Adlerangriff - The main attack

Setting the stage for Operation Sealion

Adlertag - (“Eagle Day”) - marked the opening of Unternehmen Adlerangriff (“Operation Eagle Attack”), the Luftwaffe’s grand attempt to crush RAF Fighter Command and clear the way for an invasion of Britain.

This phase of the Battle of Britain lasted from 13th August to 6th September 1940

It came directly on the heels of Kanalkampf (10 July–12 August 1940), the earlier phase of the Battle of Britain in which German forces had probed the Channel convoys, tested British responses, and gathered intelligence.

Having bloodied Fighter Command and drawn its squadrons into battle over the sea lanes, Göring and his commanders believed the stage was set for a decisive blow.

A formation of Luftwaffe JU-88's over England. During Adlerangriff—the sustained assault beginning 13 August 1940—the Luftwaffe sought to annihilate RAF Fighter Command. Göring committed Luftflotten 2, 3, and 5 to coordinated strikes on airfields, radar, and aircraft factories. Waves of bombers, escorted by Bf 109s and Bf 110s, crossed the Channel daily in punishing raids. Though devastating in scale, with hundreds of sorties launched, the offensive overstretched German resources. Heavy losses, especially among bombers and Bf 110s, revealed the limits of the Luftwaffe’s strategy.

...destruction was paramount...

The wider context was unmistakable.

On 16 July 1940, Hitler issued Directive No. 16, outlining provisional plans for Operation Sea Lion, the invasion of Britain.

Yet no landing could be contemplated until the Luftwaffe had secured air superiority.

The RAF’s destruction was paramount—not only to prevent it from striking the invasion fleet, but also to deny cover to the Royal Navy’s Home Fleet, which posed the greatest threat to any attempted crossing.

In 1940, colossal battleships like HMS Hood epitomized British sea power, symbolizing the global reach and dominance of the Royal Navy. With its immense size and firepower, the Hood represented a powerful deterrent, serving as the flagship of the Home Fleet. This fleet's very existence profoundly affected German strategy, particularly regarding Operation Sea Lion (the invasion of Great Britain). The presence of the Home Fleet, with its capital ships, meant the German Kriegsmarine could not guarantee control of the Channel, making a large-scale seaborne invasion fundamentally impossible. The threat of the Hood and her counterparts contained the German surface fleet, forcing Germany to rely instead on air and submarine warfare.

https://www.warhistoryonline.com/whotube-2/hms-hood-and-other-ships-in-color.html

...the sheer resilience of Fighter Command...

On 1 August, Göring received Directive No. 17, authorising an all-out assault on British air and sea power.

Preparations for Eagle Day had begun in late July, but poor weather repeatedly delayed the start.

At last, on 13 August 1940, the assault was unleashed. Luftwaffe raids hit airfields and radar stations, inflicting damage and casualties.

Yet faulty intelligence, miscommunication, and the sheer resilience of Fighter Command blunted the impact.

The RAF was bloodied, but not broken. Its vital command and control network remained intact, and squadrons quickly regrouped.

Göring had promised Hitler swift results—days, or at most weeks.

Instead, Adlertag revealed the same misjudgements that had haunted Kanalkampf: overconfidence, flawed planning, and a failure to understand the RAF’s strength.

Eagle Day was intended as the beginning of the end for Fighter Command, but it became the prelude to the Luftwaffe’s frustration and the indefinite postponement of Operation Sea Lion.

German Fuhrer Adolf Hitler (left) and Head of the Luftwaffe, Hermann Goering (right). Under pressure from Hitler, Reichsmarschall Göring rushed Adlertag preparations, making critical mistakes. Göring grossly misjudged the RAF's strength and relied on flawed intelligence that promised the destruction of Fighter Command in just four days. This overconfident timeline, coupled with his distant command from a luxury train, injected fundamental flaws into the entire offensive.

Rare Color Photo of Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) and Hermann Göring (1893-1946) : r/wwiipics

The invasion that never was: Operation Sealion. Unternehmen Seelöwe was the German blueprint for the full-scale invasion of Great Britain, relying on a massive cross-Channel amphibious operation. The invasion plan was never executed because the Luftwaffe was decisively defeated in its fundamental objective: securing air superiority (Luftüberlegenheit) over the RAF during the Battle of Britain. Acknowledging that the unescorted invasion fleet would be destroyed from the air, Adolf Hitler ordered the operation indefinitely postponed in September 1940. Pictured is a German map from 1940-41 of plans for Operation Sealion. In addition to German forces and planned invasion routes, the planner also drew cartoon ships steaming across the English Channel and a stick figure paratrooper over Kent.

Prelude

After Britain and France declared war on Nazi Germany following the invasion of Poland in September 1939, Europe entered nine tense months of stalemate along the Western Front.

This uneasy lull - often described as the “Phoney War”—masked intense planning within the Oberkommando der Luftwaffe (Luftwaffe High Command) and the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (Supreme Command of the Armed Forces).

By October 1939, German strategists had shifted their focus westward, preparing the next decisive campaign.

British troops reading copies of the Army newspaper 'Blighty' outside their dugout, December 1939. The Phoney War (September 1939 – May 1940) was a period of uneasy calm following Britain and France’s declaration of war on Germany after the invasion of Poland. Despite mobilisations, little major fighting occurred along the Western Front. Allied forces manned the Maginot Line, while the Germans prepared for future offensives. Sporadic skirmishes, naval clashes, and propaganda duels marked the months. This lull ended abruptly with the German blitzkrieg in May 1940, shattering the illusion of stalemate.

...shattered Allied defences...

On 10 May 1940, the German offensive—Unternehmen Gelb (Operation Yellow), also known as the Manstein Plan—was unleashed.

This bold and rapid campaign shattered Allied defences.

The Battle of France ended in catastrophe for the Allies: the main French Army was destroyed, while the British Expeditionary Force narrowly escaped through Dunkirk.

Paris fell on 14 June, and within weeks German forces had swept across much of the country.

On 25 June 1940, France formally surrendered, leaving Britain standing alone against Hitler’s war machine.

French artillerymen reloading a heavy artillery piece of 155mm during the Battle of France, 1940. The Battle of France in 1940 starkly revealed the contrast between French and German forces. France relied on static defences like the Maginot Line, dispersed armour, and cautious tactics, while the Wehrmacht concentrated tanks and mobile infantry in fast, decisive thrusts. German use of blitzkrieg, supported by close air power from the Luftwaffe, overwhelmed French command structures. Despite numerical parity in men and tanks, Germany’s speed, coordination, and adaptability shattered French resistance in just six weeks.

...offering surprisingly lenient terms...

With Western Europe neutralised, the attention of both the OKL and OKW shifted across the Channel.

Hitler initially hoped Britain would seek an armistice, offering surprisingly lenient terms, but Winston Churchill’s coalition government refused all overtures.

Frustrated, Hitler issued orders for preparations for an invasion - Operation Sealion.

To make such an assault possible, air superiority had to be secured.

The Luftwaffe was tasked with destroying the RAF, while the Kriegsmarine was ordered to prepare the transport of German forces across the Channel.

Göring promised swift victory from the skies. If the RAF could be crushed, Hitler believed invasion might not even be necessary.

This aerial offensive was codenamed Adlerangriff - Operation Eagle Attack—the campaign that would lead directly into the Battle of Britain.

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Churchill held an attitude of absolute, unyielding defiance toward any German peace overtures in 1940. He firmly rejected negotiations, believing Britain must fight for total victory and viewing any peace offer as a trap designed to secure Nazi dominance over Europe.

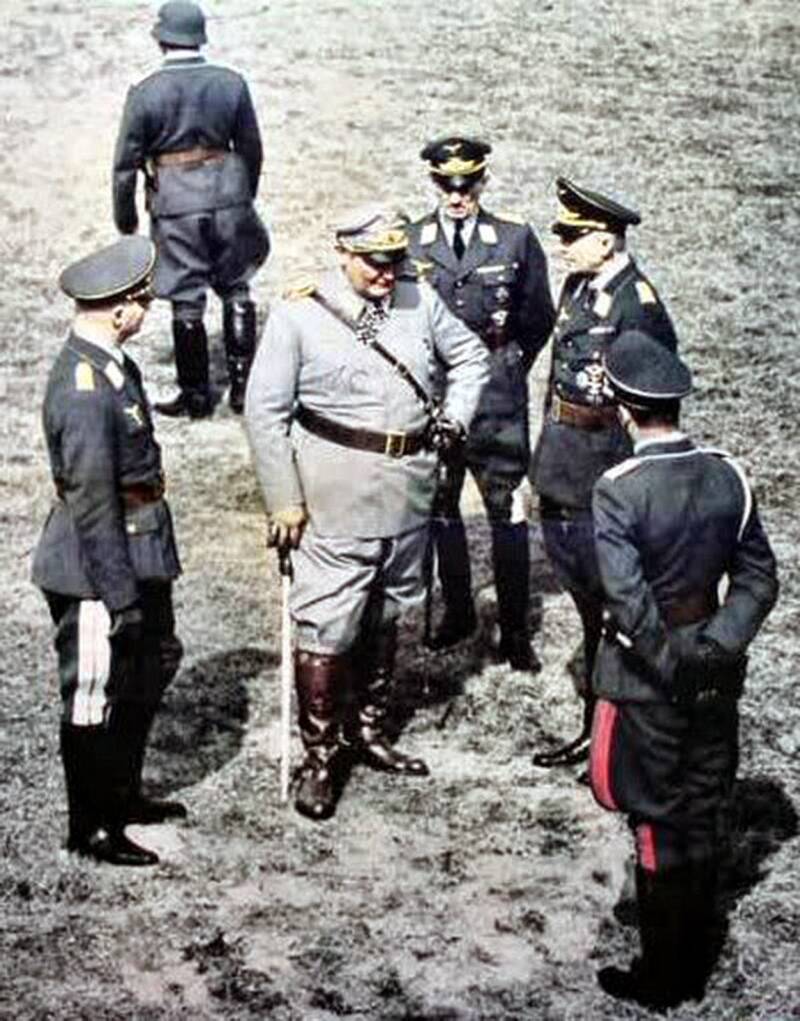

Chief of the Luftwaffe, Hermann Göring and Luftwaffe Generals at Gross-Born. In 1940, Göring made repeated, overconfident promises to Hitler that the Luftwaffe would secure air superiority in days, not weeks. He vowed to decisively destroy RAF Fighter Command and clear the skies for Unternehmen Seelöwe, guarantees that ultimately proved to be based on disastrously flawed intelligence.

