly prelude, but not yet the full fury of the Battle of Britain.

It would take forty long days after France’s fall before the Luftwaffe was ready to launch its main offensive.

The Kanalkampf marked the opening notes of an aerial symphony of war—a warning of the storm that was about to break over southern England.

Luftwaffe ME 109's in the skies over England. During Kanalkampf, the Messerschmitt Bf 109 proved both vital and vulnerable. Operating at the edge of its range when crossing the Channel, it had limited endurance—barely 20 minutes of combat time over southern England. While it provided essential escort for German bombers, forced withdrawals and fuel shortages often left the latter exposed. Many 109s crash-landed in France after running out of fuel, highlighting the aircraft’s logistical limitations despite its formidable performance in dogfights against Hurricanes and Spitfires.

German Preparations

In the summer of 1940, as the smoke of war settled over conquered France, the Luftwaffe turned its gaze toward Britain.

Yet, despite its triumphs on the continent, Germany’s mighty air force held back from unleashing its full fury on British soil.

This hesitation was rooted in the German principle of Schwerpunktprinzip - the concentration of overwhelming force at the decisive point.

Diversion of effort was discouraged, and as such, the Luftwaffe refrained from full-scale operations against Britain until after the French armistice on 22 June.

Adolf Hitler and German Officers at the signing of the Armistice after the French surrender. On 22 June 1940, France signed an armistice with Germany in the same railway carriage at Compiègne where Germany had surrendered in 1918—a deliberate humiliation engineered by Hitler. The agreement divided France into an occupied zone under German control and a nominally independent Vichy regime. While fighting briefly continued overseas, the armistice marked the collapse of French resistance on the mainland and gave Germany free rein to focus on Britain as the next target of conquest.

...initiated more deliberate steps toward neutralising the island nation...

1940 Map showing the location of RAF Fighter Command groups and Luftlotte's 2 & 3 - now located in France and Belgium and within range of the UK.

https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/AAF/AAF-Luftwaffe/AAF-Luftwaffe-2.html

Still, German bomber crews began testing British defences even earlier.

Flying by night, they conducted limited sorties in May and June, more probing than punishing.

When Britain defied Hitler’s overtures for peace, the Luftwaffe initiated more deliberate steps toward neutralising the island nation.

Luftflotte 2 and Luftflotte 3 were redeployed to airfields in France and Belgium, putting them in striking range of southern England.

In June and July, German bombers carried out scattered night raids on coastal towns and inland targets—airfields, factories, and ports—designed to fray nerves and lower morale.

Their impact, however, was minimal and erratic, leaving British intelligence unclear about German intentions.

Luftwaffe air crews study maps in the summer of 1940. In the background is a Dornier Do 17 light bomber. Luftwaffe officers meticulously refined their plans for Kanalkampf, the battle of the Channel. Emphasising disruption of British coastal convoys, commanders such as Kesselring and Sperrle coordinated bomber, fighter, and E-boat operations to choke Britain’s supply lines. Reconnaissance units tracked shipping movements with increasing accuracy, while fighter groups prepared to lure the RAF into battle. These operations were seen not merely as harassment but as a calculated prelude to Adlerangriff, the decisive assault on Fighter Command.

Bundesarchiv, Bild 101I-341-0481-39A / Spieth / CC-BY-SA 3.0. https://battleofbritain1940.com/entry/wednesday-7-august-1940/

...the raids proved costly...

These night raids did, however, offer valuable experience.

German crews honed their use of navigational tools like the Knickebein system - radio beams that enabled aircraft to fix their position and locate targets with surprising accuracy.

On the night of 6/7 June, a Luftwaffe bomb fell on Addington in Greater London, a harbinger of what was to come.

But the raids proved costly; German bombers flying low were easily illuminated by searchlights and picked off by anti-aircraft fire.

By late June, they were forced to operate at higher altitudes, sacrificing accuracy to preserve aircraft.

Location and beam-pointing direction ranges of the initial Knickebein stations, September 1939. The Knickebein system was a German radio-beam navigation aid designed to guide bombers accurately to their targets, even at night or in poor weather. It projected intersecting radio beams over Britain, enabling crews to release bombs with greater precision. During the Battle of Britain, its introduction initially alarmed the RAF, but British countermeasures—led by scientists like R.V. Jones—quickly identified and disrupted the beams. Though innovative, Knickebein ultimately failed to provide the decisive advantage the Luftwaffe had hoped for.

https://www.nonstopsystems.com/radio/hellschreiber-modes-other-hell-RadNav-knickebein.htm

...had no desire to cooperate with the Kriegsmarine...

Commander of the Kriegsmarine Großadmiral Erich Raeder who clashed with Hermann Göring, commander of the Luftwaffe.

One area of strategic discord lay in Germany’s approach to maritime targets. Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, commander of the Luftwaffe, had little interest in naval warfare.

He viewed such operations as beneath his elite air force and had no desire to cooperate with the Kriegsmarine or its commander, Großadmiral Erich Raeder - whom Göring despised as a relic of the bourgeois class that Nazism had vowed to dismantle.

When the High Command of the Wehrmacht initiated what was essentially a naval blockade against Britain on 18 July, Göring refused to support it in any meaningful way.

He consistently sidelined Luftwaffe efforts to disrupt British shipping, insisting that air power should be reserved for military and strategic targets.

Not until February 1941 would this policy begin to shift.

A Kette (chain of three aircraft, or flight) of Ju 87B-1 is pictured over France in 1940. The Junkers Ju 87 Stuka dive-bomber, with its terrifying siren and precision attacks, was the defining symbol of the Luftwaffe’s fearsome air power in 1940. It represented the Blitzkrieg's synchronized speed and efficiency. However, this focus on land operations created internal friction. Reichsmarschall Göring, prioritizing his own air force’s prestige and Fighter Command’s goals over joint operations, was notoriously reluctant to allow the Luftwaffe to prioritize naval targets like convoys or Royal Navy ships. This refusal to fully commit air support to the Kriegsmarine was a major point of contention and limited the German Navy's effectiveness.

...control the skies, and Britain might be forced to the negotiating table...

Instead, Göring remained fixated on a decisive air battle.

In his directive of 30 June, he made it clear: the destruction of the RAF was the priority.

His belief was simple - control the skies, and Britain might be forced to the negotiating table.

At a high-level conference in Berlin on 31 July, Hitler presented the outline for Operation Sea Lion, the planned invasion of Britain.

Tellingly, no Luftwaffe representatives were present. Göring, absorbed in internal debates over which targets to prioritise, ignored repeated summonses to these inter-service meetings.

The German plans for Operation Sealion - the invasion of England. initial Army proposals of 25th July 1940 envisaging landings from Kent to Dorset, Isle of Wight and parts of Devon; subsequently refined to a confined group of four landing sites in East Sussex and western Kent.

...the unforgiving waters of the Channel...

Meanwhile, Luftwaffe commanders Hugo Sperrle and Albert Kesselring, tired of waiting for clear direction, began targeting British coastal shipping.

The logic was sound.

These targets were easier to locate than inland airfields or infrastructure, and striking at supply convoys could force the RAF into battle on terms that favoured the Germans.

Fighter Command would have to respond, and in doing so, expose its aircraft and pilots to combat over the unforgiving waters of the Channel.

Downed RAF pilots were far less likely to survive ditching at sea—Britain had no formal air-sea rescue service—while the Luftwaffe had developed one of its own.

The Luftwaffe was much better prepared for the task of air-sea rescue than the RAF, specifically tasking the Seenotdienst unit, equipped with about 30 Heinkel He 59 floatplanes, with picking up downed aircrew from the North Sea, English Channel and the Dover Straits. In addition, Luftwaffe aircraft were equipped with life rafts and the aircrew were provided with sachets of a chemical called fluorescein which, on reacting with water, created a large, easy-to-see, bright green patch. In accordance with the Geneva Convention, the He 59s were unarmed and painted white with civilian registration markings and red crosses. Nevertheless, RAF aircraft attacked these aircraft, as some were escorted by Bf 109s.

...place further strain on British logistics...

Moreover, closing the English Channel would sever a vital artery supplying the British war effort via the Thames Estuary.

Though convoys could be rerouted around Scotland, this would slow the flow of goods and place further strain on British logistics.

RAF chief Sir Hugh Dowding recognised the danger and requested that the navy divert shipping away from the most contested waters to reduce pressure on his fighter squadrons.

The Luftwaffe’s operations quickly developed a dual purpose: block British sea routes and lure Fighter Command into combat.

By July’s end, Luftflotte 2 and 3 had reached full strength—1,200 medium bombers, 280 dive-bombers, over 980 fighters, and nearly 140 reconnaissance aircraft, stretching from Hamburg to Brest.

Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding, Commander-in-Chief of RAF Fighter Command.

https://bentleypriorymuseum.org.uk/et-custom-timeline/acm-sir-hughd-dowding/

Dornier Do 17Z2 1.KG2 U5+GH foreground with crew having lunch at Epinoy France January 1940. After the fall of France in June 1940, Luftflotte 2 and Luftflotte 3 were positioned for the coming assault on Britain. Luftflotte 2, under Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, was based in northern France, Belgium, and the Netherlands, its strength comprising fighter units, notably the Messerschmitt Bf 109-equipped Jagdgeschwader, alongside medium bombers such as the He 111 and Ju 88. Luftflotte 3, commanded by Field Marshal Hugo Sperrle, operated from western and central France, with a heavy bomber concentration and long-range aircraft. Together they provided the main striking force against Britain, fully equipped, battle-hardened, and reorganised after the swift victory in France.

...limiting the number of fighters available to protect the south...

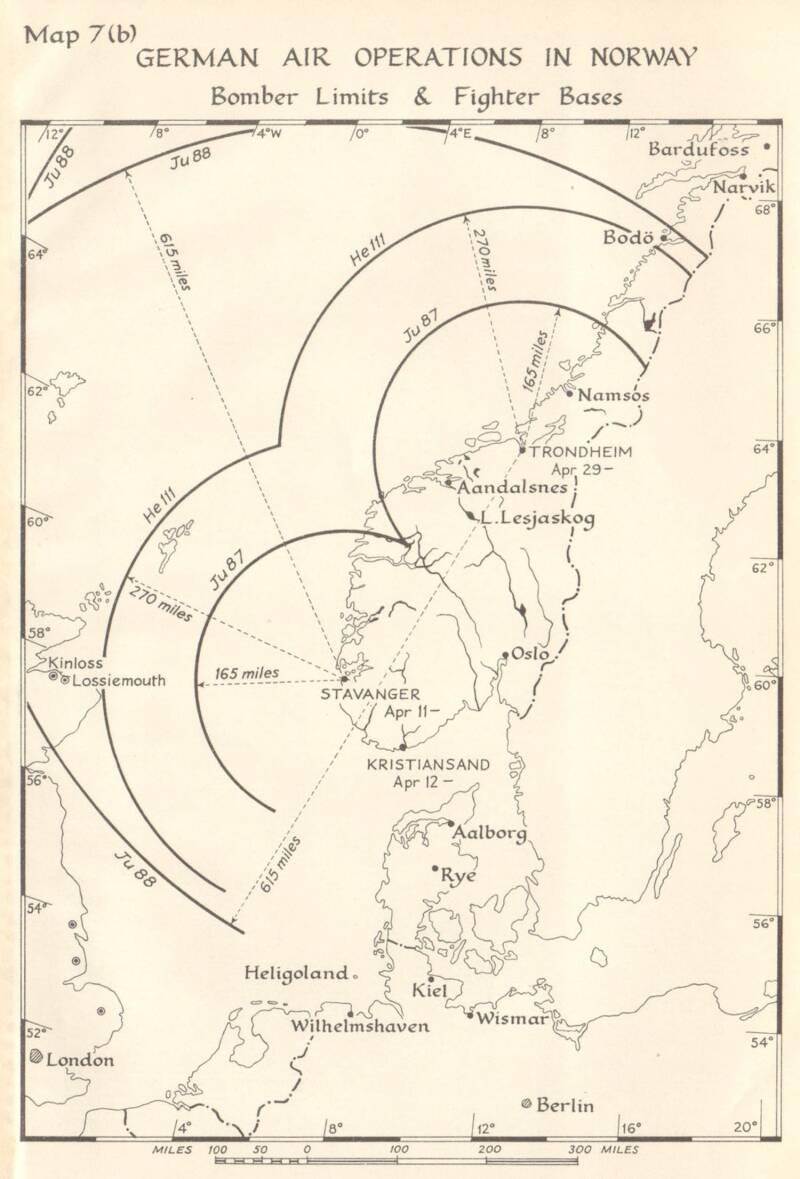

Meanwhile, Luftflotte 5 in Norway, though smaller, played a strategic role by compelling the RAF to retain a defensive presence in the north, limiting the number of fighters available to protect the south.

Thus began the Kanalkampf - the battle for the Channel - a prelude to the greater air war soon to rage across Britain’s skies.

It was a calculated move to test British resolve, probe defences, and draw blood. While the full-scale assault was still to come, the storm was already gathering.

Map showing German Air operation in Norway. In 1940, following the invasion of Norway, Luftflotte 5 (Air Fleet 5) established its headquarters in Oslo. Its primary mission during the Battle of Britain was conducting air operations against Northern Britain, specifically targets in Scotland, Northern Ireland, and North East England. Commanded by Generaloberst Stumpff, Lf 5 operated at a distinct disadvantage compared to the air fleets based in France. Due to the extreme range, its bombing raids were highly demanding and often lacked fighter escort. The long distances limited the effectiveness and frequency of its attacks across the North Sea.

Living In The Firing Line

The opening phase of Kanalkampf, brought the reality of war to the forefront for British civilians residing in coastal communities and those whose livelihoods depended on the crucial maritime and port infrastructure.

Unlike the rest of the country, which was still adapting to rationing and blackout rules, residents of the southeast coast were thrust onto the geographical frontline, demanding immediate and localized preparations.

Prior to the heavy engagement, coastal areas had already seen the implementation of defensive measures, including the erection of barbed wire, the emplacement of coastal artillery, and the posting of Home Guard units, giving the landscape a military edge.

Civilians were instrumental in contributing to these efforts, often voluntarily helping to dig trenches or fill sandbags around key town buildings.

This palpable sense of vulnerability spurred widespread, though not mandatory, self-evacuation; many families with the means to do so moved inland, recognizing that their proximity to the English Channel and German-occupied France made them inevitable targets.

Get your Air Raid Precautions approved curtain fabrics at Bradbeers on Above Bar Street. Hampshire Advertiser, 29th June 1940. For many living on or near to the South Coast, such precuations would become necessary. The shop was destroyed by enemy action in November 1940.

Administering first aid after a Luftwaffe bombing raid on Eastbourne. During the Kanalkampf in the summer of 1940, residents of Eastbourne lived under growing tension as Luftwaffe raids targeted Channel shipping and nearby coastal defences. Although not as heavily bombed as major ports, Eastbourne experienced air-raid alerts, occasional bombing, and the constant sound of aircraft battles offshore. Daily life was disrupted by blackouts, rationing, and the arrival of evacuees from larger cities. Many families sheltered nightly, while schools and businesses faced repeated closures. The psychological strain was as significant as the physical danger, as fear became a part of everyday life.

Sussex World Archive

...a continuous theater of operations...

The direct impact intensified dramatically once the Luftwaffe’s focus turned to systematically destroying the shipping convoys moving through the Straits of Dover and the nearby port facilities.

The skies over these areas became a continuous theater of operations, characterized by the roaring engagement of British and German aircraft.

Civilian air raid precautions (ARP) services, consisting of local volunteers, were constantly active, rushing to deal with the inevitable consequences of combat: the accidental jettisoning of bombs by damaged aircraft, and the debris and wreckage from shot-down planes falling onto residential areas.

The city of Brighton's location put it on the frontline during Kanalkampf. As a result, domestic and public buildings often took the full force of Hitler's bombs. Here, ARP personnel, aided by policemen and volunteers, rescue victims from the rubble.

https://player.bfi.org.uk/free/film/watch-brightons-blitz-1940-online

...severely damaged commercial and residential properties...

Towns like Dover and Portsmouth endured regular daylight attacks as the Germans attempted to knock out radar stations and naval facilities.

These raids not only caused direct casualties among residents, but they also severely damaged commercial and residential properties, frequently interrupting essential services like gas, water, and electricity, requiring prompt repair by civilian engineers under threat of further attack.

The wreckage of a Messerschmitt Bf 109 flown by 21 year old Lt. Josef Schauff from 8/JG 26 which crashed into Byron Avenue, Margate, Kent on 24th July 1940. The pilot bailed out moments before, but he died in the grounds of the Royal School for Deaf Children. During the Kanalkampf in summer 1940, Margate was directly affected because of its exposed position on the Kent coast overlooking the English Channel. Its location near vital shipping lanes made it vulnerable to air raids and artillery shelling as German forces attacked convoys and port towns. Residents endured frequent air-raid warnings, damage to property, and civilian casualties. Margate’s proximity to occupied Europe meant the war felt immediate, visible, and dangerously close.

Margate Local & Family History

...a prime military objective...

For those in maritime and port communities—dockers, stevedores, and merchant seamen—the threat was existential.

Their place of work was now designated a prime military objective. Merchant crews bravely continued to sail the Channel convoys, facing relentless aerial assault, resulting in substantial losses of both ships and lives.

This civilian sacrifice on the sea was a crucial preparation against defeat, ensuring that vital raw materials and food continued to reach the rest of the nation, albeit at a terrifying cost to the individuals involved.