From left to right: unidentified Luftwaffe general, Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring (Oberbefehlshaber der Luftwaffe), General der Flieger Gustav Kastner-Kirdorf (Chef des Luftwaffen-Personalamt), and General der Fallschirmtruppe Kurt Student (Kommandierender General der Fallschirmjäger). The picture was taken in May 1942 when Göring visited the Truppenübungsplatz (Training Area) Gross-Born in Pomerania and inspected 2,000 Luftwaffe officers and NCOs for the event of "Kriegsalltag im Deutschen Reich"

World War II in Color: Hermann Göring and Luftwaffe Generals at Gross-Born

The First Phase: Kanalkampf

The Luftwaffe entered the Battle of Britain already weakened by the heavy fighting of the spring campaigns.

During the conquest of France alone, over 1,400 aircraft had been lost, while earlier operations in Poland and Norway during 1939 had cost over 400 machines.

These severe losses forced the German air force into a period of rebuilding before any major assault could be directed against the Royal Air Force.

Only once its strength had returned to an acceptable level did the Luftwaffe begin the first stage of its offensive against Britain.

A Messerschmitt Bf 109E3 1.JG54 White 3 during the Battle of France, May 1940. The Luftwaffe sustained significant attrition during the six-week Battle of France, losing approximately 1,400 aircraft destroyed or seriously damaged—around 30% of its combat strength. Aircrew casualties surpassed 1,100 men, straining the reserves of experienced personnel. While the campaign was a decisive military victory, these heavy losses necessitated a critical period of replenishment and reorganization before the air force could commit to the upcoming Battle of Britain.

Asisbiz Messerschmitt Bf 109E3 1.JG54 White 3 Battle of France May 1940-01

...sought to provoke Fighter Command...

That opening phase, known as the Kanalkampf - the Channel battle - began on 10 July and ran through to 8 August 1940.

It did not initially focus on RAF airfields deep inland, but instead sought to provoke Fighter Command into combat by attacking British Channel convoys.

The logic was straightforward: by drawing the RAF into repeated defensive battles over the Channel, the Luftwaffe hoped to wear down its pilots and aircraft before launching a decisive strike.

Yet in practice, the results were disappointing. In terms of shipping losses, only 24,000 tons were sunk, while minelaying operations proved somewhat more effective, accounting for 38,000 tons.

A British convoy, and shows the ship moving through a sea lane under protection of the British navy. During the Kanalkampf in July 1940, the Luftwaffe aimed to draw out the RAF by targeting convoys in the English Channel. German bombers and fighters attacked coastal shipping, hoping to provoke Fighter Command into engaging under disadvantageous conditions. The campaign combined reconnaissance, bombing, and strafing of merchant vessels and their escorts, disrupting supplies and testing British air defences. While the Luftwaffe inflicted damage on convoys, the RAF largely resisted being lured into large-scale battles, instead using radar and coordinated interceptions. The Kanalkampf thus served as both a training ground and attritional phase ahead of the wider Battle of Britain.

...bloodied but unbroken...

For Fighter Command, the cost was comparatively light.

In July, 74 fighter pilots were killed or went missing, with another 48 wounded, but the overall strength of the RAF actually increased, rising to 1,429 operational aircraft by 3 August.

Shortages remained - 124 pilots below establishment—but these were far from critical.

The Kanalkampf had failed to inflict decisive damage, and the RAF entered August bloodied but unbroken.

A wrecked Hawker Hurricane fighter, 1940. During July 1940, the Royal Air Force suffered significant losses as the Luftwaffe intensified its attacks during the early stages of the Battle of Britain. A total of 74 fighter pilots were killed or went missing, a stark indicator of the intensity of aerial combat over southern England. In addition, another 48 pilots were wounded, either temporarily or seriously, reducing operational effectiveness. These casualties highlighted the immense pressure on Fighter Command and underscored the courage and sacrifice of RAF pilots defending Britain’s skies.

...all marked for destruction...

The second phase of German attacks unfolded between 8 and 18 August.

Shipping remained a target, but now coastal airfields, radar stations, and positions south of London were brought under attack, with raids also reaching as far north as Liverpool under cover of darkness.

On 12 August, the Luftwaffe mounted its first major inland strikes.

RAF stations at Hawkinge, Lympne, and Manston, along with radar stations at Pevensey, Rye, and Dover, were all marked for destruction.

Portsmouth docks were also bombed.

A Heinkel He 111H bombardier points the way to the target, 1940. In early August 1940, the Luftwaffe shifted from the Kanalkampf - attacks on Channel convoys - to Adlerangriff (Eagle Attack), a direct assault on the RAF. German strategy now focused on destroying Fighter Command by bombing airfields, radar stations, aircraft factories, and command infrastructure. This marked a significant escalation in the Battle of Britain, with massed bomber formations heavily escorted by fighters. The aim was to gain air superiority ahead of a planned invasion of Britain. Although initial damage was inflicted, the failure to neutralise RAF command and control allowed Fighter Command to recover and continue resisting German air attacks.

Asisbiz Kanalkampf Heinkel He 111H bombardier points the way to the target Battle of Britain 1940 01

...would fatally undermine the larger offensive...

Yet again, the results proved uneven.

The radar station at Ventnor was badly damaged, and other sites suffered temporary disruption, but by the following morning all were back in operation.

The airfields came under attack but were not destroyed; even Lympne, not an operational station at all, was mistakenly targeted.

Such blunders in intelligence would fatally undermine the larger offensive.

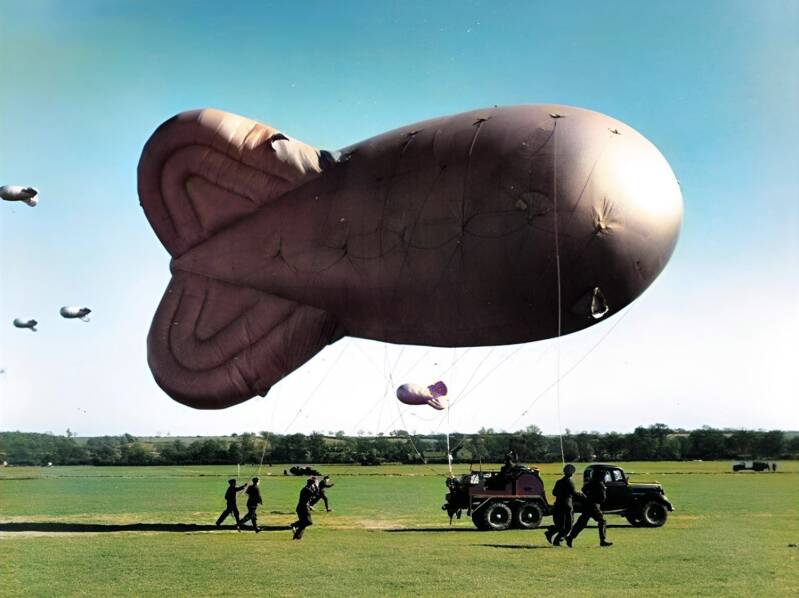

Barrage balloons being used to stop low level attacks Battle of Britain 1940. During the Battle of Britain in 1940, barrage balloons played a key role in defending British cities and airfields from low-level Luftwaffe attacks during Adlerangriff, the German “Eagle Attack” offensive aimed at destroying RAF Fighter Command. Large tethered balloons forced enemy aircraft to fly higher, reducing bombing accuracy and exposing them to anti-aircraft fire. They protected vital targets such as London’s docks, factories, and airfields. While not stopping all raids, barrage balloons disrupted German fighter-bomber tactics, lessening damage during Adlerangriff and contributing to Britain’s resilient air defence network.

Asisbiz Balloons being used to stop low level attacks Battle of Britain 1940-01

...the next and most ambitious stage of the battle...

By 12 August, despite these frustrations, the Luftwaffe believed it was achieving significant results against Fighter Command.

Preparations were finalised for an all-out assault—the operation known as Adlertag, or Eagle Day. German air strength had recovered sufficiently: 71 percent of bombers, 85 percent of Bf 109 units, and 83 percent of Bf 110 units were operational.

With confidence high, the Luftwaffe prepared to launch the next and most ambitious stage of the battle.

Intelligence

Faulty intelligence would lay at the very heart of Adlertag’s eventual failure.

Although the gap between British and German intelligence was not yet overwhelming, the advantage was beginning to tilt decisively in Britain’s favour.

The breaking of the Enigma machine, combined with the Luftwaffe’s poor signals discipline, gave the British unprecedented access to German communications.

The precise impact of Ultra on the Battle of Britain remains debated—official histories long maintained there was no direct influence.

Yet, regardless of that claim, Ultra and the RAF’s Y-Service together built a far more accurate picture of German deployments and intentions than the Luftwaffe ever achieved.

...most dangerous mistakes...

General Joseph "Beppo" Schmid, head of Luftwaffe intelligence in 1940, misjudged RAF strength, underestimated British aircraft production, ignored radar’s significance, and fed Göring flawed assessments that fatally undermined Germany’s Battle of Britain strategy.

At the core of German misjudgement stood Joseph “Beppo” Schmid, commander of the Luftwaffe’s Military Intelligence Branch, Abteilung 5.

His reports throughout this period were riddled with errors.

In July 1940, Schmid both exaggerated the Luftwaffe’s own strength and underestimated the capacity of the RAF.

His most dangerous mistakes concerned radar, airfield identification, and British aircraft production.

Schmid confidently asserted that southern England possessed only a handful of operational airfields.

He claimed Britain could build merely 180–330 fighters per month and predicted that production would soon decline, leaving the RAF unable to withstand a prolonged battle of attrition.

The truth was very different: in July 1940 British factories produced 496 fighters.

...omitted vital details...

Schmid further characterised the RAF as rigid and inflexible, convinced its fighters were tied to home bases and unable to manoeuvre dynamically.

He also omitted vital details about the RAF’s highly effective maintenance and organisation system, which rapidly restored damaged aircraft to service.

Above all, Schmid anticipated only a short campaign and failed completely to mention radar—perhaps his gravest oversight.

The Luftwaffe’s neglect of sustained radar attacks left Britain’s early warning system intact. Radar continued to direct Fighter Command squadrons to intercept raids at precisely the right moments, maximising defensive efficiency.

German intelligence also consistently misidentified airfields, striking stations of RAF Bomber or Coastal Command rather than Fighter Command.

...flawed intelligence...

On Adlertag itself, many of the designated targets, even if destroyed, would have done little to weaken Britain’s fighter defence.

Thus, the Luftwaffe’s grand offensive began from a foundation built on flawed intelligence.

The errors of Schmid and his branch meant that Adlertag’s blows fell wide of the mark, allowing the RAF to fight on with undiminished strength.

RAF Fighter Command

The foundation of Britain’s defence during the Battle of Britain rested on a vast and intricate system of detection, command, and control.

This structure, known as the Dowding System after its architect, Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding, was the beating heart of RAF Fighter Command.

Dowding had taken the framework first laid down by Major General E. B. Ashmore in 1917 and transformed it into a modern, efficient, and highly coordinated network.

Central to his design was the adoption of Radio Direction Finding—radar—at his own insistence.

...remarkable speed and efficiency...

By integrating this revolutionary technology with the keen eyes of the Royal Observer Corps and a meticulous system of information processing,

Dowding created a mechanism that allowed Britain to intercept and respond to incoming German attacks with remarkable speed and efficiency.

The system’s official title - RDF, or Radio Direction Finding - was itself a deliberate act of deception, designed to conceal its true purpose from German intelligence should its existence ever be revealed.

...information flowed to the central hub...

The first warnings of incoming air raids came from the Chain Home radar stations, their towers dotted along Britain’s coastline.

These facilities could often detect Luftwaffe formations as they assembled over French and Belgian airfields, long before they crossed the Channel.

Once the German aircraft moved inland, beyond radar range, the Royal Observer Corps picked up the task of tracking them. From there, information flowed to the central hub of Fighter Command at RAF Bentley Priory.

Every new plot was assessed - was it hostile or friendly? - and the findings passed directly to the main operations room, buried deep within an underground bunker.

...streams of incoming reports...

Inside this nerve centre, teams from the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) converted streams of incoming reports into a visual picture of the battle in motion.

Using telephones, they relayed details of enemy positions, then placed colour-coded counters onto a vast map of Britain, spread across a plotting table marked with a British Modified Grid.

Magnetic rakes pushed these counters across the surface, tracking each raid’s direction, altitude, and strength.

The colour of a counter indicated how recent the information was, ensuring that commanders could instantly judge whether they were working with fresh intelligence or older, less reliable data.

...a clear, real-time picture of enemy movements...

This elegantly simple method gave the Fighter Controllers, and Dowding himself, a clear, real-time picture of enemy movements and possible targets.

From this picture, swift and effective decisions could be made. The system did not rely on radar and visual sightings alone.

Supplementing these were intercepts from the Y Service, which monitored German radio transmissions, and intelligence from Bletchley Park’s Ultra decoders, who were piecing together the Luftwaffe’s order of battle.

Combined, these sources gave Fighter Command the ability to anticipate not only where the enemy was, but often what they intended to do.

...control was exercised at a tactical level...

At the same time as the central plot at Bentley Priory, identical streams of information were transmitted to the Group headquarters, where control was exercised at a tactical level.

Each Group operated its own filter room, where data was cross-checked before being passed into their operations room, also housed within fortified underground bunkers.

Here, the map on the plotting table covered the Group’s specific area of responsibility, showing its airfields, bases, and patrol sectors.

Lines of radio and telephone links carried a constant flow of reports to and from Observer Corps posts, naval stations, anti-aircraft batteries, and the sector airfields themselves.

During Adlerangriff, the WAAF plotters and RAF controllers were the unseen backbone of Fighter Command. Plotters at Bentley Priory and group headquarters swiftly transferred radar and observer data onto plotting tables, tracking incoming raids. Controllers then directed squadrons with remarkable precision, ensuring resources were deployed efficiently. Their rapid coordination, supported by telephone and radio networks, allowed Fighter Command to react instantly to Luftwaffe movements. Without these tireless women and controllers, Britain’s air defences would have been fatally compromised.

...meet the enemy with precision timing...

At the heart of each Group’s control room stood the Duty Fighter Controller, the commander’s personal representative.

It was he who decided when and how each raid would be intercepted, deploying squadrons to meet the enemy with precision timing.

Engineers were always close at hand, ready to repair any break in communications within minutes, ensuring that the lifeblood of the system—the unbroken flow of information—was never cut.

Through this vast web of radar, observers, operators, and controllers, the Dowding System transformed scattered reports into coordinated action.

It was the invisible keystone of Britain’s defence, the quiet architecture behind every interception, and the reason Fighter Command could stand its ground against the full force of the Luftwaffe.

13 August - Adlertag

On Tuesday 13th August 1940, the Luftwaffe launched its long-promised assault on Britain. Adlertag (Eagle Day) was intended as the decisive opening strike that would cripple Fighter Command and pave the way for invasion.

Yet poor intelligence, confused orders, and British resilience turned this planned triumph into a day of costly frustration.

The day before, 12 August, had been billed as a rehearsal. Radar stations at Pevensey, Rye, Dover, and Ventnor were struck, along with airfields at Hawkinge, Lympne, and Manston. Portsmouth docks were also bombed.

Damage was limited: only Ventnor was briefly disabled, while other stations were back in service within hours.

Airfields sustained damage but remained operational, and German intelligence mistakenly identified Lympne as a major fighter base. Intended to blind and weaken the RAF, the raids instead underscored the resilience of Britain’s radar network and repair system.

Adlertag (Eagle Day) - 13th August 1940: On Adlertag, the Luftwaffe launched a massive, coordinated assault to cripple RAF air power. Striking airfields, radar stations, and infrastructure across southern England, they deployed hundreds of bombers and fighters. Poor weather, communication failures, and strong RAF resistance blunted the offensive, resulting in heavy German losses.

...were mauled by Hurricanes and Spitfires...

Adlertag itself began in confusion. Poor weather forced a postponement, but the recall orders failed to reach all units.

At dawn, Dorniers of KG 2 bombed Eastchurch unescorted, devastating hangars, stores, and aircraft—but Eastchurch was a Coastal Command base, not part of Fighter Command.

On their return, the Dorniers were mauled by Hurricanes and Spitfires, losing five aircraft.

Other early raids against Farnborough and Odiham achieved little, with German crews greatly exaggerating their success.

The wreckage of Dornier Do 17Z ‘U5 + DS’ of 8 Staffel./Kampfgeschwader 2 at Seasalter, near Whitstable in Kent. The aircraft was attacked and shot down by Hurricanes of Nos. 111 and 151 Squadrons on 13th August 1940. The flight engineer baled out wounded and was captured. The rest of the crew were killed.

Tuesday 13 August 1940 | The Battle of Britain Historical Timeline

...inflated claims masked the limited damage inflicted...

As morning advanced, coordination faltered. Units of Luftflotte 3 attacked Portland Harbour and Bristol docks, while others bombed minor or misidentified airfields.

Communication failures left formations flying unescorted, and inflated claims masked the limited damage inflicted.

At Portland, a “freie Jagd” of Bf 110s blundered into Hurricanes, losing six aircraft in minutes.

By afternoon, Göring pressed forward. Large raids crossed the Channel aimed at RAF bases and industrial sites.

Ju 87s of StG 77 attacked Detling with devastating local effect, killing 67 personnel and destroying 22 aircraft—but again, the station belonged to Coastal Command, not Fighter Command.

At Southampton, bombs caused fires and damaged infrastructure, while Eastchurch and Rochester were struck again. RAF squadrons scrambled in strength, exacting losses from the attackers.

...a bitter blow...

While the Luftwaffe pressed its daylight offensive, RAF Bomber Command suffered disaster.

Twelve Blenheims sent against Aalborg in Denmark lost eleven aircraft, with only one returning - a bitter blow that darkened the RAF’s own tally for the day.

As night fell, German operations shifted to psychological warfare.

Nine He 111s of Kampfgruppe 100 attempted to bomb the Spitfire factory at Castle Bromwich, but only four crews found the target, causing minor damage.

Other raids struck Belfast, Glasgow, and cities across Britain, destroying five Short Stirlings at Queen’s Island but achieving little else.

Propaganda leaflets, parachutes, and radios were dropped over the Midlands and Scotland to suggest an imminent invasion.

Scattered raids stretched civil defences, but physical damage was limited.

Dornier Do 17Z ‘U5 + KA’ of Stab.Staffel./Kampfgeschwader 2 was shot down over Barham in Kent on 13 August 1940 and ended up crashing onto the Canterbury-Folkestone railway line at Pherbec Bridge. The Dornier bomber crews experienced a brutal initiation on Adlertag, 13th August 13, 1940, the planned start of the main German air offensive. They were tasked with penetrating deep inland to strike RAF airfields, but poor weather and coordination failures led to heavy losses. Flying under intense pressure, the slow, straight-winged Do 17s were vulnerable to fast British fighters. Facing concentrated intercepts from RAF Hurricanes and Spitfires, many Dorniers were shot down, forcing the Luftwaffe to quickly review its tactics for bomber protection.