The first phase of the Battle of Britain was in and along the Channel--the Kanalkampf. Much of this effort was in an around Dover. The Dover straits were the narrowest point of the Channel. It became known as the Hellfire Corner--the Channel area between Dover and Folkstone. This would continue throughout the Battle of Britain as many the RAF's forward fighter airfields were in Kent and many Luftwaffe flight plans crossed over the Dover/Folkstone area. And the same was true when the target shifted to London. Dover became a major target for the naval artillery guns set up as part of what would become the Atlantic Wall. The press caption here read, "Playing in Hell's Fire Corner: These children playing in the streets of this 'Front-Line' town of Dover, journaliticlly known as 'Hell's Corner,' not only are in constant danger from air bombings but live in constant peril of German long-range guns from across the Channel. The town is now the scene of an appeal by the Council for the Compulsory Evacuation of the local children. Owing to the difficulties, among others, of providing education under the general comditions."

World War II air campaign -- Battle of Britain phase 1 Kanalkampf

...creating economic hardship...

Liverpool Docks in the 1940's. Convoys diverted here during Kanalkampf would be safe from the attention of the Luftwaffe due to its position on the west coast of England. This would change though as the Battle of Britain evolved.

Port at War ~ Liverpool 1939-1945 ~ Mersey Docks and Harbour Board

On land, the disruption to port operations forced complex logistical changes, diverting ships to less vulnerable western ports and creating economic hardship for local businesses dependent on the Channel trade.

Despite the terror of living under an almost constant military threat, a local, tenacious resilience emerged, deeply rooted in the necessity of maintaining operational ports and holding the coastline against an anticipated, though ultimately unrealized, invasion.

The experience of the Kanalkampf thus served as a brutal preview for the coming months, conditioning the coastal populace to live and work under the direct shadow of enemy fire.

Hampshire Advertiser, 29 June 1940. Nightclubs offered a vital escape and psychological release from the daily threat and stress of the Blitz. Beneath the blackout, they provided a sense of defiant normalcy and community. People could forget the bombing, dance, and socialize, reinforcing the famous "Blitz spirit" of resilience and refusing to let enemy attacks halt everyday life. They acted as a morale booster and an essential social outlet.

The Internal Conflict

By 1940, the uneasy alliance between Britain’s military services remained brittle, strained by decades of rivalry.

Ever since the Royal Air Force was founded on 1 April 1918, it had fought not only its external enemies but also a turf war with the Admiralty and the War Office.

In the interwar years, the Army and Navy repeatedly tried to disband the RAF, eager to reclaim control of air power.

Though the bitterest infighting had eased by the Second World War—especially after the Fleet Air Arm returned to naval control—distrust lingered.

The Air Ministry, in particular, remained wary of the Army’s ambitions.

Sopwith 7F.1 Snipe E8015, Lieutenant Edward Mulcair of 'A' Flight, No. 43 Squadron RAF, ready for a patrol over the German lines. France, October 1918. The RAF, formed in April 1918, faced significant challenges during the interwar years. Rapid postwar demobilisation left it severely weakened, while budget cuts under the “Ten Year Rule” restricted expansion and modernization. Political debates questioned the RAF’s independence, with the Army and Navy seeking control of air power. Despite these obstacles, the service pioneered strategic bombing theories, developed new fighter designs, and established the world’s first integrated air defense system, laying crucial groundwork for 1939.

...mistrust flared into dysfunction...

That mistrust flared into dysfunction during the Battle of Dunkirk. RAF Fighter Command flew intense missions over the beaches to protect the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force, but losses mounted quickly.

By the 1st June 1940, the RAF had scaled back its cover to conserve its dwindling fighter strength.

In the air force’s absence, German attacks sank a minesweeper, a transport vessel, and three destroyers, with two more badly damaged.

The Royal Navy, bearing the brunt of those losses, grew increasingly frustrated with the RAF’s approach.

On the 15th August 1940 Pilot Officer Richard Hardy's Spitfire mk.1a was damaged in combat and he was forced to land near Cherbourg where it fell into German hands. This image shows the aircraft just after German markings were applied. During the Battle for France (May–June 1940), RAF fighter squadrons deployed in support of the British Expeditionary Force suffered heavy losses. Operating Hurricanes and a small number of Spitfires, they faced overwhelming numbers of experienced Luftwaffe pilots. In just six weeks, over 400 fighters were destroyed, many during desperate rearguard actions covering retreating Allied forces and the Dunkirk evacuation. Despite the losses, RAF pilots gained invaluable combat experience that proved critical during the forthcoming Battle of Britain.

https://www.reddit.com/r/wwiipics/comments/111ze8e/german_personnel_inspect_the_first_ever_raf/

...had overestimated kills...

Exaggerated claims didn’t help.

The RAF believed it had performed superbly, asserting it had shot down far more German aircraft than it had.

In reality, it had overestimated kills by a factor of four.

Of the 156 German aircraft lost during the campaign, only 102 could realistically be attributed to the RAF -- compared with 106 British aircraft lost.

Around 35 enemy planes had fallen to naval gunners. RAF leaders, however, remained convinced of their own effectiveness, while operational cooperation with the Navy remained minimal.

...fighting its own private war...

Rigid command structures hampered joint operations.

Fighter Command jealously guarded control over its units, and naval commanders complained that they couldn’t speak directly with RAF officers during combat.

This lack of coordination meant RAF fighters often arrived too late - or in too small numbers - to defend vulnerable ships.

The Admiralty’s frustration grew. It seemed to them that the RAF was fighting its own private war, detached from the wider struggle.

German soldiers inspect Sq/Ldr Geoffrey Dalton Stephenson’s Supermarine which was shot down over Dunkirk. The Dunkirk evacuation, Operation Dynamo, was characterized by significant tension between the Royal Navy (RN) and the Royal Air Force (RAF). Naval crews and soldiers, under continuous bombardment, felt the RAF was absent, leading to bitter accusations of inadequate air cover over the beaches. The RAF's operational priority, however, was to intercept and destroy Luftwaffe bombers and high-flying fighters before they reached the area, often fighting high above visible range. Fighter squadrons were also restricted by the limit of their range from English airfields, allowing only brief patrols. Furthermore, RAF Command was determined to preserve its Hurricanes and Spitfires for the anticipated Battle of Britain. Though the RAF lost 145 aircraft, the perceived lack of close support created lasting resentment among the rescued troops and sailors.

...hardly the basis for strong wartime collaboration...

Vice Admiral Max Horton, in charge of operations at Dover during the Dunkirk evacuation, attempted to bridge the gap.

He requested a face-to-face meeting with Air Chief Marshal Hugh Dowding to iron out the issues.

Instead, Horton was told to write a formal complaint - hardly the basis for strong wartime collaboration.

The meeting never happened.

The Daily Sketch newspaper reports on the success of Operation Dynamo - the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) from Dunkirk. The success of the operation, belied the tensions between the RAF and the Royal Navy. The Royal Navy desperately demanded continuous air cover during Operation Dynamo to protect evacuation ships from the relentless Luftwaffe dive-bombers. However, the RAF, prioritizing the conservation of Fighter Command for the coming Battle of Britain, often restricted its fighters to high-altitude patrols over land. This strategic choice caused severe tension, leading the Navy to complain bitterly of inadequate support, unaware that the decisive air battles were often taking place miles inland, safeguarding the RAF's long-term strength.

...quickly strained its resources...

Air Vice-Marshal Keith Park, commander of RAF 11 Group, Fighter Command.

The question of protecting shipping was especially controversial.

Each day, around a dozen convoys passed through the Channel, and about a third were attacked. RAF 11 Group, under Air Vice-Marshal Keith Park, bore the responsibility of defending southeastern England, and convoy protection quickly strained its resources. Ironically, the strategy of hugging the coastline for safety backfired.

Operating close to the continent gave German bombers the tactical advantage. Radar along the coast provided minimal warning, and the Luftwaffe, operating from nearby bases in France, could strike swiftly and withdraw before fighters could intercept.

Permanent fighter patrols over convoys were one solution, but they exhausted pilots and left the RAF reacting rather than acting. The Germans dictated the tempo.

In the early phases of the Battle of Britain, the coastal Chain Home radar system, while revolutionary, often struggled with accurate low-altitude detection. This critical limitation meant the warning period was frequently minimal, particularly for raids skimming the water. The Luftwaffe's strategic advantage lay in its close proximity to the English coast, launching missions from bases in occupied France. Consequently, German strike forces could execute quick, devastating attacks and rapidly withdraw across the Channel before RAF Fighter Command could consistently achieve timely, effective aerial interception.

Imperial War Museum

...urging the Navy to use convoys as bait...

Although the Air Staff officially supported convoy defence, Dowding believed that Fighter Command’s resources had to be preserved for the decisive air battles he saw on the horizon.

He anticipated that the Luftwaffe would launch widespread attacks—not just on convoys but on airfields, ports, and factories—to bait RAF fighters into costly combat.

On 3rd July, Dowding requested that merchant convoys be rerouted north around Scotland, alleviating pressure on his squadrons.

The Air Ministry agreed—until, bowing to naval pressure, it reversed course four weeks later.