Tuesday 13 August 1940 | The Battle of Britain Historical Timeline

...it revealed the Luftwaffe’s shortcomings...

By day’s end, the Luftwaffe had flown almost 1,500 sorties against 727 by the RAF. German losses amounted to around 45 aircraft, compared with 15 British fighters.

Severe damage was inflicted at Detling and Eastchurch, but Fighter Command’s vital sector stations remained untouched.

German crews claimed thirty fighters destroyed, but RAF records confirmed only half that number.

Among the day’s losses was Luftwaffe ace Oberleutnant Paul Temme, while British pilots such as Adolph “Sailor” Malan led spirited defences. Adlertag had promised a crushing blow.

Instead, it revealed the Luftwaffe’s shortcomings in intelligence, communication, and coordination. Fighter Command, bloodied but intact, emerged with its defensive system unbroken.

For the Luftwaffe, Eagle Day was not the decisive victory Göring envisaged, but the beginning of a long, grinding battle Britain was prepared to fight.

Messerschmitt Bf 109E-1 of Oberleutnant Paul Temme, Gruppe Adjutant of I/ JG 2 ‘Richtofen’, which crashed near Shoreham aerodrome in Sussex on 13th August 1940. For the Messerschmitt Bf 109 pilots on Adlertag, the day was defined by aggressive dogfighting and the limitations of range. Their primary role was to provide close escort for the slow Dorniers and Ju 88s, which tethered them to the bombers' slower pace. While skilled Luftwaffe aces often outfought their RAF counterparts in skirmishes, the distance to inland targets severely limited the 109s' fuel, forcing quick retreats and leaving the bombers vulnerable during the critical last miles over Britain.

IWM (HU 67701, HU 88398, HU 76146)

Tuesday 13 August 1940 | The Battle of Britain Historical Timeline

14th August

On Wednesday 14 August 1940, poor visibility and heavy cloud curtailed large-scale operations, but the Luftwaffe pressed ahead with scattered raids across southern and western England.

Though less intense than Adlertag, these strikes tested Fighter Command and inflicted local damage. At 11:40 hours, radar picked up a major formation over Calais.

Around eighty Ju 87s from II./StG 1 and IV./LG 1, escorted by 100 Bf 109s, crossed the Kent coast. Hurricanes and Spitfires intercepted, losing three fighters while the Germans lost one Bf 109, its pilot captured near Dover.

A crashed Heinkel He IIIP, 1G+NT, of III/KG 27, shot down by Blue Section of No. 92 Squadron RAF at 6 pm on 14 August 1940, lying by the side of the road at Charterhouse, Somerset. Note the machine gun projecting from the starboard side of the fuselage as protection from beam attacks.

Wednesday 14 August 1940 | The Battle of Britain Historical Timeline

...fought back fiercely...

The Stukas attacked harbour targets, sinking the Goodwin Lightship and destroying barrage balloons.

Minutes later, sixteen Bf 110s of Erprobungsgruppe 210 bombed RAF Manston, destroying hangars, cratering the runway, and wrecking aircraft on the ground.

Anti-aircraft gunners fought back fiercely, downing two of the attackers within the airfield perimeter.

Despite damage, Manston remained operational.

Flying Officer Anthony Eyre, DFC, of ‘B’ Flight, No. 615 (County of Surrey) Squadron, Royal Auxiliary Air Force, is debriefed by his squadron’s Intelligence Officer. On 14 August 1940, he claimed a Ju 87 destroyed and shared in the destruction of another; the following day, he shared in the destruction of a Messerschmitt Bf 109.

Wednesday 14 August 1940 | The Battle of Britain Historical Timeline

...achieving temporary disruption...

In the afternoon, Do 17s struck Pevensey radar station, achieving temporary disruption.

Further raids targeted Middle Wallop, hit four times between 17:07 and 19:35, killing three airmen and a civilian.

Spitfires of No. 609 Squadron intercepted, downing a Ju 88 and a He 111, the latter carrying Oberst Alois Stöckl, Kommodore of KG 55. RAF Andover also suffered, while Southampton’s rail network was disrupted.

A wrecked hanger at RAF Middle Wallop after a German raid on 14 August 1940.

Wednesday 14 August 1940 | The Battle of Britain Historical Timeline

...defences again absorbed the blows...

In the west, He 111s attacked the Bristol Aeroplane Company at Filton but were intercepted by No. 92 Squadron, three bombers destroyed.

Smaller raids struck Whitchurch Airport, Weston-super-Mare, and RAF Sealand, where a He 111 was brought down by training unit pilots.

Night operations were scattered and caused little damage. Berlin itself endured an air raid alarm, though no bombs fell.

The day lacked Eagle Day’s intensity, but Britain’s defences again absorbed the blows and remained unbroken.

The Sergeants’ Mess at RAF Sealand after a Luftwaffe raid on 14 August 1940.

Wednesday 14 August 1940 | The Battle of Britain Historical Timeline

15th August - The Greatest Day

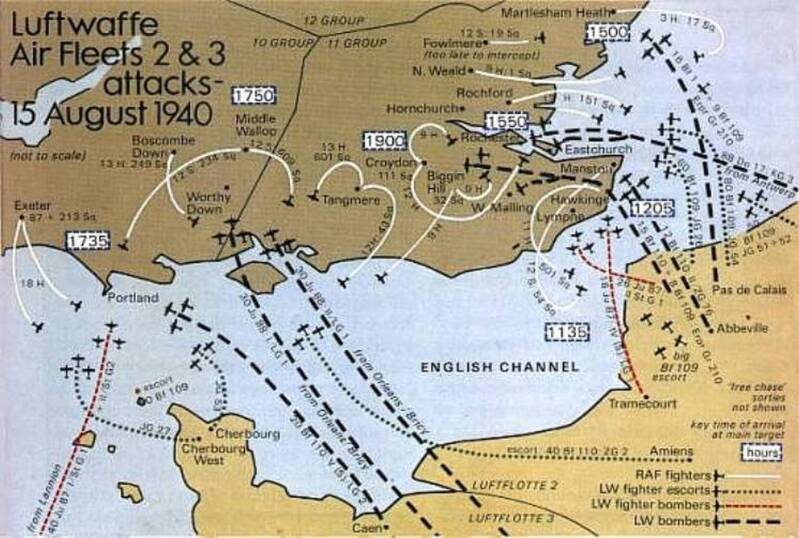

Thursday, 15 August 1940, marked the Luftwaffe’s most ambitious assault of the Battle of Britain.

For the first time, all three German air fleets—Luftflotten 2, 3, and 5—were thrown into a combined offensive.

Nearly 1,800 sorties were flown, more than 500 by bombers. Göring’s directive was clear: destroy the RAF in the air and on the ground, cripple its factories, silence its airfields.

The attacks inflicted damage, yet the price was heavy—seventy-six aircraft lost in a single day, including twenty-six of the prized Bf 110s. Fighter Command endured, bloodied but unbroken.

On 15 August 1940, Luftflotte 2 and Luftflotte 3 spearheaded the Luftwaffe’s main offensive in southern England. Luftflotte 2, under Kesselring, directed mass raids against Kent, Sussex, and the Thames Estuary, hammering airfields like Hawkinge, Lympne, and Biggin Hill. Simultaneously, Luftflotte 3, led by Sperrle, struck Hampshire, Wiltshire, and Dorset, with attacks on Middle Wallop, Worthy Down, and Portland. Despite heavy bombing and widespread disruption, RAF squadrons fought fiercely, inflicting punishing losses that blunted the German advance.

http://www.arborfield-september49ers.co.uk/

...an omen of the battles to come...

The day opened at 04:50 when a Dornier Do 17, sent to photograph southern airfields, was intercepted south of Ventnor by Spitfires of No. 152 Squadron.

It was shot down before completing its task—an omen of the battles to come.

At mid-morning, forty-five Ju 87 Stukas, escorted by JG 26 fighters, dived on Hawkinge and Lympne. Hurricanes of No. 501 Squadron and Spitfires of No. 54 Squadron intercepted, downing several attackers, yet the bombers pressed through.

Lympne was wrecked—buildings destroyed, power and telephone lines cut, the station unusable for forty-eight hours.

Hawkinge was hit but quickly recovered. Radar coverage briefly faltered as power lines to Rye, Dover, and Foreness stations were severed.

...defensive circles of Bf 110s were picked apart...

Around midday, Luftflotte 5 struck from Norway in its only major daylight raid of the battle.

Sixty-five He 111s and thirty-four Bf 110s advanced on northern airfields, led by Hauptmann Werner Restemeyer.

But British radar detected them early, and No. 13 Group scrambled Spitfires and Hurricanes from Acklington, Usworth, and Tyneside.

The formation broke apart under pressure. Bombs were jettisoned into the sea, while defensive circles of Bf 110s were picked apart.

Restemeyer’s aircraft exploded when its belly tank ignited, plunging into the North Sea. Eight Heinkels and six Bf 110s were destroyed—losses so severe that Luftflotte 5 abandoned daylight operations entirely.

Hawker Hurricanes (P3059 and P3208) of No. 501 Squadron take off from RAF Hawkinge on a squadron patrol, 15 August 1940. Three days later, both these aircraft would be shot down and destroyed in combat between Canterbury and Whitstable. Hawker Hurricanes formed the backbone of Fighter Command’s defence. Heavily engaged across both northern and southern England, they bore the brunt of Luftwaffe attacks. In fierce dogfights, Hurricanes intercepted bomber formations, often outnumbered yet inflicting heavy losses. From Kent to Tyneside, they disrupted raids, destroying Heinkels and Bf 110s at great cost. Though many were lost, their rugged design, firepower, and the skill of their pilots proved vital in preserving Britain’s aerial shield.

https://battleofbritain1940.com/entry/thursday-15-august-1940/

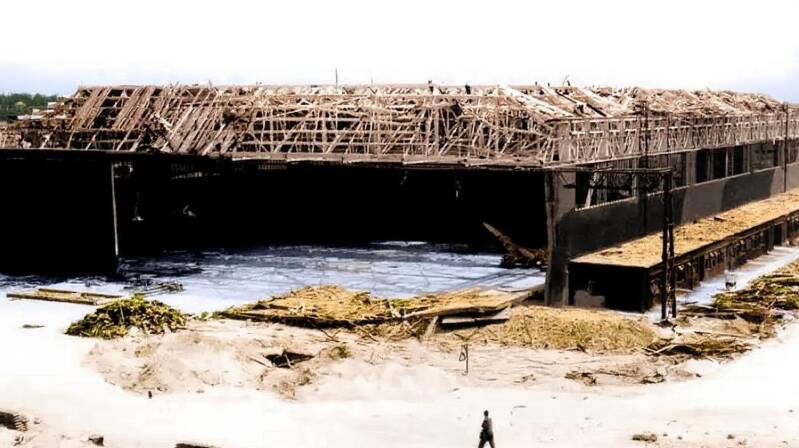

...demolishing workshops and hangars...

At 13:30, fifty Ju 88s of KG 30 bombed RAF Driffield despite interceptions by Hurricanes, Spitfires, and Defiants.

Four hangars and three buildings were destroyed, seven Whitleys lost, six RAF personnel killed. Anti-aircraft fire and fighters downed six of the bombers.

An hour later, eighty-eight Do 17s of KG 3, heavily escorted, crossed from Belgium. Despite fierce resistance, many broke through.

The Short Brothers factory at Rochester was hit hard - six Stirling bombers destroyed, production halted.

At Martlesham Heath, Bf 110s of Erprobungsgruppe 210 struck low, demolishing workshops and hangars.

British troops guard the burning remains of a Junkers Ju 88 of the KG 30, one of seven aircraft shot down during attacks on airfields in Yorkshire on 15th August 1940. Spitfires of No. 616 Squadron and Hurricanes of No. 73 Squadron intercepted the enemy formation as it approached the coast near Scarborough.

...they paid dearly...

At 17:00, Luftflotte 3 sent 250 aircraft across Hampshire and Wiltshire.

Middle Wallop was lightly hit, while Worthy Down and Portland suffered only minor damage.

Eleven RAF squadrons joined battle. Twenty-five German aircraft were destroyed against sixteen RAF fighters, including three - possibly four - 109's and 110s claimed in quick succession by Belgian pilot J. Phillipart of No. 213 Squadron.

At 18:50, Croydon endured its first heavy raid. Bf 110 fighter-bombers of Erprobungsgruppe 210, their escort peeled away, struck factories and workshops, causing over eighty casualties and wrecking training aircraft.

Yet they paid dearly—six Bf 110s and a Bf 109 were shot down by Nos. 111 and 32 Squadrons.

Belgian RAF pilot Jacques Philippart who destroyed several German aircraft on the 15th August.

Messerschmitt Bf 110 D-0/B (S9+CK), W.Nr. 3341, of 2.Staffel/Erprobungsgruppe 210, force-landed at Hawkhurst in Kent following the late-afternoon raid on Croydon airfield on 15 August 1940. The starboard rudder controls had been shot through during the action, leading pilot Oberleutnant Alfred Habisch to believe the aircraft might become uncontrollable before reaching the French coast. Choosing not to risk the lives of himself or his rear gunner/radio operator, Unteroffizier Ernst Elfner, he made the decision to put the aircraft down safely in England. Both men were taken prisoner.

https://battleofbritain1940.com/entry/thursday-15-august-1940/

...suffered its heaviest losses...

Scattered raids continued into the night, reaching as far as Liverpool and Birmingham, but with little effect.

The true battle had been fought in daylight.

By nightfall, the Luftwaffe had suffered its heaviest losses of the campaign so far.

The RAF’s southern airfields were battered but operational; radar remained intact.

In the north, Luftflotte 5’s defeat was decisive. Göring’s grand plan to crush Fighter Command in a single coordinated blow had failed.

...bloodied, but unbroken...

Major Adolf Galland later recalled:

“We saw one comrade after the other vanish from our ranks… Not a day passed without a place remaining empty at the mess table.”

The Greatest Day proved that the RAF could withstand the combined weight of the Luftwaffe. Fighter Command stood bloodied, but unbroken.

A Junkers Ju 87B (L1 + EV) of 10 Staffel./Lehrgeschwader 1 lies wrecked in a garden at 78-82 Shorncliffe Crescent in Folkestone. This aircraft was on a bombing sortie over the Channel on 15 August 1940 when it was hit by AA fire and Hurricanes from No. 501 Squadron. Flying at low level, the Stuka hit high tension cables causing it to crash into houses and burn out, killing both crew members (pilot Uffz Franz-Heinrich Kraus and gunner/observer Uffz Herman Weber).

https://battleofbritain1940.com/entry/thursday-15-august-1940/

16th August

The morning air was warm and still, with haze drifting over the Channel—an ominous calm before one of the fiercest days of aerial warfare yet.

By midday, the Luftwaffe launched a series of coordinated strikes that tested Fighter Command to its breaking point. At 12:00 hours, radar picked up large formations heading for Kent.

Around 100 Dornier Do 17s of KG 2, escorted by Bf 109s from JG 51, targeted the Thames Estuary and inland airfields like Biggin Hill and Kenley. RAF squadrons scrambled to intercept.

In the chaos, Flight Lieutenant Henry Ferris collided with a Dornier - both aircraft were lost.

Squadron Leader Rodney Wilkinson’s Spitfire collided with a Bf 109 flown by Unteroffizier Ernst Buder; Buder bailed out and was captured, but Wilkinson was killed.

...skies over Kent erupted...

The skies over Kent erupted as RAF fighters clashed with bombers and their escorts. Ten German aircraft were downed, but six RAF fighters were lost. Hauptmann Walter Oesau of JG 51 claimed two Spitfires, raising his tally to eighteen.

On the ground, West Malling was bombed again, forcing its closure until 20 August.

Civilian casualties mounted: Tilbury docks were hit, and at Northfleet, Bowater’s Paper Mills suffered a direct strike—25 killed, 32 injured.

At 13:00, a new wave crossed from Cherbourg—150 aircraft including Ju 87 Stukas of StG 2, Ju 88s of KG 54, and heavy fighter escort.

Over Nab Tower, the formation split: Ventnor radar, Portsmouth, Gosport, and Tangmere were all targeted.

RAF Hurricanes and Spitfires engaged fiercely. Though RAF pilots claimed 17 Stukas, Luftwaffe records confirmed nine losses.

...he survived and was awarded the Victoria Cross...

Tangmere was devastated. Dive-bombers destroyed aircraft and infrastructure; twelve personnel were killed.

Pilot Officer Billy Fiske of No. 601 Squadron, an American volunteer, crash-landed his burning Hurricane and was pulled from the wreckage.

He died the next day, becoming the first American combat fatality in RAF service.

At 13:10, Ju 88s struck Tangmere again with precision, destroying more aircraft and buildings.

Second Lieutenant E.P. Griffin of the Royal Engineers downed a Bf 110 with a Lewis gun. Gosport and Lee-on-Solent were also bombed—dozens of aircraft wrecked, 21 killed.

Ventnor radar was hit once more, silencing it until late September.

At 13:45, Flight Lieutenant James Nicholson of No. 249 Squadron was wounded and his cockpit ablaze, yet he pressed home an attack before bailing out.

Mistakenly shot by a Home Guard volunteer while descending, he survived and was awarded the Victoria Cross—the only Fighter Command pilot to receive it during the war.

Billy Fiske was a former Olympic bobsled champion and financier who joined the RAF as a volunteer before the U.S. entered the war. Flying Hurricanes with No. 601 Squadron, he was mortally wounded during a raid on Tangmere on 16 August 1940. He became the first American combat fatality of the Battle of Britain.

https://masonandsons.com/blogs/the-periodical/billy-fiske-the-american-who-died-for-england

...Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few...

Evening raids continued. Heinkels struck Heathrow, Wimbledon, Essex, and Eastbourne. Farnborough and Harwell were bombed, and Brize Norton was hit again.

Manston was dive-bombed. By nightfall, scattered attacks reached Brough, Filton, Cardiff, and South Wales.

Fighter Command lost 23 aircraft and nine pilots.

The Luftwaffe lost 44 aircraft and 55 aircrew.

Churchill, observing from RAF Uxbridge, later immortalised the day with his words: “Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.”

17th August

After five days of relentless combat, the skies over southern England fell quiet on 17 August. Fighter Command remained on high alert, but radar screens stayed still.

Squadron Leader Mike Crossley of No. 32 Squadron called it “an amazing, heavenly day”—free from alerts, scrambles, and dogfights. The lull was genuine.

German bomber units, especially KG 3, were exhausted.

Morale was fraying.

Oberfeldwebel Manfred Langer recalled the futility of repeated missions with high losses and little impact: “Man is not a machine, though our commanders thought differently.”

...redeployed to strengthen southern defences...

Fighter Command used the pause to regroup. Repairs resumed at Biggin Hill, Hornchurch, and Kenley.

Reinforcements arrived: No. 310 (Czechoslovak) Squadron at Duxford, No. 1 (Canadian) Squadron joined the fight, and others redeployed to strengthen southern defences.

Luftwaffe activity was limited to scattered reconnaissance. Aircraft shadowed convoys along the East Coast and probed southern airfields.

A lone German plane dropped propaganda leaflets over Welshpool.