On the 9th August, Prime Minister Churchill was still urging the Navy to use convoys as bait to lure German bombers into action.

The tactic worked, but it came at a heavy cost in aircraft and experienced pilots.

Convoy routes around the UK. From 3rd July, Dowding requested they be rerouted around Scotland.

https://www.naval-history.net/MapB1940-AtlanticConvoyRoutes.htm

Captain and his crew keep watch from the bridge of a ship in an Atlantic convoy. Although the Air Staff publicly endorsed the defence of merchant convoys, Dowding increasingly doubted that Fighter Command could afford to divert scarce fighters and experienced pilots to patrols over open water. He was convinced that such duties would drain strength without yielding decisive results, and that Britain’s limited air power had to be husbanded for the far greater struggle he believed was imminent. In Dowding’s view, preserving his command intact for the coming battle over Britain itself outweighed the short-term demands of maritime protection.

...the invasion threat felt real...

Beyond Britain’s shores, RAF reconnaissance aircraft like Spitfires and Lockheed Hudsons flew high-risk sorties, photographing ports from Norway to Spain in search of signs of an imminent invasion.

They found nothing—until mid-August, when photos showed barges amassing at northern French ports.

Suddenly, the invasion threat felt real.

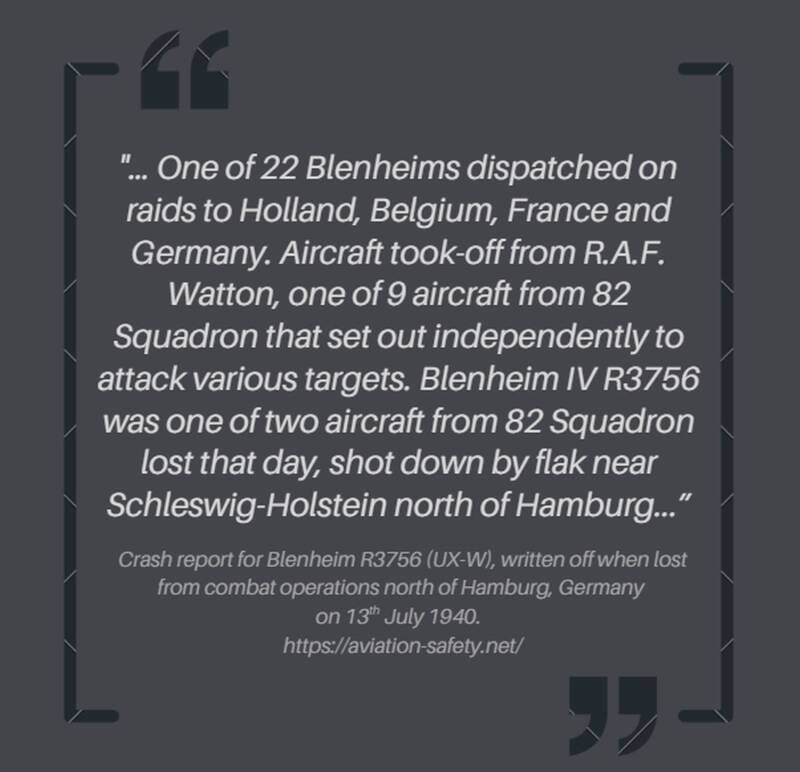

Bomber Command was already engaged in nightly raids against German-held ports, factories, and airfields. Its Blenheim bombers, flying mostly in daylight, hit Luftwaffe bases when weather permitted.

A Lockheed Hudson of No. 220 Squadron RAF approaches Dunkirk on a reconnaissance patrol during the evacuation of the BED from the French port in May-June 1940. During the build up to the Battle of Britain, the Photographic Reconnaissance Unit (PRU) pilots, flying unarmed Spitfires and Lockheed Hudsons, played an absolutely vital, albeit high-risk, role in intelligence gathering. They flew daring, solitary sorties, sometimes covering thousands of miles across contested skies. Their primary mission was the continuous, meticulous photography of enemy-held ports and coastal regions stretching from Norway down to Spain, desperately searching for any concrete evidence or telltale movements indicating an imminent German invasion fleet.

...made strafing runs suicidal...

By July, port infrastructure and shipping had become priority targets.

But with German airfields numbering in the hundreds - and their aircraft dispersed and well-defended - bombing results were poor.

Heavy flak made strafing runs suicidal, and the vulnerable Blenheims, often grounded by bad weather, required near-complete cloud cover to proceed.

By late June, 90 percent of sorties were aborted. When the moon rose, a few Fairey Battles and Blenheims flew night missions, but losses were severe - 72 bombers were lost in July alone.

Fairey Battles in flight. Despite its vulnerabilities already being exposed during the Battle of France, it continued to be deployed in operations against German shipping massed in the Channel ports for Operation Sealion.

#Messerschmitt Fodder - U.K. Fairey Battle with Tons of Photos

...technology lagged behind ambition...

Swansea as dawn breaks after the three night blitz attack by the Germans. The night Blitz exposed RAF weaknesses in 1940–41. Effective by day, Fighter Command lacked proper night-fighting tools: early radar was unreliable, ground control struggled to track raiders, and pilots depended on searchlights. Interceptions were scarce, letting the Luftwaffe strike cities freely and forcing rapid improvements in radar, aircraft, and tactics.

The 75th anniversary of Swansea's three-night blitz commemorated in stage show | Wales Online

Fighter Command, for its part, struggled with night combat.

In June, it claimed 21 bombers shot down in darkness, but only seven could be confirmed.

Night air defence remained primitive.

There were no purpose-built night fighters, no effective radar for tracking aircraft after they crossed the coast.

As the Blitz intensified in October, the Luftwaffe flew 5,900 night sorties, losing just 23 planes - a mere 0.4% loss rate.

These failures ultimately cost Dowding his position in November 1940.

Despite their courage, Britain’s airmen were still feeling their way through a rapidly evolving war.

Coordination was flawed, technology lagged behind ambition, and institutional rivalries undermined unity of effort.

But in the crucible of the Battle of Britain, every costly lesson shaped the defences that would, in the end, hold.

Concertina wire defences along the sea front at Sandgate, near Folkestone in Kent, 10 July 1940. In July 1940, following heavy equipment losses at Dunkirk, Britain mobilized for immediate defense against the looming German invasion, Operation Sea Lion. Defenses were improvised and focused on depth. Immediate beach defenses consisted of anti-tank obstacles, mines, wire, and thousands of newly built pillboxes. These were largely crewed by the hastily-formed, often poorly-armed Home Guard and exhausted regular troops. Inland, stop lines—like the GHQ Line—used concrete fortifications and natural barriers to contain any armored breakthrough. With coastal artillery severely lacking, the most critical element was the RAF’s Fighter Command, tasked with destroying German invasion barges before they could reach the vulnerable shore.

IWM (H 2187) Wednesday 10 July 1940 | The Battle of Britain Historical Timeline

Breaking the Codes

After the fall of France in June 1940, the volume of Luftwaffe Enigma signals intercepted by British codebreakers dropped sharply.

With secure landlines now running through occupied territory, the Germans relied less on radio.

But by the end of June, enough messages trickled through to reveal a clear and ominous picture: the Luftwaffe was regrouping in Belgium and Holland, preparing for a major offensive against Britain.

Photographic reconnaissance flights confirmed the construction of longer runways across enemy-occupied airfields.

Though no invasion fleet had yet been spotted in the Channel ports, these signs suggested that preliminary air operations were imminent.

Adolf Hitler and his officers after the fall of France. The Eiffel Tower can be seen in the background. After the fall of France, Bletchley Park’s codebreakers faced immense challenges. The Germans altered Enigma procedures, introducing more complex key settings and stricter communication discipline, slowing decryption efforts. Crucial listening posts in France and Norway were lost, reducing intercept coverage. Rapid Luftwaffe redeployments across the Channel created new signal volumes to process, straining resources. Despite these obstacles, breakthroughs in cribbing, the development of early bombes, and collaboration with intercept stations enabled codebreakers to gradually recover their edge during Kanalkampf.

https://www.deviantart.com/julia-koterias/art/Adolf-Hitler-in-colour-14-518549548

...launched a wave of daylight attacks...

On 10 July, after weeks of minor night raids, the Luftwaffe launched a wave of daylight attacks targeting British ports, coastal convoys, and aircraft factories—marking the opening phase of the Battle of Britain.

Thanks to earlier Enigma decrypts and intelligence work, Britain’s Air Intelligence branch (AI) had already predicted this shift.

For months, codebreakers at Bletchley Park had been piecing together the Luftwaffe’s structure, order of battle, and equipment by analysing tactical signals sent in less-secure radio codes.

These breakthroughs allowed British intelligence to revise key assumptions, reducing their estimate of Germany’s bomber strength from 2,500 to around 1,250 by 6th July - much closer to the actual figure of 1,500–1,700.