Another was downed by the Royal Navy in the Channel.

Despite claims by Luftwaffe aces—including Oesau, Tietzen, and Bär—RAF records show no fighter losses.

...offered no true reprieve...

Nightfall brought renewed action. Small formations crossed the Thames Estuary and Norfolk coast. Between 23:00 and 03:00, bombers struck Birmingham, Coventry, Liverpool, and Avonmouth.

A Ju 88 was intercepted and destroyed off Spurn Head by No. 29 Squadron. X-Gerät-guided raids targeted Castle Bromwich, but most bombs missed.

One Heinkel crashed at Dinard; its crew survived.

Though quieter than previous days, 17 August offered no true reprieve. Both sides regrouped, recalibrated, and prepared for the next wave.

The RAF repaired and reinforced.

The Luftwaffe, strained and frustrated, began to feel the limits of its campaign.

18th August

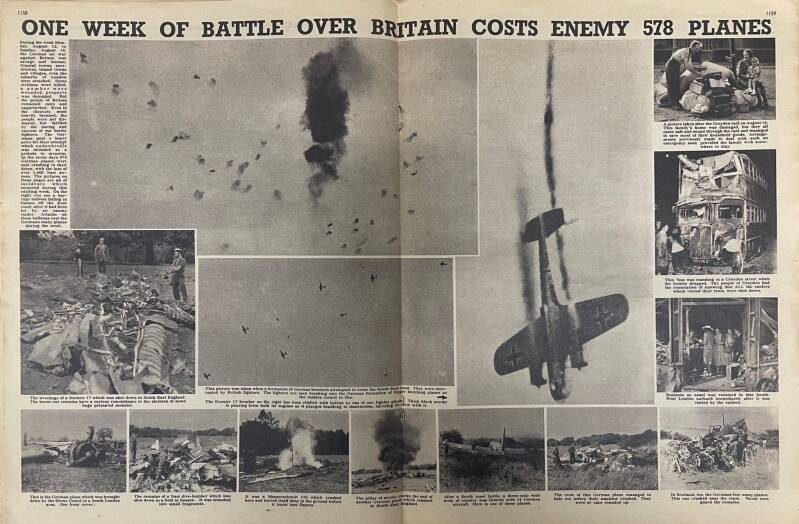

On Sunday, August 18, 1940, the skies over southern England erupted in a maelstrom of violence, a day that would become known as "The Hardest Day" of the Battle of Britain.

The title was earned not from a single, epic dogfight, but from the brutal intensity of the Luftwaffe's operations and the staggering losses on both sides.

Driven by Reichsmarschall Göring’s directive, Luftflotten 2 and 3 launched a massive, coordinated assault aimed at crippling RAF Fighter Command's airfields and clearing the way for a cross-Channel invasion.

Over 850 sorties were flown, targeting critical airfields and radar stations, yet by nightfall, not a single sector station had been knocked out.

The cost to the Luftwaffe was immense: 67 aircraft destroyed and 97 airmen killed or captured.

...a systematic effort to test British defences...

The first blood of the day was drawn in the pre-dawn hours.

A German Junkers Ju 88 from NJG 1 was intercepted and shot down by a British Bristol Blenheim night fighter, its three crewmen becoming the first casualties of a day destined for carnage.

As daylight broke, German reconnaissance intensified.

A Messerschmitt Bf 110 was shot down at an altitude of 31,000 feet by Spitfires from No. 66 Squadron, the first daylight loss for the Luftwaffe that day and the highest recorded interception of the campaign.

These probing flights, operating from 20,000 to 25,000 feet, were a systematic effort to test British defences and pinpoint targets for the day's main assaults, which were already forming up on airfields across northern France.

...most ferocious assault...

The most ferocious assault was directed at RAF Kenley, a vital sector airfield.

The Luftwaffe’s plan was a complex, three-phase strike by Kampfgeschwader 76 (KG 76), involving dive-bombers, medium-level bombers, and a daring low-level surprise attack.

However, war rarely goes to plan.

Thick cloud over France delayed the main formations, and Hauptmann Joachim Roth’s low-level group of nine Do 17s, unaware of the delays, arrived first and alone.

As Roth’s Dorniers swept in at treetop level, they were met by a hail of fire from No. 111 Squadron’s Hurricanes and ground defences.

Though they pressed home their attack, destroying three hangars and several aircraft on the ground, the cost was severe.

...a daring head-on attack that shattered the German formation...

Five of the nine bombers were lost, and only one returned undamaged.

The attack claimed the life of Flight Lieutenant S.D.P. Connors of No. 111 Squadron, whose Hurricane was hit by anti-aircraft fire.

Ten minutes later, the main bomber formations arrived, flying into skies already thick with smoke and flak.

They were immediately engaged by squadrons like No. 32 and No. 64. Squadron Leader Michael Crossley of No. 32 Squadron led a daring head-on attack that shattered the German formation.

The Luftwaffe’s escort fighters were also caught in a melee, and while they inflicted losses on the RAF, they also took heavy casualties.

The final German bomber wave, a group of Ju 88s, found the airfield so obscured by smoke that they diverted to RAF West Malling.

Despite the damage, Kenley’s operations room remained intact and flying operations resumed later the same day.

Soldiers pick amongst all that is left of a Junkers 88 aircraft, shot down at Church Farm, Aylesford, Kent on August 18 1940. The plane has been comprehensively smashed to pieces with only the main wing-spar identifiable in this photo.

Photos reveal clean-up operation in Blitz-struck Britain | Daily Mail Online

...particularly heavy casualties...

At 14:00, the Luftwaffe launched its most ambitious attack of the day, targeting coastal airfields and the Poling radar station.

The assault was led by over 100 vulnerable Ju 87 Stuka dive-bombers.

They struck RAF Ford, RAF Thorney Island, and RNAS Gosport, inflicting significant damage to facilities and aircraft on the ground, with particularly heavy casualties at Ford.

Simultaneously, a group of Stukas attacked the Poling radar station, destroying two transmission pylons and knocking the site out of commission.

The Stukas’ lack of close fighter escort made them easy targets for the RAF.

Hurricanes from Nos. 43 and 601 Squadrons tore into the formations, shooting down ten of the 28 bombers from one group alone.

This brutal toll exposed the Ju 87’s vulnerability, and August 18, 1940, marked its last major appearance in a daylight raid over Britain.

...a fierce dogfight broke out...

As the day waned, the Luftwaffe mounted its final major assault, targeting North Weald and Hornchurch with a force of 250 aircraft.

The Heinkel bombers headed for North Weald but were forced to turn back due to low cloud cover.

Their retreat was met by a determined RAF response, which inflicted further losses.

Over Hornchurch, a fierce dogfight broke out between RAF Hurricanes and German Bf 109s, with both sides taking heavy casualties, including the death of Horst Tietzen, a 20-victory German ace.

...marked a turning point...

Sunday, August 18, 1940, was the costliest day of the campaign for the Luftwaffe.

They failed to put any RAF sector station out of action, a clear sign of Fighter Command’s resilience.

The day marked a turning point, exposing the Ju 87’s weakness and the limits of the Luftwaffe’s ability to coordinate large, multi-phase assaults.

Fighter Command had endured its hardest day, taking a brutal pounding but remaining in the fight.

19th August

Monday the 19th August 1940, marked a pivotal day of strategic change for the Luftwaffe.

Following the devastating losses of "The Hardest Day," a frustrated Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring convened a critical conference at Karinhall.

His top priority was a sweeping reassessment of tactics to reduce bomber losses and preserve his force.

...a humiliating demotion...

In a controversial move, Göring ordered the immediate withdrawal of the vulnerable Junkers Ju 87 Stuka dive-bombers from frontline operations, a humiliating demotion for a weapon that had dominated earlier campaigns.

More controversially, he mandated that the agile Bf 109 fighters abandon their "free-hunting" tactics and act as close escorts for slower bomber streams, a decision that drew immediate scorn from the fighter pilots.

To improve leadership, Göring also purged older, less effective commanders, replacing them with a new generation of younger, more aggressive officers.

...sporadic and scattered...

While these strategic changes were being enacted, the day's combat was sporadic and scattered.

The morning saw only isolated reconnaissance flights, but the afternoon brought a series of small, ineffectual raids across southern and eastern England.

The most significant attack targeted oil storage tanks near Pembroke Docks, destroying ten tanks and causing a major fuel loss.

Elsewhere, bombs fell on airfields and civilian areas, including Chelmsford and Honington, causing casualties and limited damage.

RAF squadrons, though not facing a major assault, were active and successful in intercepting many of the raids.

...a new, more precise era of night bombing...

As night fell, the war entered a new phase.

Instead of mass raids, dozens of single German aircraft conducted uncoordinated attacks, dropping bombs randomly.

However, a technologically significant raid was conducted by KGr 100, which used the advanced X-Verfahren radio navigation system for a precision attack on the Bristol Aeroplane Company.

This marked a new, more precise era of night bombing and a clear shift in Luftwaffe strategy, proving that even a quiet day on the surface could be a turning point in the air war.

20th August

Tuesday, August 20, 1940, brought a welcome respite from the brutal air battles of the preceding days.

Under a blanket of overcast skies, Luftwaffe operations were significantly reduced, constrained by both operational fatigue and deteriorating weather.

However, this lull was deceptive, with isolated raids and reconnaissance flights still keeping Fighter Command on constant alert.

...a few dramatic moments...

Despite the quiet, a few dramatic moments punctuated the day.

A sharp strike by Bf 110s from Erprobungsgruppe 210 on Martlesham Heath met with fierce resistance, and a Dornier Do 17 patrol over the North Sea was intercepted by No. 242 Squadron, costing the life of a young Hurricane pilot, Midshipman P.J. Patterson.

In a more bizarre event, a Focke-Wulf Condor on a reconnaissance mission crashed in neutral Ireland, becoming the first German airmen interned by Irish authorities.

The afternoon also saw a significant development over Kent, where a pilot named Leutnant Heinz Bär of JG 51 claimed his fifth aerial victory, earning the prestigious status of "ace."

...the nation's immense debt...

Later in the day, a new force entered the fray. No. 302 (Polish) Squadron, newly declared operational, flew its first combat sortie over the Yorkshire coast, successfully shooting down a Ju 88 and capturing its crew.

As the pilots fought their daily battles, Prime Minister Winston Churchill stood before Parliament. Reflecting the nation's immense debt to the men of Fighter Command, he delivered one of his most famous lines:

"Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few."

This powerful tribute captured the spirit of the day and cemented the pilots’ legacy in British memory forever.

21st August

Wednesday, August 21, 1940, was a day of relentless, if scattered, conflict.

Poor weather and low visibility hampered large-scale Luftwaffe operations, but the air war continued unabated, with reconnaissance probes and small-scale raids hitting targets across a wide front.

Fighter Command remained on high alert, correctly anticipating that the threat would come in smaller, more elusive forms.

...a robust defensive screen...

British radar stations detected a formation of Dornier Do 17s approaching Norfolk, but No. 242 Squadron quickly engaged, breaking up the attack and forcing the bombers to seek refuge in the clouds.

Meanwhile, a coastal convoy in the Dover Straits came under sustained attack from both artillery and bombers, but a robust defensive screen of barrage balloons and anti-aircraft fire forced the Germans to jettison their bombs prematurely.

The most damaging raid of the day struck a Coastal Command airfield at RAF St. Eval in Cornwall. Junkers Ju 88s from KG 30 launched a brutal attack, destroying six Blenheims on the ground and setting hangars ablaze.

RAF fighters scrambled, but they arrived too late to prevent the destruction.

...a constant, grinding struggle...

The day's combat was a true war of attrition. At Middle Wallop, a Ju 88 was shot down, and over Ipswich, a Hurricane pilot downed a Dornier before being severely damaged.

Even as night fell, the fighting continued, albeit with fragmented and largely ineffective raids.

The day was not one of large, decisive battles, but a testament to the new reality of the Battle of Britain - a constant, grinding struggle fought not just by pilots, but also by every civilian on the ground.

22nd August

On August 22, 1940, squally weather limited the Luftwaffe's large-scale operations, but a steady stream of smaller attacks continued.

The day's first major engagement saw a German artillery barrage and a subsequent bomber raid target Convoy Totem in the Strait of Dover.

Despite intense fire, the convoy escaped, but a Spitfire pilot was tragically killed.

...rendered the airfield temporarily unserviceable...

Later, a raid on Manston Airfield proved more successful for the Germans, who destroyed two hangars and rendered the airfield temporarily unserviceable.

During the attack, two British pilots were killed or wounded in intense dogfights.

Meanwhile, the newly formed No. 302 (Polish) Squadron flew its second combat mission, with its presence serving as a powerful symbol of Allied unity.

...scattered but relentless actions...

As night fell, the war entered a new phase. German bombers, largely grounded during the day, conducted widespread single-aircraft raids across the country.

A precision attack on the Bristol Aeroplane Company at Filton used the advanced X-Verfahren navigation system, signalling a new, more accurate era of night bombing.

The day's scattered but relentless actions - from a sinking merchant ship to a symbolic first bombing of London - showed that even on a "quiet" day, the Battle of Britain was a brutal and continuous fight.

St Barnabas Church, Barton, after a Luftwaffe raid on the 22nd August 1940. Luftwaffe attacks in 1940 caused widespread damage to British churches, many of which stood near docks, railways, or dense housing targeted in raids. London lost numerous historic churches, including several by Wren, while Southwark Cathedral’s damaged nave became an early symbol of the Blitz. Cities such as Liverpool, Bristol, and Plymouth saw similar losses. Churches that survived often hosted relief work or open‑air services, turning damaged buildings into markers of endurance and community resilience.

Doyle Collection Battle of Britain 1940 | The Dover Historian

23rd August

Friday the 23rd August, 1940, was a day of persistent grey skies and scattered raids, a brief respite from the massed battles that had raged for weeks.

Poor weather and thick cloud cover severely restricted Luftwaffe operations, yet isolated raids still caused significant destruction.

One German aircraft penetrated deep inland to Rugby and Warwick, dropping bombs and strafing civilians, a chilling example of the war’s reach.

The day also marked a significant moment for the Allies: Canadian pilots of No. 1 RCAF Squadron flew their first combat mission, a powerful sign of international solidarity.

...demonstrating a new threat...

As the day wore on, a new and dangerous tactic emerged at sea. German Heinkel He 115 torpedo bombers sank two ships in the Moray Firth, demonstrating a new threat to Britain’s vital maritime supply lines.

When night fell, the war entered a new phase. German night raids, though not as widespread as the previous night, were more concentrated.

They struck industrial centers in Bristol and Birmingham, with bombs falling on docks, factories, and residential areas, causing widespread damage and casualties.

...a foreshadowing of the coming Blitz...

In a symbolic first for the capital, bombs fell on Harrow and Wealdstone, an area considered a part of London, a foreshadowing of the coming Blitz.

On the home front, Prime Minister Winston Churchill officially changed the name of the Local Defence Volunteers to the Home Guard, providing a new identity for the citizen soldiers now preparing to defend their homes from a potential invasion.

The day was not one of great air battles, but it was a day of profound, devastating, and far-reaching impacts on the British people.

On 23 August 1940, No. 1 Squadron RCAF entered combat for the first time, becoming the only Canadian squadron to fight in the Battle of Britain. Just over two months later, on 30 October 1940, the surviving pilots gathered at Prestwick for a formal photograph beside one of their Hurricanes. The squadron had arrived in Britain in June and, after a short work‑up, proved itself quickly. Renumbered 401 Squadron in 1941, it later became the highest‑scoring fighter unit in the RAF’s 2nd TAF. The photograph notably includes five Montréal pilots standing together.

Imperial War Museum THE CANADIANS — In the Battle of Britain — Vintage Wings of Canada

24th August

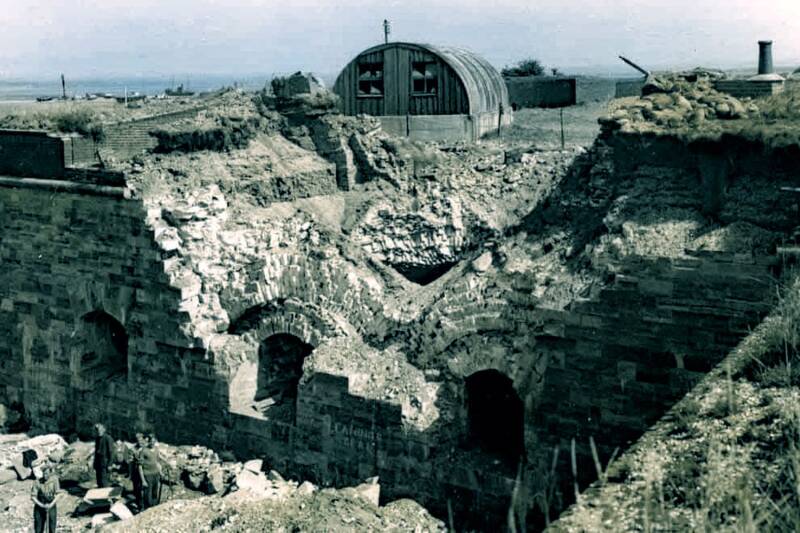

Saturday the 24th August 1940, marked a brutal and decisive turning point in the Battle of Britain.

After a brief lull, both sides were left with a grim tally of losses, yet Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring had failed to achieve the decisive victory he had promised Adolf Hitler.

Under immense pressure, Göring issued a new directive: Fighter Command was to be worn down through a relentless campaign of attacks on airfields and the aircraft industry.

This new, rigid tactic, which forced German fighters to remain close to their bombers, was intended to force a final, decisive aerial battle.

The result was a day of stepped raids, feints, and massed assaults that stretched Fighter Command to its breaking point.

...the incredible feat of becoming an ace in a single day...

Pilot Officer Antoni Głowacki was a Polish fighter pilot who became a legendary "ace-in-a-day" during the Battle of Britain. Flying with No. 501 Squadron on the 24th August 1940, he shot down five German aircraft in a single sortie, a remarkable feat.

https://polishholokaust.blogspot.com/2022/08/tego-dnia-24-sierpnia-1940-roku-w.html

The day's fighting began at first light, with waves of German bombers and fighters approaching the Kent coast. RAF squadrons, including Spitfires of No. 610 Squadron and Hurricanes of No. 615 Squadron, were scrambled to meet the threat.

A brutal running battle developed over East Kent, where Boulton Paul Defiants of No. 264 Squadron proved particularly vulnerable to the agile Bf 109s.

The squadron suffered heavy losses, including their commanding officer, Squadron Leader Philip Hunter.

In a separate engagement, Polish Pilot Officer Antoni Głowacki of No. 501 Squadron achieved the incredible feat of becoming an ace in a single day, claiming five kills.

Despite the fierce fighting, the sustained attacks succeeded in heavily damaging Manston airfield, forcing its temporary closure and marking a tactical victory for the Luftwaffe.

...the war entered a terrifying new phase...

The afternoon brought more terror for the British people.

A major raid on Portsmouth devastated the city, resulting in over 100 civilian deaths and 300 wounded, the single heaviest loss of life on the ground to date.

As night fell, the war entered a terrifying new phase. A large formation of German bombers, off course for their intended target, accidentally dropped their bombs on East London.

This unintentional strike was the first widespread bombing raid on the capital.

Elsewhere, night raids struck industrial centers in Bristol, Birmingham, and other cities.