Codebreakers at Bletchley Park. In the months before Kanalkampf, Bletchley Park’s work on breaking Luftwaffe Enigma traffic advanced steadily, giving the RAF partial but valuable insight into German planning. Although decrypts were not yet consistent, analysts were able to piece together information on Luftwaffe orders of battle, airfield locations, and operational patterns. By July 1940 this groundwork meant that, during Kanalkampf, Britain possessed an emerging edge: intelligence that helped predict convoy attacks, improving RAF readiness and contributing to the survival of vital Channel shipping routes.

https://www.bletchleypark.org.uk/our-story/who-were-the-codebreakers/

...they recognised that a major effort was looming....

While the Luftwaffe preferred to communicate strategic changes by landline, hints of shifting plans still surfaced in encrypted messages.

One such discovery was the code name Adlertag - “Eagle Day”—and its association with operations scheduled between 9 and 13 August.

Though the British didn’t yet understand its exact meaning, they recognised that a major effort was looming.

As the Luftwaffe's attacks intensified in the Kanalkampf - the "Channel Battle" - Enigma decrypts began to offer more tactical insights: raid sizes, timings, and sometimes even targets.

But this information often arrived too late to be actionable.

Rapid Luftwaffe changes rendered some of the intelligence obsolete before it reached RAF commanders.

Coordination between Enigma intercepts and other intelligence sources, particularly RAF Y-stations, was also inconsistent.

Dornier Do 17Zs 7.KG3 flying in formation Battle of Britain. The Dornier Do 17, nicknamed the “Flying Pencil,” played a major role in Kanalkampf, conducting low-level raids on shipping. Fast but lightly armed, it proved increasingly vulnerable to Hurricanes and Spitfires.

Wick RAF Y Station. During Kanalkampf, coordination between Enigma decrypts and other intelligence sources, particularly RAF Y-stations, was uneven and sometimes fragmented. Y-stations provided raw intercepts of Luftwaffe wireless traffic, but delays in analysis and transmission meant insights often reached commanders too late for immediate operational use. Furthermore, Enigma decrypts, while increasingly valuable, could not always be reconciled quickly with Y-station reports. This lack of seamless integration limited Fighter Command’s ability to form a complete, timely intelligence picture during the Channel battles.

...intercepting German wireless transmissions...

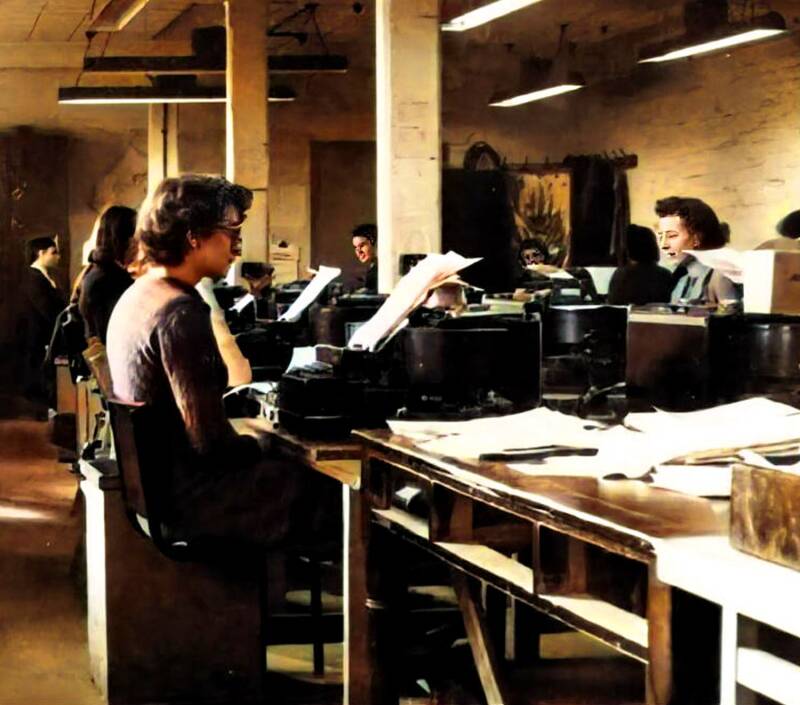

RAF Y-stations operated independently from Bletchley Park, intercepting German wireless transmissions between aircraft and their ground controllers.

These stations sometimes picked up Luftwaffe sightings of British convoys or overheard plans for imminent strikes.

By August, this real-time voice traffic began to complement radar and Enigma data more effectively.

The key to this eavesdropping effort was a dedicated team of German-speaking women from the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) and the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS).

Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS) operators at Beaumanor Army Y Station. The ATS, along the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) and the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS) played vital roles in the Enigma intelligence effort. WAAF personnel operated radar, tracked German aircraft, and maintained communications that supported interception work, while WRNS members—known as “Wrens”—worked at Bletchley Park running bombe machines, processing decrypts, and managing vital clerical and analytical tasks. Their precision, discipline, and secrecy enabled intelligence from Enigma to be turned into timely operational advantage for British forces.

...a cat-and-mouse game in the air...

Operating from RAF Kingsdown in Kent and other listening posts, they monitored Luftwaffe radio telephone conversations and fed intelligence into the heart of the Dowding system—Fighter Command’s integrated air defence network.

Voice transmissions occasionally revealed crucial details beyond radar’s reach: the height of incoming formations, distinctions between bombers and fighter escorts, orders for diversionary attacks, and even real-time Luftwaffe reactions to RAF countermeasures.

It was a cat-and-mouse game in the air, and every intercepted word brought Britain a little closer to staying one step ahead.

CORONA operating position at the Headquarters of the RAF 'Y' Service, Hollywood Manor, West Kingsdown, Kent. A German-speaking operator is speaking into the 'ghost voice' microphone (top), while a WAAF flight-sergeant records the exchanges on a German receiver. The gramophone turntable was used for jumbled-voice jamming on Luftwaffe radio frequencies. CORONA was a highly secret British wartime intelligence system within the Y Service that captured and analysed German VHF voice transmissions during the Second World War. Unlike Morse-coded traffic sent by Enigma, CORONA operators listened live to Luftwaffe radio chatter between pilots and ground controllers. By transcribing these conversations in real time, they provided rapid, tactical intelligence on German air operations, allowing RAF Fighter Command to respond more quickly, posicioning interceptors and strengthening Britain’s air defence system.

Imperial War Museum

Convoys Under Fire: Coal, Codes, and Chaos at Sea

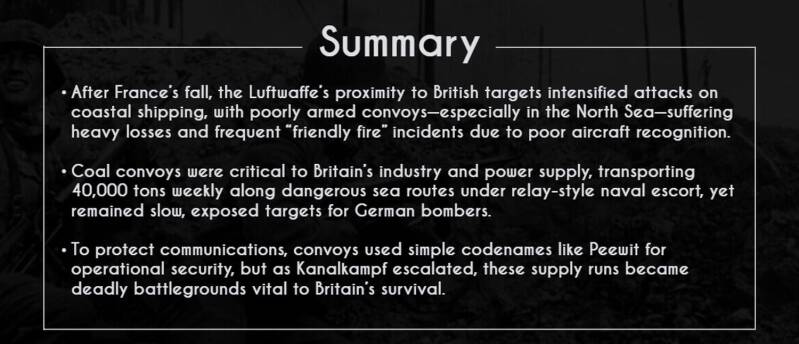

With the fall of France and the Low Countries in spring 1940, the Luftwaffe gained immediate access to airfields along the English Channel, drastically shortening the range to their targets.

The result was a swift and deadly escalation in German attacks on British coastal shipping.

In the North Sea, the Grimsby fishing fleet had already felt the sting of air assault, suffering two attacks in June alone.

By July, air raids had become so frequent that shipping losses off the east coast exceeded those caused by naval mines.

The Kingston Pearl, a Grimsby-owned vessel, which was requisitioned as an anti-submarine trawler during the Second World War. During the Kanalkampf in 1940, the Luftwaffe launched frequent air raids along the East Coast, targeting shipping and ports. Grimsby, a key fishing hub, faced severe disruption as German bombers and dive-bombers attacked vessels and dockside facilities. Many trawlers were sunk or damaged, leading to significant loss of crews and equipment. Fishing operations were curtailed, with ports often closed during raids, and insurance and repair costs soared. The attacks strained local communities reliant on the fleet, causing economic hardship and fear among fishermen. Despite losses, some vessels continued operations under naval escort, maintaining limited supplies to Britain.

...could disrupt bombing runs...

Merchant ships, minesweepers, and patrol vessels found themselves increasingly vulnerable.

The Royal Navy’s limited supply of light anti-aircraft weaponry left convoys exposed, particularly as the bulk of Britain’s air defence resources had been redirected to the southeast in anticipation of a possible invasion.

Despite the shortage, the Admiralty maintained that ships should fire upon any aircraft taking an apparent attack course - an aggressive tactic that, when executed with precision and volume, could disrupt bombing runs and even down enemy aircraft.

Royal Navy anti-aircraft gunners man a 20mm Oerlikon autocannon whilst helping guard a convoy enroute to Malta, 1940. During the early stages of the war, the Royal Navy faced a serious shortage of light anti-aircraft weapons as the rapid expansion of the fleet outpaced production. Many ships lacked sufficient close-range defences, relying instead on machine guns that were often ineffective against fast, low-level aircraft. The limited availability of weapons such as the 20mm Oerlikon left vessels vulnerable to air attack, contributing to heavy losses during convoy operations and early wartime naval engagements.

...better recognition training and improved communication were essential...

However, this approach had unintended consequences.

Poor training and limited experience in aircraft recognition among naval crews led to numerous cases of "friendly fire" against RAF planes - even those providing direct escort.

The RAF strongly objected to the Admiralty's rule requiring ships to fire at unidentified aircraft within 1,500 yards.

As more pilots were mistakenly attacked, it became clear that better recognition training and improved communication were essential.

Over time, both airmen and seamen adapted, reducing incidents through better coordination and discipline.

An aircraft identification book produced in Britain in 1940. Poor training and limited experience in aircraft recognition among naval crews in 1940 significantly increased the risk of “friendly fire” incidents involving RAF aircraft. Under intense pressure from frequent air attacks and with inadequate time for preparation, sailors often struggled to distinguish between friendly and enemy planes. The Luftwaffe’s use of similar flight profiles and low-level attack tactics further complicated identification, leading to tragic mistakes. These incidents highlighted shortcomings in early-war coordination between the Royal Navy and the RAF, prompting improved training, better communication procedures, and the wider use of recognition signals to reduce such occurrences.

BRITISH & GERMAN AIRCRAFT RECOGNITION 1940 WW2 IDENTIFICATION OTHERS ON | #1779147467

...industry, railways, shipyards, and power stations relied heavily on coal...

Among the most vital shipping operations were the coal convoys.

British industry, railways, shipyards, and power stations relied heavily on coal from Wales, Northumberland, and Yorkshire.

These massive shipments moved by sea to London Docks and other key ports, with routes threading dangerously through the North Sea and the Channel - waters now patrolled by the Luftwaffe.

Coal convoys followed designated routes. Those sailing east from Wales and Glasgow were known as CE (Coal East) convoys, while those returning were designated CW (Coal West).

...lumbering, and highly exposed...

Their passage was painstakingly choreographed: destroyers and armed trawlers from multiple Royal Navy commands handed off escort duty like runners in a relay race—from Falmouth to Portland, to Portsmouth, to Dover, and finally to the Thames Estuary.

Slow, lumbering, and highly exposed, these ships were sitting ducks for German bombers.

Yet the need was urgent: the south coast required 40,000 tons of coal per week, and the rail network simply couldn’t handle the load.

...a clumsy mouthful ripe for garbled transmission...

To maintain operational security and ease of communication, convoys were given code-names.

Rather than broadcasting a designation like “CW 9” over radio - a clumsy mouthful ripe for garbled transmission - naval command assigned simple, reusable words such as Peewit, Booty, Bacon, or Fruit.

These codenames were reserved for use by convoy escorts and senior officers only; merchant crews were forbidden from broadcasting them.

For example, CW 9 (Peewit) was the codename for a July convoy that would soon find itself under ferocious German attack.

...battlegrounds in a war of attrition...

The convoys that crept along Britain’s shores during this time were more than logistical efforts—they were battlegrounds in a war of attrition.

Each coal ship that made it to port helped keep factories humming, lights burning, and trains running.

But each one risked becoming a blazing wreck under German bombs.

As Kanalkampf intensified, Britain’s struggle to defend its lifelines at sea became just as vital—and just as costly—as the air war above.

10th July

On 30 June 1940, Göring ordered the Luftwaffe’s II. and VIII. Fliegerkorps—rich in Stuka dive-bombers—to take the fight to Britain’s coastal lifelines.

Oberst Johannes Fink, the new Kanalkampfführer, coordinated strikes on Channel convoys, pairing Bf 110 “destroyers” as close escort with Bf 109s free to hunt RAF fighters.

The aim was twofold: sink merchantmen carrying coal, food, and raw materials—and lure Fighter Command into battle.

The 10th July dawned grey and wet, but the Luftwaffe pressed on. At 05:15, the first bombs fell on RAF aerodromes in East Anglia, causing minor damage but destroying several parked aircraft.

At 08:15, a Do 17 was intercepted off Yarmouth; its pilot and observer killed before it crashed into the sea—the RAF’s first confirmed kill of the Battle of Britain.

Reports on the Luftwaffe attacks on the opening day of Kanalkampf - 10th July 1940, as reported the following day in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 11th July, 1940. The opening day of Kanalkampf was widely reported across the world’s press as a dramatic escalation in the air war. British newspapers stressed the heroism of RAF pilots defending convoys, while German outlets hailed Luftwaffe successes. Neutral nations, such as Switzerland and Sweden, noted the scale of the clashes with cautious analysis, while American papers described the fighting as a potential prelude to invasion. Across headlines, Kanalkampf was portrayed as the opening act of a decisive struggle.

...clashing in a swirling dogfight...

Convoy CW 3, codename Bread, became the day’s main target.

Spotted mid-morning, it was attacked at 13:50 by 26 Dorniers, 30 Bf 110s, and 20 Bf 109s.

RAF Hurricanes and Spitfires scrambled from multiple squadrons, clashing in a swirling dogfight over the Channel.

Flying Officer Peter Higgs of No. 111 Squadron was killed when his Hurricane collided with a bomber.

German claims of sinking a cruiser and four merchant ships proved wildly exaggerated—only a single sloop was lost—while German losses reached at least 14 aircraft.

...beginning the war of attrition...

Later, sixty Ju 88s from Luftflotte 3 bombed Swansea and Falmouth, wrecking an ammunition factory, damaging port facilities, and sinking several ships, including the tanker Tascalusa.

By nightfall, both sides had suffered losses, but Britain’s convoys continued to sail.

For the Luftwaffe, the day was a probing strike—testing RAF response times, assessing convoy defences, and beginning the war of attrition Göring hoped would clear the skies for invasion.

For the RAF, it was the first real day of the battle for Britain’s survival.

A flight of RAF Hawker Hurricanes. During Kanalkampf, the Hurricane proved indispensable to the RAF’s defence of Channel convoys. Robust and reliable, it bore the brunt of the fighting against German bombers, its eight .303 Browning guns inflicting heavy losses. While less agile than the Messerschmitt Bf 109 in dogfights, the Hurricane’s stability and firepower made it highly effective in convoy patrols. Its resilience under fire and ease of repair ensured it remained the backbone of Fighter Command during this opening phase.

11th July

On 11th July 1940, the English Channel became a fierce battleground as the Kanalkampf escalated into a series of intense aerial and naval clashes.

At dawn, scattered Luftwaffe raids tested British defenses from Yarmouth to Flamborough Head.

Bombs fell on the Royal Engineer Headquarters in Derbyshire and an ammunition truck near Bridlington, causing extensive damage but no confirmed casualties.

Messerschmitt Bf 110C-4 (W.Nr: 3551 2N+EP) of 9./Zerstörergeschwader 76 lies in a field at Grange Heath, near Lulworth in Dorset, following combat over Portland at 12:10 on 11 July 1940. Surprised at 12,000 ft by Green Section of No. 238 Squadron, the aircraft force-landed after being harried by S/L John S “Johnny” Dewar of No. 87 Squadron and F/O Hugh J Riddle of No. 601 Squadron. The pilot Oberleutnant Gerhard Kadow and his gunner Gefreiter Helmut Scholz were both captured. Kadow was shot in the foot while attempting to set fire to the aircraft.

Thursday 11 July 1940 | The Battle of Britain Historical Timeline

...disrupted the attack...

By 07:00, RAF Spitfires and Hurricanes scrambled to intercept German bombers.

No. 66 Squadron damaged a Dornier Do 17 near Walton-on-the-Naze, while Douglas Bader’s No. 242 Squadron shot down another off Cromer, losing one Hurricane pilot rescued after bailing out.

The main morning strike saw Ju 87 Stukas of StG 2, escorted by Bf 109s, target a British convoy in Lyme Bay.

Despite valiant efforts by No. 501 and 609 Squadrons, the Stukas sank HMS Warrior II, killing one crewman.

RAF fighters disrupted the attack but suffered losses, including Sgt. Dixon.

RAF personnel examine the wreck of Heinkel He 111H (G1+LK) of 2./KG 55 on East Beach, Selsey in Sussex, shot down by P/O Wakeham and P/O Lord Shuttleworth of No. 145 Squadron on 11th July 1940 during a sortie to attack Portsmouth dockyards. Oblt. Schweinhagen, Ofw. Slotosch and Fw. Steiner were all captured wounded. Uffz. Mueller died on his way to hospital and Ofw. Schlueter died of his wounds the same day.

https://battleofbritain1940.com/entry/thursday-11-july-1940/ © IWM (HU 72441)

...the Luftwaffe paid a heavy price...