Chelsea Road, Southsea, on 24th August 1940 after a Luftwaffe raid. The Luftwaffe launched a major attack on Portsmouth, targeting the vital naval dockyard. This raid was part of a shift in German strategy, moving away from purely RAF airfields towards urban and industrial centers. The heavy bombing caused significant damage across the dockyard and surrounding residential areas, resulting in substantial civilian casualties and intensifying the Battle of Britain’s impact on coastal cities.

The News Portsmouth Photo: The News archive 16 spectacular photos capture life in Portsmouth in 1940s

...convinced Adolf Hitler to change his strategy...

The day was costly for both sides. The RAF lost 20 aircraft and 10 pilots, while the Luftwaffe lost at least 41 aircraft.

While key airfields and cities suffered significant damage, the German toll was so heavy that it convinced Adolf Hitler to change his strategy.

Winston Churchill’s swift order for a retaliatory raid on Berlin sealed the course of events, transforming the conflict from a tactical air campaign into the full-scale Blitz.

The 24th August 1940, had demonstrated both the resilience of Fighter Command and the Luftwaffe's shift towards sustained terror bombing, but ultimately, the RAF remained bloodied but unbroken.

An air gunner of No. 264 Squadron RAF about to enter the gun turret of his Boulton Paul Defiant Mk I at Kirton-in-Lindsey, Lincolnshire, August 1940. The Boulton Paul Defiants of No. 264 Squadron proved tragically vulnerable during the intense combat of August 1940. While designed as a day-fighter relying on its four-gun rear turret, German pilots quickly learned to attack the aircraft from head-on or below, where the guns could not bear. Consequently, the squadron suffered crippling losses over the Channel and Kent, leading to the Defiant's rapid and permanent withdrawal from the daylight fighting role.

25th August

Sunday the 25th August 1940, opened under a deceptive calm, but the late-summer stillness was a mere prelude to one of the most brutal and pivotal days of the battle.

After a five-day lull, the fighting resumed with a new fury, a direct consequence of a strategic shift by Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring.

His new directive called for massed, tightly coordinated bomber streams with heavy, close fighter escorts, designed to overwhelm Fighter Command in a single, decisive blow.

The day’s events would prove to be a merciless test of this new strategy, and a costly one for both sides.

...targeting the crucial RAF airfield at Warmwell...

At 16:00, the first and largest assault began. Over 200 German aircraft swept across the Channel toward the southwest, their formations targeting the crucial RAF airfield at Warmwell, along with key naval assets at Weymouth and Portland.

The raid was spearheaded by Junkers Ju 88s from II./KG 51 and II./KG 54, protected by a formidable screen of Bf 110s and Bf 109s from units like JG 2 and JG 53.

Fighter Command scrambled every available squadron from 10 and 11 Groups, including Spitfires from Nos. 152 and 609 Squadrons, and Hurricanes from Nos. 87 and 213 Squadrons.

...a grim toll...

The ensuing clash was ferocious and widespread, with losses mounting on both sides.

The RAF lost sixteen fighters, a grim toll that included Squadron Leader Cedric Williams, commander of No. 17 Squadron, whose Hurricane was shot down by a Bf 110.

The Luftwaffe also suffered significant losses, with Count Manfred Czernin of the RAF downing an incredible three Bf 110s in a single minute through a combination of head-on and rear attacks.

Despite the heroic defense, several Ju 88s broke through to bomb Warmwell, damaging hangars and buildings.

While the airfield remained serviceable, the raid proved the effectiveness of the new German tactics in pushing bombers through to their targets, albeit at a heavy price.

Pilot Officer Keith Gillman was killed on the 25th August 1940.

Count Manfred Czernin

Full name Graf Manfred Maria Edmund Ralph Beckett Czernin von und zu Chudenitz, was an Austrian‑born RAF fighter ace, made his name during the Battle of Britain. Flying Hurricanes with No. 17 Squadron, he developed a reputation for fast, decisive attacks.

On 25 August 1940 he intercepted a formation of Bf 110s and destroyed three in a single minute, a feat highlighted in his DFC citation.

By the end of 1940 he was firmly established as an emerging ace, later proving equally formidable in covert SOE operations across occupied Europe.

...exhausted British pilots...

Later that evening, a second major raid over Kent and the Thames Estuary was met with similar ferocity, as the exhausted British pilots were forced into action once more.

As darkness fell, the Luftwaffe launched widespread night attacks on industrial centers across the country.

Heinkel He 111s from KG 55 struck Bristol, while others bombed Birmingham and Coventry, causing widespread damage and casualties.

...the psychological shock was immense...

The most significant event of the day came when a formation of German bombers, off course for their intended target, accidentally dropped their bombs on East London.

This unintentional strike was the first widespread bombing raid on the capital. Winston Churchill’s immediate response was to order Bomber Command to retaliate against Berlin.

Although the physical damage to the German capital was slight, the psychological shock was immense.

This act of reprisal marked a pivotal shift in the Battle of Britain, transforming the conflict from a tactical air campaign against Fighter Command into a brutal, total war that would soon become known as the Blitz.

The battle for air supremacy over the Channel had been abandoned for a new, and terrifying, war on Britain's cities.

26th August

By late August, the Luftwaffe had become frustrated by Fighter Command's resilience, and Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring enforced a new, rigid tactical doctrine: large-scale, heavily escorted daylight raids.

This approach, which kept fighters tightly bound to bombers, was designed to guarantee that the bombers reached their targets, albeit at the cost of tactical flexibility.

On August 26, 1940, Luftflotte 2 put this new strategy to the test with three major daylight operations across southern England. The day's events were a brutal and costly ordeal for both air forces, pushing them to their breaking point.

...were also decimated...

The first major raid struck at mid-morning, with around 50 Dornier Do 17 bombers and up to 100 fighters attacking the Dover–Folkestone sector.

Fighter Command scrambled six squadrons to meet the threat, but the defence was costly. No. 616 Squadron was caught climbing into position and lost seven Spitfires in rapid succession, with two pilots killed.

The two-man Defiants of No. 264 Squadron were also decimated, losing three aircraft to the fighter escort, though their gunners claimed several bombers in return.

By 12:50, the raid had been broken up, with limited damage to ground targets.

British workers salvage Aluminum from wrecked German raiders shot down over England on the 26th August 1940. The Luftwaffe suffered significant losses during operations over southern England that day as part of Adlerangriff. Engaging heavily defended RAF airfields and convoys, German bombers and fighters faced determined resistance from Hawker Hurricanes and Supermarine Spitfires. Estimates indicate that the Luftwaffe lost around 20–25 aircraft, including both bombers and escort fighters, with additional planes damaged. These losses highlighted the growing effectiveness of RAF Fighter Command, particularly the use of radar and coordinated defensive tactics, and foreshadowed the attritional nature of the air campaign that would intensify in September 1940.

...the fierce combat...

The second assault was even larger, involving 78 Do 17s and over 120 fighters that crossed the Essex coast.

Ten RAF squadrons, including the Czechs of No. 310 Squadron and No. 1 (RCAF) Squadron, scrambled to intercept.

During the fierce combat, Flying Officer R. L. Edwards became the first Canadian fighter pilot killed in action, shot down by defensive fire from a Do 17.

Despite the heavy opposition, six bombers broke through to bomb RAF Debden, destroying a hangar and other buildings, killing six personnel, and damaging several aircraft on the ground.

...were forced to jettison their ordnance...

The final major daylight operation fell to Luftflotte 3, with around 50 Heinkel He 111s escorted by over 100 fighters attacking Portsmouth and Southampton.

Many of the bombers were forced to jettison their ordnance into the Channel before reaching their targets, but Portsmouth was still badly hit.

Bombs struck the dockyard, damaging naval vessels like the destroyer HMS Acheron and the HMS Bulldog, and setting fire to a gasworks.

Fort Cumberland in Portsmouth after the Luftwaffe raid on the city on the 26th August 1940 by 150 aircraft. Approaching the Isle of Wight, they were intercepted at 16,000 feet by eight squadrons of RAF Spitfires and Hurricanes. Cloudy weather and constant harassment by the RAF made target acquisition difficult, forcing many bombers to overshoot the city without releasing their bombs. Forbidden to return loaded, they jettisoned their payload, hitting Langstone Harbour and waste ground, though the Hilsea gas works was struck. A single bomber group hit Fort Cumberland, causing 14 casualties. The RAF's decisive intervention prevented mass casualties in the city. German records deemed the raid a total failure, with eight aircraft lost.

27th August

Wednesday, August 27, 1940, offered a brief respite from the massed battles, with poor weather and low cloud severely restricting Luftwaffe operations.

Nonetheless, a number of German reconnaissance flights were intercepted and shot down across the south coast, with Major Wolfgang Schellmann of JG 2 claiming a Spitfire off the Dorset coast.

While the skies were quiet, an important internal debate raged within Fighter Command as AVM Keith Park met with AVM Sholto Douglas to voice his objections to the "Big Wing" formation, highlighting critical tactical disagreements.

...a sharp increase in night operations...

As darkness fell, this new, terrifying phase of the battle continued.

The Luftwaffe launched a sharp increase in night operations, with the heaviest traffic heading toward Birmingham and Coventry.

Widespread bombing occurred across Bristol, Plymouth, and other industrial cities, causing serious damage to factories, dockyards, and residential areas.

The BSA Small Arms Works at Smallheath in Birmingham sustained serious damage.

On the home front, reports of parachute landings triggered false Home Guard alerts, a sign of the widespread fear and paranoia.

...a grim reflection of the war's reach...

The day was costly for both sides, but particularly for the civilians on the ground.

The RAF lost just 4 airmen and 7 aircraft, while the Luftwaffe lost 12 airmen and 11 aircraft, with many of the German losses occurring during the day's brief skirmishes.

However, total ground casualties from enemy action were recorded as 37 killed and 102 injured, a grim reflection of the war's reach even on a day of relative calm.