At 11:10, a major raid on Portland Harbour involved Ju 87s escorted by about 40 Bf 110s.

RAF Hurricanes and Spitfires engaged fiercely, shooting down several German aircraft, including four Bf 110s and killing Oberleutnant Hans-Joachim Göring.

Although Portland’s harbour was damaged, the Luftwaffe paid a heavy price, exposing the vulnerability of the Bf 110 escort fighters.

Article in the New York Times, 12th July 1940, reporting on the Luftwaffe attacks the day before during Kanalkampf. American newspapers such as The New York Times reported on Kanalkampf with a mixture of distance and fascination. Coverage highlighted the escalating clashes over the English Channel, portraying them as a prelude to a larger German offensive. Reports often emphasised the bravery of RAF pilots and the peril faced by Channel convoys, while cautiously analysing German intent. Though restrained in tone, the U.S. media conveyed a sense that the battle marked a critical turning point for Britain’s survival.

...serious damage to the city’s gasworks...

Later, a Heinkel He 111 raid on Portsmouth was met by Hurricanes from Nos. 601 and 145 Squadrons, resulting in significant German bomber losses and serious damage to the city’s gasworks.

Pilots reported German attempts to jam British radar using metallic debris.

Night raids continued with bombings on Bristol and other targets, but RAF night fighters, hindered by clouds, made no interceptions.

The day highlighted growing Luftwaffe confidence but also revealed weaknesses exploited by the RAF.

The Battle of Britain edged closer to a decisive confrontation.

The nose gunner in the HE-111 German medium bomber. On 11th July 1940, Heinkel He 111 bombers of the Luftwaffe spearheaded attacks against British shipping in the Channel. Operating in tight formations, they targeted convoys with a mix of bombs and defensive fire, testing RAF Fighter Command’s ability to respond. Escorting Bf 109s sought to fend off Hurricanes and Spitfires, but several Heinkels were lost in the fierce combats. The day revealed both the resilience of British defences and the He 111’s vulnerability without strong fighter cover.

12th July

On the 12th July 1940, the Kanalkampf raged relentlessly from the Thames Estuary to the Scottish coast amid grey skies and heavy rain.

British convoys Booty and Agent steamed along vital coastal routes, targeted by persistent Luftwaffe reconnaissance and bombing raids, especially near Portland and the East Anglian coast.

Early engagements saw Flying Officer J.H.L. Allen shot down near Orford Ness, emphasizing the deadly risks of routine patrols.

...a swift RAF response...

By mid-morning, powerful Luftwaffe formations of Heinkel He 111s and Dornier Do 17s attacked the convoys, prompting a swift RAF response from multiple squadrons including Douglas Bader’s No. 242 Squadron.

Fierce dogfights resulted in several German bombers being downed, including the loss of Staffelkapitän Hauptmann Machetzki, while the convoys suffered minimal damage - only the SS Hornchurch was sunk.

Farther north, the Luftwaffe bombed Aberdeen’s shipyards and city, killing dozens of civilians and damaging infrastructure.

Civilians and RAF airmen inspect the burning remains of a Heinkel He 111 which was shot down by Spitfires of No. 603 Squadron over Aberdeen, Scotland and crashed into the newly-built Ice Rink on Anderson Drive.

IWM (HU 71114) https://battleofbritain1940.com/entry/friday-12-july-1940/

...killing dozens of civilians and damaging infrastructure...

Spitfires intercepted and downed enemy bombers, including one crashing into a local ice rink, adding to the devastation.

Afternoon raids continued along the south coast and the Solent, with German bombers striking naval and coastal targets but suffering losses, such as a He 111 crashing into a pub near Portsmouth.

Multiple skirmishes across Cornwall, Devon, and Norfolk involved Hurricanes and Spitfires, with successful interceptions like the shooting down of a He 111 off Essex by No. 74 Squadron.

Nightfall brought further Luftwaffe raids on South Wales, Somerset, and Scotland, continuing the unyielding pressure on British defenses.

The 12th of July marked a brutal day of attrition and resilience, highlighting the expanding scope of the Luftwaffe’s campaign and the fierce RAF defense that would shape the Battle of Britain’s outcome.

Heinkel 111P G1+FA of Stab./Kampgesschwader 55. Coming in over the Isle of Wight and Southampton Water it was attacked by six Hurricanes of Nº 43 squadron and promptly dropped the bomb load of sixteen 50 kg and crash landed near the 'Horse and Jockey Inn', Hipley, NW of Portsmouth, Hampshire, on the 12th July 1940. The aircraft pictured shortly after landing and disguised from the air, to prevent the Luftwaffe sighting it and damaging it beyond repair. The five crew were taken prisoner but the observer died of his wounds in hospital.

https://www.facebook.com/colourbyRJM

July 13th

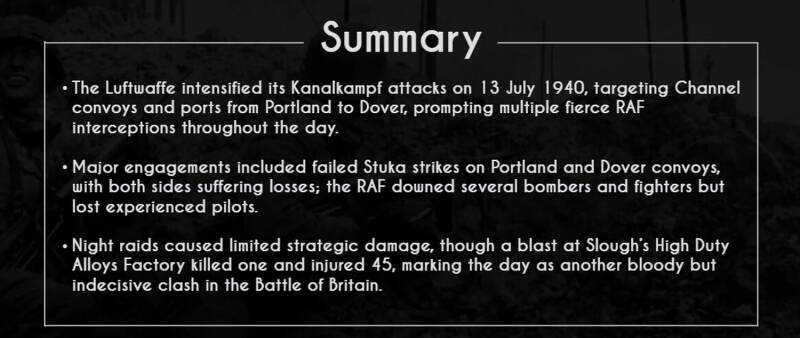

Saturday, 13 July 1940 began under a shroud of fog along England’s southern coast.

As the haze lifted, the Luftwaffe pressed its Kanalkampf offensive, striking at Channel convoys and coastal points from Portland to Dover.

Fighter Command rose to meet them, sparking fierce clashes in the air. Morning skirmishes saw Hurricanes from No. 501 Squadron down a Dornier Do 17 west of Southampton, while No. 43 Squadron destroyed a Heinkel He 111 over Spithead.

These early duels foreshadowed the day’s escalating violence.

...were pounced on by Hurricanes and Spitfires...

At 14:20, forty German aircraft—Ju 87 Stukas with Bf 110 escorts—targeted a convoy off Portland.

Missing their prey, they formed defensive circles and were pounced on by Hurricanes and Spitfires.

One Bf 110 fell, two Stukas failed to return, but the RAF lost Flt. Lt. J.C. Kennedy in combat.

By 17:30, Stukas and Bf 109s struck Dover Harbour and a nearby convoy.

AA guns and No. 64 Squadron Spitfires drove them off, claiming several probable kills.

Junkers Ju 87 Stuka dive bombers during Kanalkampf. In early July 1940, the Ju 87 Stuka dive-bomber became a feared weapon against British convoys in the Channel. Its terrifying siren, precision bombing, and steep diving attacks proved highly effective against shipping. Yet, despite initial successes, the Stuka’s vulnerability soon became apparent. Lacking speed and defensive armament, it suffered heavy losses when confronted by RAF fighters. These early encounters foreshadowed the Stuka’s diminishing role as the Battle of Britain intensified.

https://battleofbritain1940.com/entry/saturday-13-july-1940/

...minor raids harried convoys off Harwich and North Foreland...

The day’s fiercest combat erupted off Calais at 18:00, when No. 56 Squadron’s Hurricanes and No. 54 Squadron’s Spitfires tangled with Ju 87s and JG 51 fighters attacking Convoy CW 5.

RAF pilots claimed multiple kills, including Leutnant Hans-Joachim Lange of JG 51, but suffered losses.

HMS Vanessa was disabled by near-misses.

Elsewhere, minor raids harried convoys off Harwich and North Foreland.

Scattered bombs fell in Dorset and Dundee without major effect.

Nightfall brought reduced Luftwaffe activity, mostly suspected minelaying. At 23:10, a massive explosion ripped through the High Duty Alloys Factory at Slough, killing one and injuring 45.

Bombs also fell on railway lines in Co. Durham, damaging property and killing livestock. The third full day of the Battle of Britain closed with both sides bloodied, neither willing to yield the Channel skies.

HMS Vanessa was disabled by near-misses during Luftwaffe attacks on 13th July and was taken under tow by tug Lady Duncannon for repair, eventually returning to service in November 1940. During Kanalkampf, the Royal Navy sustained notable losses as German dive-bombers and fighters targeted Channel convoys. Between July and mid-August 1940, over 20 merchant ships were sunk and several destroyers, including HMS Brazen and HMS Delight, were lost to air attack. Smaller vessels and escorts also suffered damage, straining naval resources. These losses highlighted the vulnerability of shipping under sustained Luftwaffe assault and underscored the increasing reliance on RAF Fighter Command to provide crucial protection.

July 14th

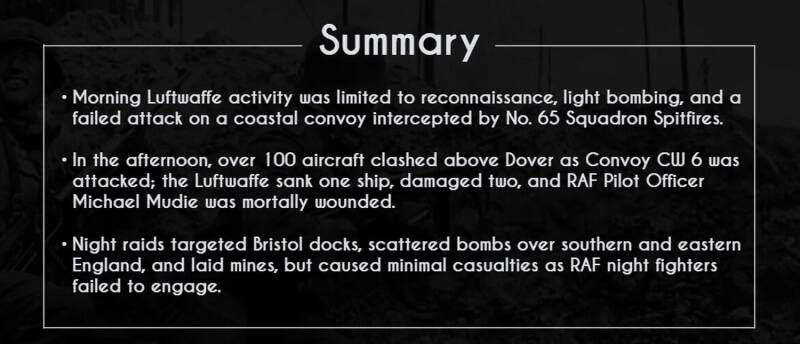

Sunday 14 July broke clear and calm over southern England — perfect for flying, perfect for killing.

The Luftwaffe’s morning was scattered: reconnaissance flights, light bombing, and coastal convoy harassment.

Near Manston, radar spotted a lone Dornier Do 17 with heavy Messerschmitt escort. No. 65 Squadron Spitfires from Hornchurch intercepted, downing one Bf 109 and damaging others.

The convoy passed untouched.

An address given by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill on July 14th 1940.

https://www.battle-of-britain.org.uk/history/battle-of-britain-july-1940-day-by-day

...the chaotic dogfight above Dover...

The main strike came that afternoon.

Convoy CW 6 — “Bread” — off Dover drew over forty Ju 87 Stukas, twenty-plus Do 17s, and swarms of Bf 109s and Bf 110s. RAF squadrons from Biggin Hill, Croydon, and Manston scrambled.

In the chaotic dogfight above Dover — over 100 aircraft locked in combat — the RAF claimed three Stukas and three 109s.

But No. 615 Squadron lost Pilot Officer Michael Mudie, shot down and mortally wounded despite rescue from the Channel.

A British convoy under air attack by German dive-bombers on 14 July 1940. On this day, Luftwaffe operations focused on attacks against Channel convoys. Several raids were launched during the day, with dive-bombing Stukas and fighter escorts targeting merchant shipping. RAF Fighter Command responded with patrols and interceptions, though many encounters were hindered by weather and visibility. Losses were sustained on both sides, but the attacks underscored the German strategy of disrupting Britain’s supply lines and testing RAF defences during the Kanalkampf phase of the Battle of Britain.

...a commentary many found thrilling, others distasteful...

The Luftwaffe damaged two freighters and sank SS Island Queen.

From Dover’s cliffs, BBC reporter Charles Gardner broadcast live, mistaking Mudie’s Hurricane for a falling Stuka — a commentary many found thrilling, others distasteful.

By late afternoon, worsening weather curtailed large raids. Scattered attacks persisted: a Ju 88 fell to anti-aircraft fire; bombers probed eastern England; minor reconnaissance reached Scotland.

The SS Island Queen, one of the victims of the Luftwaffe attack on Convoy CW 6 'Bread' on the 14th July 1940, sinking after being bombed and strafed by German aircraft. Convoy CW 6, codenamed Bread, departed the Thames on 13 July 1940, carrying coal to the West Country. On 14 July, it was heavily attacked in the Channel by Luftwaffe Ju 87 Stukas and bombers during Kanalkampf. Fierce assaults sank or severely damaged several ships, including Cooralea and Hodder. Despite Royal Navy escorts and RAF intervention, the convoy suffered badly. CW 6 became an early demonstration of the vulnerability of slow-moving shipping under concentrated German air attack.

https://www.clydeships.co.uk/view.php?a1Page=2793&ref=50080&vessel=ISLAND+QUEEN#v

...causing explosions and damage...

After dark, He 111s targeted Bristol’s Avonmouth docks and smelting works, causing explosions and damage.

Further raids scattered bombs over Kent, Suffolk, and the Isle of Wight, while minelayers prowled the Thames Estuary and Harwich approaches.

Fires burned in County Durham, but casualties were nil. RAF night fighters hunted in vain through low cloud, as the Luftwaffe slipped back across the Channel.

July 15th

Low cloud and heavy haze throttled air activity, yet the Luftwaffe pressed on with scattered raids.

At dawn on Monday 15th July, Brighton suffered its first wartime strike: a lone raider bombed Kemp Town, damaging homes but causing no casualties.

Soon after, bombers from Luftflotte 3 hit Barry and Pembroke Dock, targeting ports and factories.

Luftwaffe aerial reconnaissance photo of Brighton, 1940. This photograph was produced by the German Luftwaffe (air force) during World War Two. It was almost certainly taken in 1940 as preparations were made for the German invasion of England. The photograph notes defence measures in the area, including the partially demolished piers. Brighton's piers were both broken in the centre due to fears they could be used as landing platforms by German troops. Brighton suffered it's first Luftwaffe attack on July 15th 1940, during Kanalkampf.

...met the attackers head-on...

By early afternoon, the day’s fiercest attacks began.

At 13:41, Mount Batten in Plymouth was struck, followed by raids on Yeovil’s Westland Aircraft works and Yeovilton air base.

Spitfires of No. 92 Squadron and Hurricanes of No. 213 met the attackers head-on, downing one Ju 88 and damaging another.

RAF losses were light, with Yeovil sustaining only minor damage.

Almost simultaneously, bombs disrupted communications at RAF St Athan, Carew Cheriton, and Llandow.

...ensuring the convoy sailed on unharmed...

Mid-afternoon, around ten Do 17s targeted Convoy Pilot in the Thames Estuary.

Hurricanes of No. 56 Squadron intercepted, destroying one bomber, damaging another, and ensuring the convoy sailed on unharmed.

Elsewhere, reconnaissance flights shadowed east coast shipping; one proved deadly when SS Heworth was sunk near Aldeburgh Lightvessel.

As evening fell, Do 17s probed Portsmouth and Southampton, losing one bomber in combat.

Further north, lone aircraft reconnoitred RAF Drem and Aberdeen without attacking.

Night brought limited action: small formations approached between Newcastle and Flamborough Head, and along the Norfolk–Tyne coast, likely laying mines in Liverpool Bay and eastern waters.

One bomb fell near Berwick without casualties.

The day’s fighting was brief, scattered, and shaped by weather — yet it brought Brighton’s first raid, minor RAF damage, and another merchant loss at sea.

The Daily Express dated 15th July 1940, reporting on the RAF successes against the Luftwaffe dive bombers that day. During Kanalkampf, the RAF scored notable successes against German dive-bombers, particularly the Ju 87 Stukas. Designed for precision strikes, the Stukas proved highly vulnerable when confronted by swift and determined RAF fighter patrols. Time and again, Hurricanes and Spitfires tore into their tight formations, inflicting heavy losses and disrupting raids. These engagements showcased the RAF’s growing skill in intercepting enemy attacks and underscored the Luftwaffe’s dependence on fighter escort, foreshadowing the challenges Germany would face in the wider battle.

https://www.militariazone.com/ephemera/daily-express-july-1940-battle-of-britain/itm52037

July 16th

On 16 July 1940, a dense, stubborn fog shrouded much of France, the Straits, and south-east England, muffling the roar of engines and smothering the skies in grey.

With visibility down to a fraction, both sides found their operations strangled.

The Luftwaffe’s activity shrank to a thin trickle—probing flights, weather reconnaissance, and the occasional opportunistic strike.

Even so, there were sudden flashes of action.

...feeding precious data back to the Luftwaffe....

At dawn, a lone German aircraft ghosted in near Bristol, veering out to sea by Swanage.

Its mission was not to fight but to measure the weather, feeding precious data back to the Luftwaffe.

Through the late morning and midday, more solitary plots appeared off Lizard Point and Start Point, searching for convoys that never came within reach.

Over Cardiff, a Heinkel He 111 emerged briefly from the haze, but RAF fighters scrambled in vain - the cloud swallowed their prey whole.

...bore the brunt of the day’s violence...

North-east Scotland bore the brunt of the day’s violence.

Just after 16:00, bombs fell on Peterhead, striking even the prison grounds, while Fraserburgh and Portsoy suffered blasts that rattled harbour walls.

No lives were lost, but the damage was real. Spitfires from No. 603 Squadron caught a He 111 from III./KG 26 over the North Sea and sent it crashing into the waves, its surviving crew adrift in a dinghy.

...awaiting the moment air superiority could be seized...

By late afternoon, the fog loosened its grip over the Solent, allowing a skirmish worthy of the name.

Junkers Ju 88s approached the Isle of Wight, only to be met by Hurricanes from No. 601 Squadron.

Two German bombers plunged into the sea, their mission foiled.

That same day, far from the Channel’s mists, Hitler signed Directive No. 16. Operation Sea Lion was now in motion - the invasion of Britain set upon the horizon, awaiting the moment air superiority could be seized.

17th July